Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 07450 46658

Also Known as:

- Carving no.230 (Hedges)

- Carving no.56 (Boughey & Vickerman)

The easiest way to get reach here is via the Doubler Stones, which is usually approached either from the long and winding country lanes Silsden-side (you can’t drive all the way and there are hardly any parking spots en route), or from a long walk over the moors. Taking the latter route, probably the easiest is by starting at Whetstone Gate right on the moortop, on the Ilkley-Keighley road. From here, walk west along the footpath by the wallside for more than ½-mile until you reach the West Buckstones. From here, take the footpath NW (not SW) alongside the walling for literally one mile, where a notable angular skewing of three walls appears: keep to the left and walk alongside that wall for another ⅓-mile (0.5km) then climb over the wall and head straight for the small TV mast. The Giant’s Chair’s just below it.

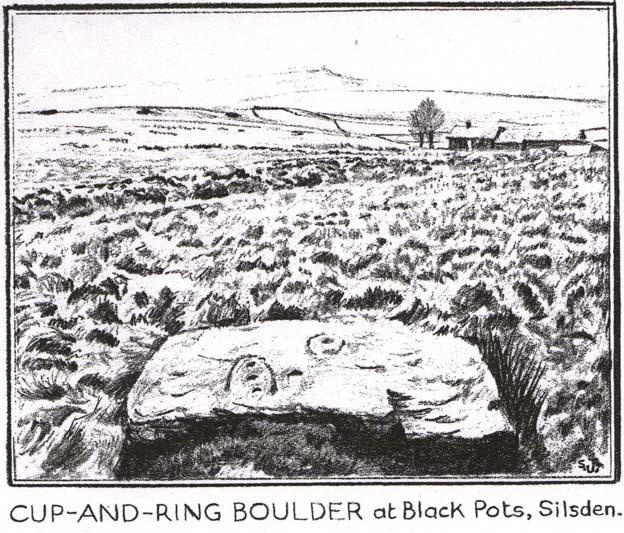

Archaeology & History

Some time in the mid- to late-1970s, on one of our early ventures to see the legendary Doubler Stones, this great rock outcrop of the Giant’s Chair also, understandably, drew our attention. And, as young fertile teenage lads, we all but flew up onto the top of this great rocky rise with relative ease. Now, nearly fifty years later, I’m unable to climb onto its top without ropes. (sigh….) It’s not easy. Anyhow, when we were on top of this rock as kids, a number of notable cup-markings stood out to us—in no distinct order, as I recall. But on the day of our clambering visit, She was grey and overcast; as She was on the two or three other visits we made to the stone, sitting on its top, fondling the cup-marks and eating our sarnies. All that I ever noticed were the cup-markings.

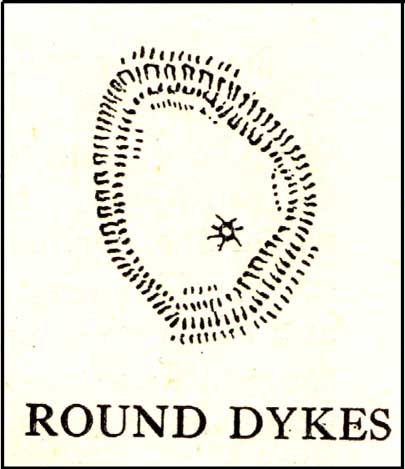

A few years after my early visits here, John Hedges (1986) wrote about this “very large high rock.” He mentioneed the cup-markings, obviously, but he also mentioned some things that we’d missed, saying that here are,

“Six large shallow worn cups, one with (a) partial ring and another with possible ring. One cup on SW end.”

Sadly, I’ve never seen these rings and, these days, my ageing bones might not allow me back onto its surface to see them. (the expression, “sad bastard” comes to mind!) On a recent visit here with Sarah Walker of Silsden, neither of us could get our useless arses on top! (the photos taken here were done with me stood on top of an adjacent rock, hands held high, trying to get at least some elements of the carving—with a minor bit of success, I think) I take comfort in the fact that when Boughey & Vickerman (2003) subsequently added this carving in their enlarged inventory, that they never got to see them either, as they gave it the completely wrong grid-reference! And so, due to the ineptitude of us old folk, I await some younger and more competent explorers who can climb up on top and send us some good photos of the design, when weather and lighting conditions allow for good imagery. Are there any takers…?

References:

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Deacon, Vivien, The Rock Art Landscapes of Rombalds Moor, West Yorkshire, ArchaeoPress: Oxford 2020.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks to Sarah Walker for helping, albeit unsuccessfully, to scale this old rock to see the cup-and-rings on my last visit here. At least we tried…

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.