Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 00076 50540

Getting Here

From near Skipton town centre, at the Cross Keys Inn along Otley Road, go up Short Bank Road all the way to the very top and then into the trees onto the Dales High Way footpath. Walk up for literally ¼-mile (0.4km) and where the path bends and heads ENE, notice here a footpath that takes you over the wall. Once on the other side, the path splits with one heading SE and the other roughly alongside the walling to the SW, which is where you need to go. About 200 yard on, go through the gate into the field and then another 375 yards on you’re into another field (copse of trees in front of you). Just as you’ve gone into this field, walk immediately left, uphill, by the walling for about 100 yards, over the marshy dip, then head into the field where, about 75 yards in, you’ll see some rocks scattered about…

Archaeology & History

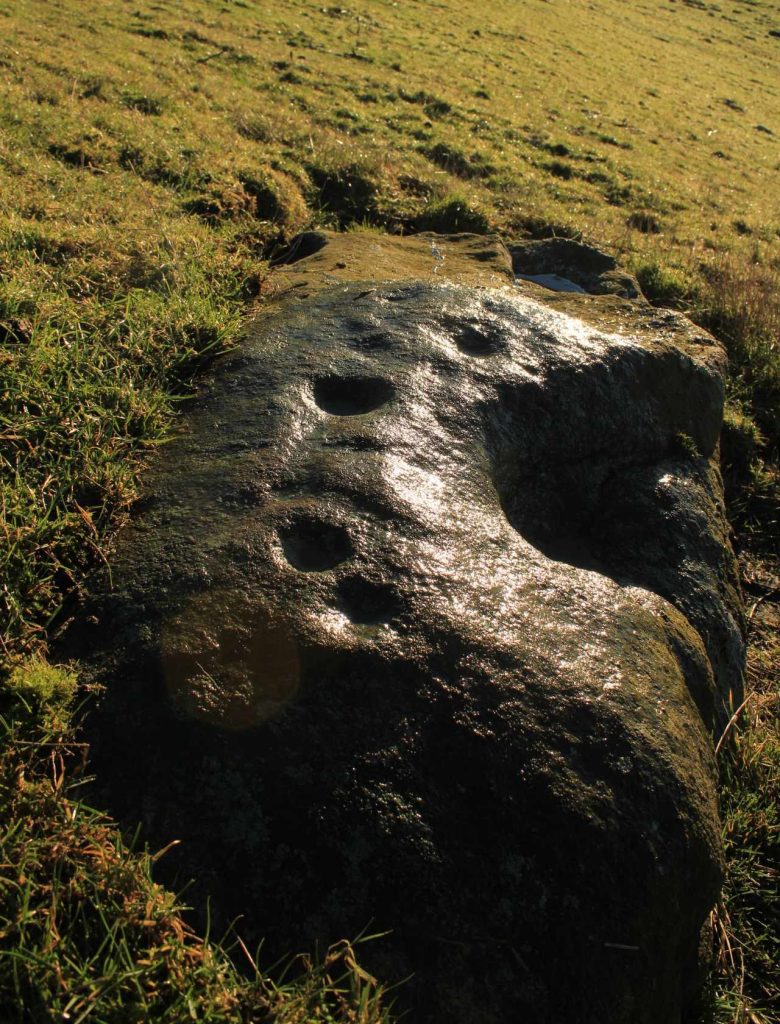

In an area that’s had some considerable quarrying done to it, we’re lucky to find that this carving still exists. It was rediscovered by Thomas Cleland (hence its name!) in the summer of 2024. It consists of four distinct cups, with a possible fifth (and maybe more?) on its smooth elongated surface. The cups, as we can see, are quite deep and unmistakable. An incomplete ring seems to be around at least one of the cups; and there seems to be a carved straight line running between another two of them. A simple but distinct design and in a lovely setting gazing cross the Airedale valley from here.

There are very few other carvings in this neck o’ the woods (the Great Laithe Wood carving aint too far away), but the fact that this has been found would suggest that others are probably hiding away in the undergrowth. Check out the Iron Age Horse Close Hill enclosure while you’re up here too.

Acknowledgements: A huge thanks to Thomas Cleland, not only for finding the carving, but also for allowing use of his photos in this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.