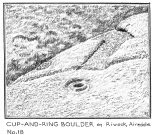

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 07905 47268

For those who like a walk: take the route to reach the Swastika Stone and keep walking west along the Millenium Way footpath, past the Piper’s Stone carving and over the next two walls. Then, stagger down the steep hill and head for the large upright near-cuboid block of stone and, once here, walk 30 yards to your east! Alternatively, from the Silsden-side, go along Brown Bank Lane up and past Brown Bank caravan park, and at the second crossroads turn right and travel for exactly 1¼ miles (2km) along Straight Lane (from hereon there’s nowhere to park!) which runs naturally into Moorside Lane, and notice the raised gate entrance into the field on your right. Walk to the top of this field, go through the next gate and, less than 100 yards uphill (south) you’ll find the stone in question.

Archaeology & History

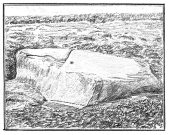

Rediscovered by Paul Bowers in 2011, this is another one of those petroglyphs that’s difficult to make out unless the light is falling just right across the surface of the stone. Two distinct cup-marks can be seen near the more southern-edge of the stone, one of which has a near-complete, albeit unfinished ring around it, and from this a seemingly carved line runs roughly parallel with the edge of the stone, down towards another equally distinct cup close to the southwestern edge of the rock. Most of the stone is nicely covered in a decent lichen cover, so the design’s a bit difficult to see when the light’s not right. But, if you’ve made it this far, the petroglyph 30 yards to the west will make up for any disappointment may have!

References:

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding Supplement, 2018.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian