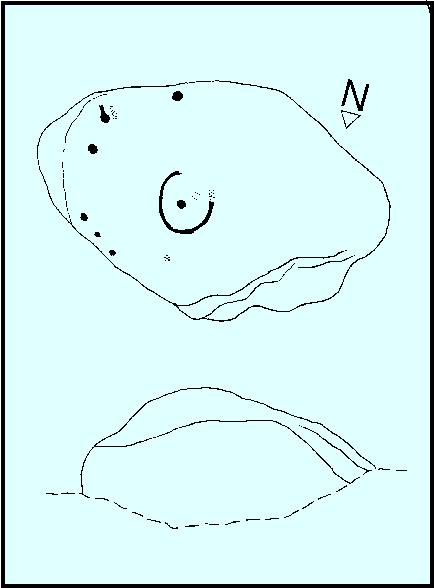

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 15774 41191

You can take the same directions to get here is you follow the route for the Hawksworth Spring (01) carving, or take this alternative route. Take the standard road from Guiseley along Hawksworth Road. When you reach the first row of old houses in the village, a couple of hundred yards on you reach the village school and, shortly after the footpath is sign-posted. Walk left (downhill) through the field for half-a-mile until you reach the woods. 100 yards into the into the trees, walk to your right and follow the line of walling straight for 400 yards, then veering right up the slope and it then slowly bends round, keeping to the wallside all along. It then starts heading back downhill. As it does so, 10 yards from the wall into the woods you’ll see the broken triangular rock of the Hawksworth Spring (01) carving. Walk another 10 yards where the large holly bushes are and you’ll see the large sloping stone in front of you.

Archaeology & History

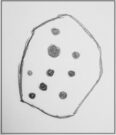

This carving is similar in nature to its companion 10 yards away, inasmuch as each of them possess two small arcs of cup-marks almost in the same format, very close together, one above the other near the top of the stone. It’s possible that the mythic nature/function of this particular element of arcs is the same on each stone—although fuck knows what it might be!

Below this double arc (only one of which is clearly visible in the photos) we see a scatter of other cup-marks—perhaps six, perhaps seven—one of which appears to have a very faint incomplete ring round it. When Liz Sykes and I visited the place, the light of day and the shadows across the rock didn’t help to convince us one way or the other, so we await news from other visitors who get better light conditions to tell us whether our hopeful eyes were deceiving us or not. There are a number of other marks on its surface, but these are much more recent and very obviously cut, or rather scratched, by metal artifacts with no bearing on the prehistoric design.

References:

- Boughey, K.J.S. and Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock of the West Riding (Supplement), Shipley 2018.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Liz Sykes for her renowned cleaning skills!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian