Earthworks: OS Grid Reference – SE 0680 3808

Also Known as:

- Blood Dykes

Getting Here

Various ways here. From Keighley, go up the Halifax Road, first left after the Ingrow West train station, uphill, then up the long zizaggy road till you hit the pub at the crossroads. Park up and walk along the road in front of the pub for 1-200 yards and look at the hill above you! Alternatively, from Bingley go up to Harden on the B6429 and literally just where the village ends, there’s a small right-turn (if you’re going past the fields on either side, you’ve just missed the turning!). Go up there till the road reaches the top and stop! Catstones Hill is in the heather over the wall on your left!

Archaeology & History

A somewhat anomalous earthwork site, with lots of archaeohistorical speculation behind it, but no firm conclusion as to its precise nature as yet. Defined variously as an earthwork, an enclosure (for both people and cattle!) and a settlement by respective archaeologists over the years, there is little to be seen of the place on the ground and it doesn’t tend to bring raptures of delight to the common antiquarian. When William Keighley (1858) described this place, Catstones Ring was,

“enclosed on three sides by a considerable bank of earth, and bears evident marks of the plough. The country people believe it to have been an intrenchment or camp.”

Mrs Ella Armitage (1905) thought this site may have been “a prehistoric fort,” but said little more about it. In the same year however, Mr Butler Wood (1905) gave us a much better account of the place, describing Catstones Ring as “the most striking earthwork in the neighbourhood of Bradford.” His broader description told that:

“It encloses the crest and slope of a hill, and measures 266 yards on the east side (which is perfect), and 100 yards on the north side; the latter, however, being traceable at least 100 yards further across cultivated fields. The south side is almost obliterated by quarries, while the western portion has disappeared altogether. The fosse which surrounded this fine fortification is still visible on the eastern side.”

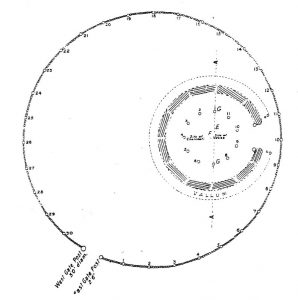

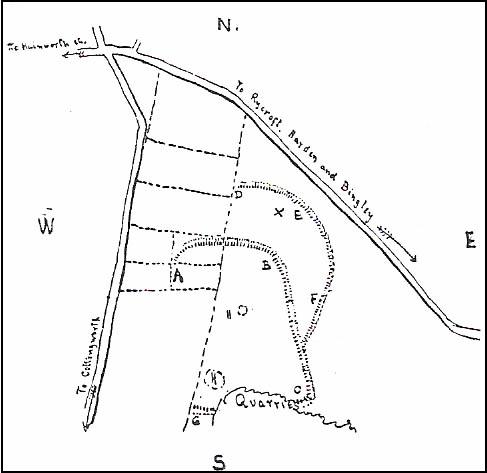

A couple of years later two short notes were made of the site in Forshaw’s Yorkshire Notes and Queries. Peter Craik (1907) of Keighley described the dimensions of the main ring as being “110 x 320 yards (rough guess),” and he also described finding the remains of a cairn in the outer dyke section (marked as ‘X’ on Craik’s diagram, below). On the nature of the site, he wrote:

“Catstones would appear to have been built as a defence against invasion from the south, for in contrast to the early defensible approach from that direction is the fact that to the north lies the undulating expanse of Harden Moor, which for the most part is on a level with the ring, even the highest point in the immediate vicinity being without the main circle, though enclosed in a minor outwork. The large extent of the ring makes it rather difficult to believe that enough men could be collected in the immediate neighbourhood to man the lines satisfactorily; and again as a shelter for cattle, etc, in time of war it does not appear to be well designed, for most of the interior would be commanded within easy range of arrows. Certain old excavations exist within the ring; probably they were made in search of gravel or some such material, but is this conjecture certain? Can they possibly mark the site of dwellings?”

J.J. Brigg (1907) followed up Craik’s short piece with the suggestion that the site was Roman in origin, saying:

“In showing the 6in map to Professor Bosanquet of Liverpool…he said there was no reason why it should not be Roman, merely because there is no masonry. The Roman legions went into laager* every night, and it is quite possible that some very large body of soldiers halting there for the night might have thrown up an earthwork and planted thereon the stakes which they always carried with them for that purpose.”

But I think this is most unlikely. Very little has been found here to give us a better idea of dates and function; and in a limited excavation here in 1962, no artifacts of any kind were located. A little more recently, J.J. Keighley (1981) has suggested the site to be Iron Age in date, describing it as one of the most impressive sites of its kind in the region. The Catstones Ring is “a 6.5 hectare quadrangular ditched enclosure,” he wrote, which he thought had been much destroyed by the adjacent quarrying.

“Aerial photographs taken by the County Archaeology Unit in 1977 however, shows that the southeastern corner of the enclosure and parts of its southern ditch survived the quarrying. Villy (1921) observed an outwork to the north of the main enclosure, which was visible on aerial photographs taken in 1948, and the 1977 aerial photographs…show a possible annexe attached to the outside of the northeastern corner of the main enclosure.”

This extended section of Catstones’ main earthworks were, in fact, first described in the article by Peter Craik (1907), as shown in the hand-drawn plan of the site here. And in all honesty, virtually nowt’s been done since these early antiquarians diggings and essays. The information from the present day Sites and Monuments Record says that the site is a “late prehistoric enclosed settlement” and that quarrying has destroyed much of the west side.

Folklore

Harry Speight (1892) reported the earthworks here to have been a site where a great battle once took place, between the local people and the early Scottish tribes.

References:

- Armitage, E., ‘The Non-Sepulchral Earthworks of Yorkshire,’ in Bradford Antiquary, New Series 2, 1905.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Brigg, John J., “Catstones Ring,” in C.F. Forshaw’s Yorkshire Notes & Queries, volume 3 (H.C. Derwent: Bradford 1907).

- Craik, Peter, “Catstones Ring,” in C.F. Forshaw’s Yorkshire Notes & Queries, volume 3 (H.C. Derwent: Bradford 1907).

- Keighley, J.J., “The Prehistoric Period,” in Faull & Moorhouse’s, West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey to AD 1500 (WYMCC: Wakefield 1981).

- Keighley, William, Keighley, Past and Present, R. Aked: Keighley 1858.

- Speight, Harry, Chronicles and Stories of Old Bingley, Elliott Stock: London 1892.

- Villy, Francis, Some Intrenchments of Large Size in the Keighley District, Keighley 1908.

- Villy, Francis, “The Slag-Heaps of Harden,” in Bradford Antiquary, volume 6, 1921.

- Wood, Butler, ‘Pre-Historic Antiquities of the Bradford District,’ in Bradford Antiquary, New Series 2, 1905.

* a formation of armoured vehicles used for quick resupply or refueling.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian