Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 26777 48952

Also Known as:

- Ormscliffe Crags

This is an outstanding site visible for miles around in just about every direction – so getting here is easy! If you’re coming from Harrogate, south down the A658, turn right and go thru North Rigton. Ask a local. If you’re coming north up the A658 from the Leeds or Bradford area, do exactly the same! (either way, you’ll see the crags rising up from some distance away) As you walk to the main crags, instead of going to the huge central mass, you need to follow the line of walling down (south) to the extended cluster of much lower sloping rocks. Look around and you’ll find it!

Archaeology & History

On the evening of May 27, 2024, I received a phone call from a Mr James Elkington of Otley. He was up Almscliffe Crags and the wind was howling away in the background, taking his words away half the time, breaking the sentences into piecemeal fragments. But through it all came a simple clarity: as the sun was setting and the low light cut across the rocky surface, a previously unrecorded cup-and-ring design emerged from the stone and was brought to the attention of he and his compatriot Mackenzie Erichs. All previous explorations for rock art here over the last 150 years had proved fruitless—until now!

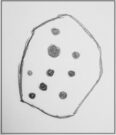

On the east-facing slope of the stone, just below the curvaceous wind-and-rain hewn shapes at the very top of the boulder, is a singular archetypal cup-and-ring. It’s faint, as the photos show, but it’s definitely there. What might be another cup-and-ring is visible slightly higher up the sloping face, but the site needs looking at again when lighting conditions are just right! (you can just about make it out in one of the photos) But, at long last, this giant legend-infested mass of Almscliffe has its prehistoric animistic fingerprint, bearing fruit and giving watch to the countless heathen activities going back centuries. Rombald’s wife Herself might have been the mythic artist of this very carving! (if you want to read about the many legends attached to the major Almscliffe rock outcrop, check out the main entry for Almscliffe Crags)

References:

- Bennett, Paul, “Almscliffe Crags, North Rigton,” Northern Antiquarian 2010.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian