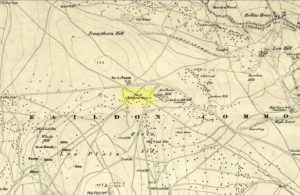

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 15073 40440

Also Known as:

- Carving no.50 (Hedges)

- Carving no.194 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Getting Here

Take the road up through Baildon village, across at the roundabout up Northgate and up onto the moor, then after a few hundred yards turn left on the Bingley Road. About five hundred yards along, keep your eyes peeled for where the ruined reservoirs are to the left-side of the road. Straight across the road from here (north) you’ll see the small cliffs of Eaves Crag. Walk along the footpath that runs above the cliffs and, about 80 yards past them, keep your eyes peeled on the ground right in the middle of the path. You can’t really miss it!

Archaeology & History

First mentioned in passing in the magnum opus of W. Paley Baildon (1913) and subsequently in one of Sidney Jackson’s (1955) series of profiles on the Baildon Moor carvings, this all but insignificant carving comprises of a simple cup-and-half-ring and another singular cup-mark a little further along the stone. John Hedges (1986) described this carving as being a “well marked cup surrounded by horseshoe groove – also well marked. Possible small cup and incomplete ring.” Whilst the minimalists Boughey & Vickerman (2003) told it to be simply, “two cups, one with incomplete ring.” A peculiarity with this design is that it might have been cut by a metal implement, perhaps in the Bronze Age, perhaps even in the Iron Age. We might never know…

References:

- Baildon, W. Paley, Baildon and the Baildons – volume 1, St. Catherines: Adelphi 1913.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks of Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Jackson, Sidney, ‘Cup and Ring Boulders of Baildon Moor,’ in Bradford’s Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 1:10, 1955.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian