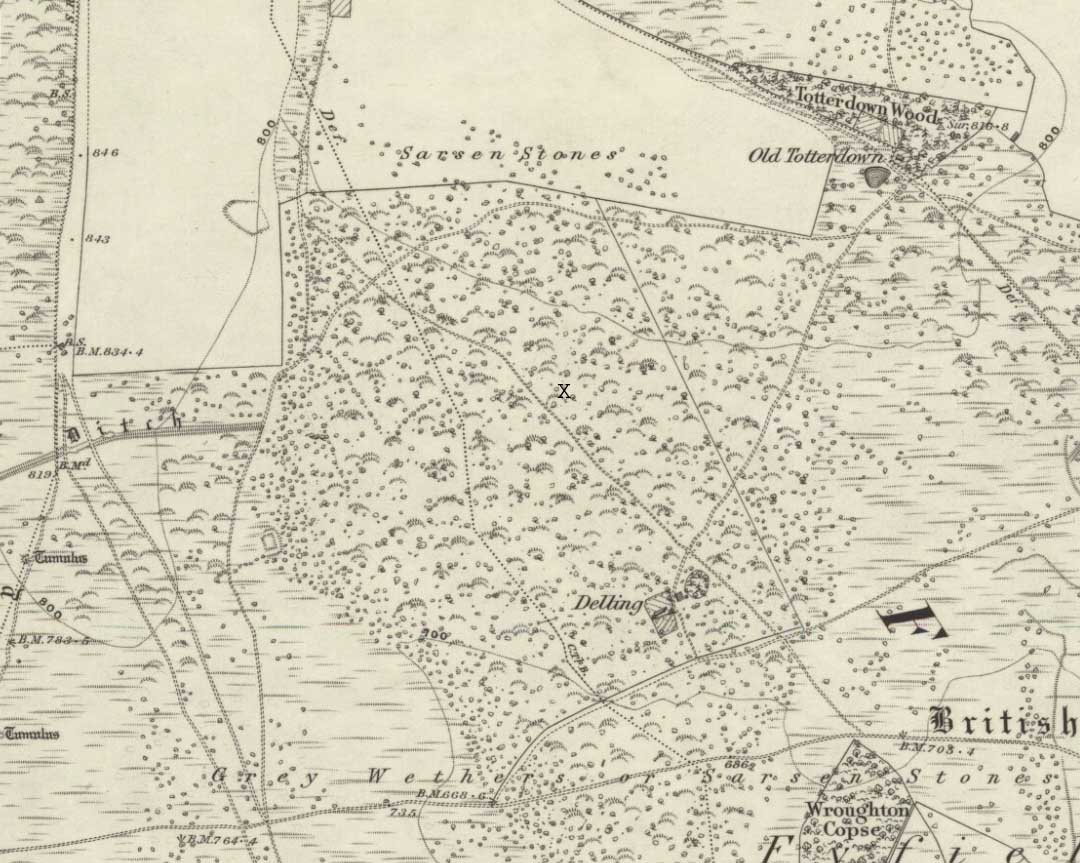

Stone Circle (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SU 0986 6713

Archaeology & History

This all-but-destroyed megalithic ring is all-but-unknown in most of the archaeological gazetteers — including even Burl’s (2000) magnum opus! But we know it was there. And according to the Avebury authority Pete Glastonbury , there “are a couple or three small stones buried on the hill but nothing else to see.” Which is a pity, as the site sounds like it was something to behold in bygone times. Although it seems to have been described initially by the legendary druidical antiquarian, William Stukeley, a more lengthy description followed in the 19th century by the reverend A.C. Smith (1885), when he and a friend took it upon themselves to cut back some of the turf that was covering a number of stones — and they weren’t to be disappointed!

The site itself appears to have stood right on the southern boundary line of Avebury parish, meaning that the site could have been named and cited on any early boundary perambulation records that might exist of the parish. (do any of you Wiltshire folk have access to any such old records?) But if there are no such early accounts, the earliest record we’ll have to stick with is good old Mr Stukeley (1743), who only gave it a passing mention, saying:

“Upon the heath south of Silbury was a very large oblong work like a long barrow, made only of stones pitch’d in the ground; no tumulus. Mr Smith before-mentioned told me his cousin took the stones away (then) fourteen years ago, to make mere (boundary, PB) stones withal. I take it to have been an Archdruid’s, tho’ humble, yet magnificent; being 350 feet or 200 cubits long.”

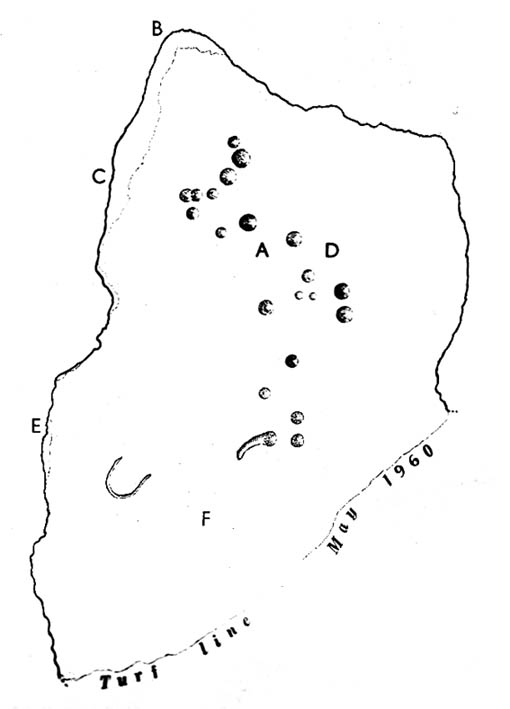

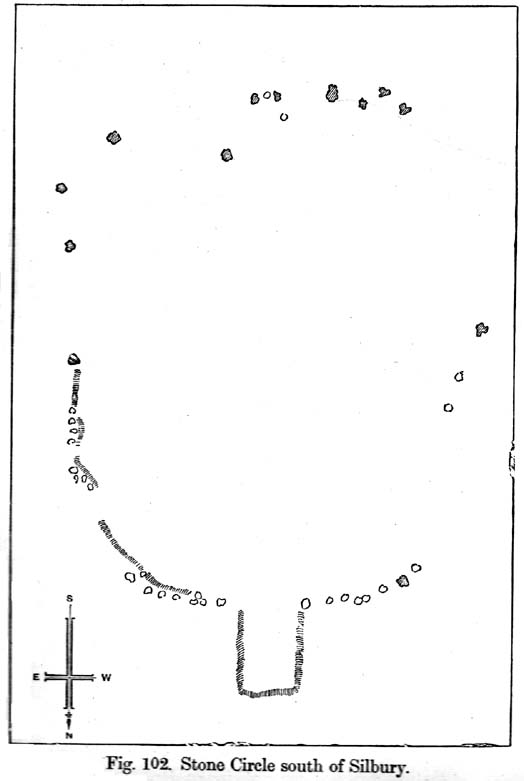

Nearly 150 years later Reverend Smith gave us a more detailed account, and ground-plan, describing the place as,

“a stone circle, of considerable dimensions, though imperfect and formed of very small sarsens, but which I believe to have been in some way connected with Abury. Though it appears to have been mentioned by Stukeley one hundred and fifty years ago, it had been long since buried, and completely forgotten till I was fortunate enough to discover it by digging in the year 1877. I was led to the discovery by the suspicious look of certain stones which, though scattered in no regular form, appeared as if they might have once stood erect, in some sort of order, on the segment of a large circle. I had often stopped to examine them as I wandered over that part of the downs; till at last previous suspicions ripened into conviction, as closer observation revealed sundry other stones just showing above the ground, and there also seemed to be faint indications of a trench, all pointing, with more or less accuracy, to the supposed circle. Not to dwell upon the details of the investigation, which, however, were of singular interest to me, the result was that (with the permission of both owner and occupier of the land, and assisted by Mr William Long), I probed the ground in every direction, and uncovered the turf wherever a stone was found: and on our first day’s work we unearthed no less than twenty-two sarsen stones, all forming part of the circle, and lying from two to twelve inches below the surface. These stones were all of small size, some of them very small, but that they were placed by the hand of man in the positions they now occupy, in many cases nearly touching one another, and that they formed part of a large circle or oblong, admits, I think, of no doubt. I say part of a circle, because, though the northern, southern and eastern segments are tolerably well defined, I could find scarcely a single stone on what should be the western segment to complete the circle. That the area thus enclosed is not insignificant will appear from the diameter (in length, or from north to south, 261 feet; and in breadth, or from east to west, 216 feet). Again, its position (due south of Silbury, and within full view of it, as well as the Sanctuary on Overton Hill, and with Abury immediately behind Silbury, due north of it, from which also Silbury is equidistant) seems to intimate that it may have had some connection with the great temple.”

Smith then proceeded to query the nature of the monument, commenting on how Sir John Lubbock and members of the British Archaeological Association were intrigued by the remains, but a little perplexed and unable “to form any opinion” as to the exact nature of the site. But this didn’t stop mythographer and historian Michael Dames (1977) who, in his classic Avebury Cycle, suggested that the site “marked the navel of the landscape goddess” in the region.

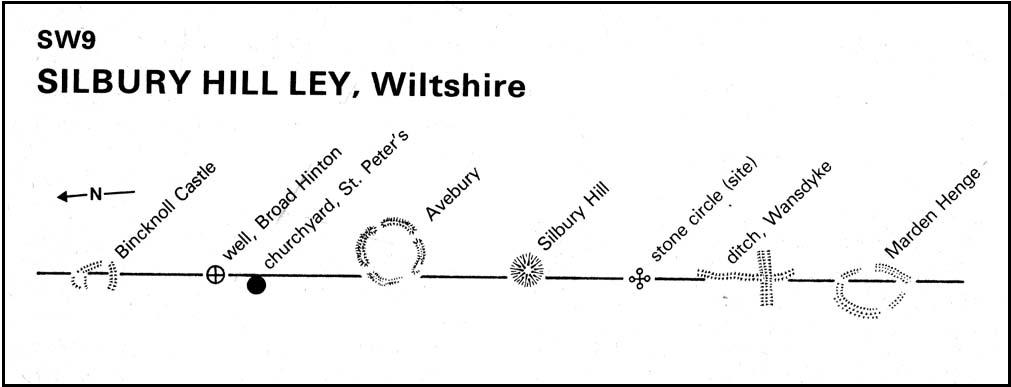

The site didn’t go unnoticed in Devereux and Thomson’s (1979) classic Ley Hunter’s Companion, where it plays an important point along a ley that runs north-south for 13 miles between Bincknoll Castle at the north, to Marden Henge at the south. Such an alignment had been noted much earlier by other archaeologists and historians.

The site does look strange for a stone circle in Smith’s ground-plan and has more the hallmarks of a type of enclosure or settlement of some sort. It certainly wouldn’t be out of place, design-wise, as a prehistoric settlement in our more northern climes. However, without further data it seems we may never know the true nature of this old stone site…

References:

- Dames, Michael, The Avebury Cycle, Thames & Hudson: London 1977.

- Devereux, Paul & Thomson, Ian, The Ley Hunter’s Companion, Thames & Hudson: London 1979.

- Glastonbury, Pete, “Silbury ‘stone circle’ Query,” private comm., March 6, 2011.

- Smith, A.C., A Guide to the British and Roman Antiquities of the North Wiltshire Downs, Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society 1885.

- Stukeley, William, Abury, A Temple of the British Druids, W. Innys & R. Manby: London 1743.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian