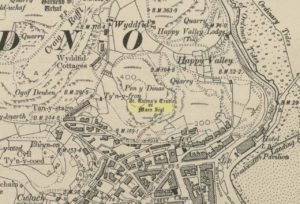

Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – NN 72110 47768

Also Known as:

-

Iron Well

Getting Here

From Fortingall village, head west and turn down into the incredible beauty that is Glen Lyon. As you enter the trees, a half-mile along you pass the small gorge of MacGregor’s Leap in the river below. 2-300 yards pass this, keep your eyes peeled for an old small overgrown walled structure on the left-hand side of the road, barely above the road itself. A large tree grows up above the tiny walled enclosure, within which are the unclear waters that trickle gently….

Archaeology & History

In previous centuries, this all-but-forgotten spring of water wasn’t just a medicinal spring, but was one of the countless sites where sympathetic magick was practised. The old Highlanders would have had a name for the spirit residing at these waters, but it seems to have been lost. The site is described in Alexander Stewart’s (1928) magnum opus on this stunning glen, where he wrote:

“Still a few yards more and Glenlyon’s famous mineral wishing well is seen gushing up, surrounded by its wall of rough stones now sadly in need of repair. It has a stone shelf to receive the offerings of those who still retain a trace of superstition or like to uphold old customs as they partake of its waters. The offerings usually consist of small pebbles, but occasionally something more valuable is found among them. The roadmen may clear that shelf as often as they like, but it is seldom empty for long.”

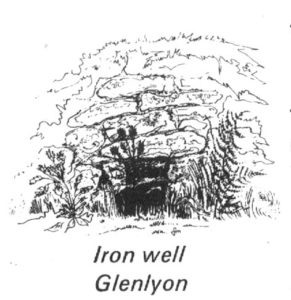

A local lady from Killin told us that she remembers the stone above the well still having offerings left on it 20-30 years ago. Hilary Wheater (1981) sketched it and called it the Iron Well.

The waters in this small roadside well-house actually emerge some 50 yards up the steep hillside (recently deforested) and in parts have that distinct oily surface that typifies chalybeates, or iron-bearing springs – which this site is an example of. Its medicinal properties would help to people with anaemia; to heal women just after childbirth; to aid those who’d been injured and lost blood; as well as to fortify the blood and stimulate the system.

Across the road from the well, Stewart (1928) told of a giant lime tree that was long known to be the meeting place for lovers (perhaps relating to the well?), and the name of the River Lyon here is the Poll-a-Chlaidheamh, or ‘the pool of the sword’, whose history and folklore fell prey to the ethnic cleansing of the english.

References:

- Stewart, Alexander, A Highland Parish, Alexander Maclaren: Glasgow 1928.

- Wheater, Hilary, Aberfeldy to Glenlyon, Appin Publications: Aberfeldy 1981.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian