Holy Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 89801 86524

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 46862

- Lady’s Well

- Spaw Well

Archaeology & History

Site of the Lady Well, Airth

Once to be seen flowing on the south-side of the Pow Burn below Airth Castle, all traces of this once sacred site has fallen prey to the usual advance of the so-called ‘civilized’. In literary terms, the site was first described in church records from 1657—as Ladieswell—and the accounts we have of the place from then are most revealing in describing the traditional use of the place by local people. It was a sacred site, obviously, chastised by the madness of the christian regime of the period, in their attempt to destroy indigenous customs and societal norms. William Hone (1837) gave an extended account of what some people were up to here in his Everyday Book:

“In 1657, a mob of parishioners were summoned to the session, for believing in the powers of the well of Airth, a village about six miles north of Falkirk, on the banks of the Forth, and the whole were sentenced to be publicly rebuked for the sin. –

“”Feb. 3, 1757, Session convenit. Compeared Bessie Thomson, who declairit scho went to the well at Airth, and that schoe left money thairat, and after the can was fillat with water, they keepit it from touching the ground till they cam horm.”

“”Ffebruary 24. — Compeired Robert Fuird who declared he went to the well of Airth, and spoke nothing als he went, and that Margrat Walker went with him, and schoe said ye beleif about the well, and left money and ane napkin at the well, and all was done at her injunction.”

“”Compeared Bessie Thomson declarit schoe fetch it horn water from the said well and luit it not touch the ground in homcoming, spoke not as sha went, said the beleif at it, left money and ane nap-kin thair; and all was done at Margrat Walker’s command.”

“”Compeired Margrat Walker who denyit yat scho was at yat well befoir and yat scho gave any directions ”

“”March 10. Compeared Margrat Forsyth being demand it if scho went to the well of Airth, to fetch water thairfrom, spok not by ye waye, luit it not touch ye ground in homcoming? if scho said ye belief? left money and ane napkin at it? Answered affirmatively in every poynt, and yat Nans Brugh directit yem, and yat they had bread at ye well, with them, and yat Nans Burg said shoe wald not be affrayit to goe to yat well at midnight hir alon.”

“”Compeired Nans Burg, denyit yat ever scho had bein at yat well befoir.”

“”Compeired Robert Squir confest he went to yat well at Airth, fetchit hom water untouching ye ground, left money and said ye beleif at it.”

“”March 17. Compeired Robert Cochran, declairit, he went to the well at Airth and ane other well, bot did neither say ye beleif, nor leave money.”

“”Compeired Grissal Hutchin, declairit scho commandit the lasses yat went to yat well, say ye beleif, but dischargit hir dochter.”

“”March 21. Compeired Robert Ffuird who declairit yat Margrat Walker went to ye well of Airth to fetch water to Robert Cowie, and when schoe com thair, scho laid down money in Gods name, and ane napkin in Robert Cowie’s name.”

“”Compeired Jonet Robison who declairit yat when scho was seik, Jean Mathieson com to hir and told hir, that the water of the well of Airth was guid for seik people, and yat the said Jean hir guid sister desyrit hir fetch sum of it to hir guid man as he was seik, bot sho durst never tell him.”

“”These people were all 44 publicly admonishit for superstitious carriage.””

The practices continued. In 1723, a Mr Johnstoun of Kirkland, writing about the parish of Airth, also told of the reputation of the well, saying,

“Upon the south side of the Pow of Airth, upon its very edge, is a spaw well famous in old times for severall cures, and at this day severalls gets good by it, either by drinking or bathing. Its commonly called by the name of Ladies well. Its about two pair of butts below Abbytown bridge.”

The fact that he told us it was “good for bathing” suggests a pool was adjacent, or at least the tiny tributary between it and the Pow Burn gave room for bathing and had a curative reputation. (there are many pools in the Scottish mountains with this repute – some are still used to this day!)

It was then described by Robert Ure in the first Statistical Account of 1792, where he told how the people were still using the waters, despite the crazy early attempts to stop them. “There is a Well, near Abbeytown Bridge,” he told,

“called Lady-Well, which is thought to be medicinal. Numbers have used it, and still use it as such. It is supposed to have obtained that name, from the holy water, in the time of Popery, being taken from it, to supply the abbacy, or Catholic Church, then at Airth.”

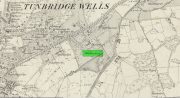

Lady Well on 1865 map

But we know that its origins as a celebrated well pre-date any christian overlay. People were reported visiting the site from as far away as Edinburgh, such was its repute!

Much later when the Ordnance Survey lads came here, showing it on their first map of Airth, they made their own notes of the place, saying briefly,

“A small well close to the Pow Burn – it is supposed to have derived its name from the Custom of dedicating wells to the Virgin Mary – so Common prior to the Reformation. It is not a mineral well.”

Ugly plastic pipe is all that remains

But its demise was coming. In the wake of the christian Industrialists and their myth, subsuming the necessary integral sacrality of the Earth, the waters of the well were eventually covered. When the Royal Commission (1963) lads gave the site their attention in October 1954, they reported that “no structural remains” of any form could be seen here, and in recent years all trace of the well has vanished completely. When we visited the site a few months ago, perhaps the very last remnant of it was a small plastic pipe sticking out of the muddy bankside, dripping dirty water into the equally dirty Pow Burn.

It would be good if local people could at least put a plaque hereby to remind people of the history and heritage that was once so integral to the way they lived their lives.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Stirling, TNA 2018.

- Fraser, Alexander, Northern Folk-lore on Wells and Water, Advertiser Office: Invermess 1878.

- Frost, Thomas, “Saints and Holy Wells,” in Bygone Church Life in Scotland (W. Andrews: Hull 1899).

- Hone, William, The Every-day Book – volume 2, Thomas Tegg: London 1837.

- MacFarlane, Walter, Geographical Collections Relating to Scotland – volume 1, Edinburgh Universoty Press 1906.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Murray, G.L., Records of Falkirk Parish – volume 1, Duncan & Murray, Falkirk 1887.

- Reid, John, The Place-Names of Falkirk and East Stirlingshire, Falkirk Local History Society 2009.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – volume 2, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian