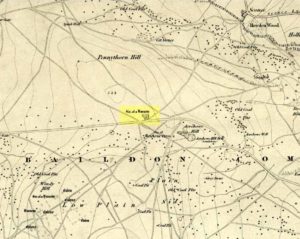

Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – SE 0501 4949

Also Known as:

- Parson’s Lane Tumulus

From Silsden go up the long hill (A6034) towards Addingham until the hill levels out, then turn left on Cringles Lane (keep your eyes peeled!) for about 500 yards until you reach the Millenium Way footpath, or rather, green lane track, to your right. Walk along this usually boggy old road for another 400 yards until you’re level with the small copse of trees below the field (about 100 yards away). The slightly raised ditched mound on the left side of the track ahead of you is what you’re after!

Archaeology & History

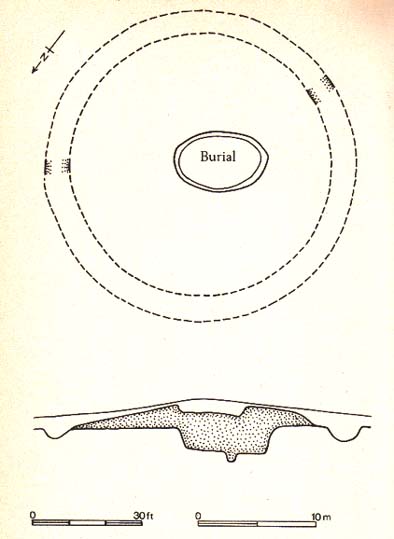

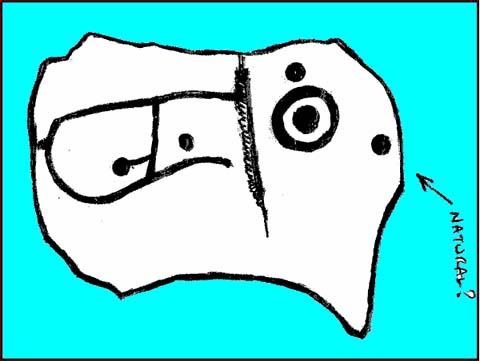

Unless this old tomb was pointed out, you probably wouldn’t give the place a second glance. It’s a seemingly isolated singular round tomb, subsided on top and surrounded by a small ditch, running into the edge of the walling. Gorse bushes and a few rocks are around the edges of the site. Harry Speight (1900) described this old tomb as a

“lonely isolated mound, to be seen in Parson Lane about a hundred yards west of the Celtic boundary, Black Beck, where some old dying chief has called his friends around him bidding them, “heap the stones of his renown that they may speak to other years.” It is a tumulus 80 feet in circumference and does not seem to have been disturbed.”

In Faull and Moorhouse’s (1981) magnum opus they describe the site as “the denuded remains of a ditched round barrow,” but say little else. It may have had some relationship with the settlement remains in and around the huge Counter Hill complex, immediately north.

References:

- Cowling, E.T., Rombald’s Way: A Prehistory of Mid-Wharfedale, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Faull, M.L. & Moorhouse, S.A. (eds.), West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Guide to AD 1500 (4 volumes), WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian