Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 15078 43546

On the moorland road from Dick Hudson’s pub, head east along the Otley Road for more than 1½ miles, past the T-junction right-turn at Intake Gate (to Hawksworth) and just a quarter-mile further on park-up at the roadside (opposite Reva Reservoir). Walk (north) thru the gate into the field and after 300 yards through another gate into the next field. From this gate, walk straight north to the Fraggle Rock cup-and-ring stone, then go down the slope NNW for nearly 50 yards and just above the old track you’ll see the edge of this stone peeking out!

Archaeology & History

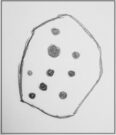

One of a number of previously unrecorded carvings in these fields, this is a pretty simplistic but unique design. The first thing you’ll notice is at the top-corner of the stone where, like many rocks on these moors, a nicely-worn cup stands out. Erosion obviously…. or so it first seems. This cup-mark has another two by its side, along the top edge of the stone which, again, initially suggested them to be little more than natural. But in rolling back the turf this assumption turns out to be wrong; for, along the west-side of the rock you’ll see a notable pecked groove running down to another cup-mark about twelve inches below, kinking slightly just before it reaches that cup. You can see this in the photo. Now, if we return to the prominent cup-mark at the top corner of the stone, in certain light there seems to be a very faint incomplete ring around it – but we can’t say for certain and it needs to be looked at again in better light.

The name given to this carving (thanks to Collette Walsh) comes from the wavy lines that go into the middle of the stone from the long pecked line. These wavy lines are natural, although one portion of them might have been artificially enhanced. It’s difficult to tell one way or the other and we’ll have to wait for the computer boys to assess this particular ingredient. Just above these “waves” is a single eroded cup-mark nearly 2-inch across. And that’s that!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian