Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 07507 44564

Also Known as:

- Carving no.26 (Hedges)

- Carving no.65 (Boughey & Vickerman)

The best/easiest way to approach this and the Rivock carvings as a whole is to reach the Silsden Road that curves round the southern edge of Rombalds Moor (whether it’s via East Morton, Riddlesden, Keighley or Silsden) and keep your eyes peeled for the singular large windmill. About 200 yards east of this is a small parking spot, big enough for a half-dozen vehicles. From here walk 450 yards east along the road till you hit the dirt-track/footpath up towards the moor. Follow the track up for about 400 yards and you’ll see the crags a half-mile ahead of you. Get up there to the Wondjina Stone and follow the walling east for about 175 yards where you’ll see a track-cum-clearing in the woods. Walk along and the first large stone on your left is what you’re after.

Archaeology & History

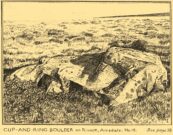

I first visited this carving in my teenage years in the 1970s, before the intrusive so-called “private” forest covered this landscape and when its petroglyphic compatriots were easier to find. Thankfully this one’s still pretty accessible and possesses a damn good clear design. It was rediscovered in the 1960s by Stuart Feather and his gang, zigzagging their way across the open moors, pulling back the heather to see what they might find. His description of it told how the stone,

“has two roughly level areas, one 18ins and the other 2 feet above ground level. Both (levels) have several well-preserved cup-and-ring markings on them. There are eight single cup-and-rings and 18 cups, two of the latter being joined by a clear channel seven inches long and 1½ inches wide. Nearly all the markings are unusually well preserved and the pocking marks are very clear.”

He also had “the impression that all the markings on this stone and possibly one other similar stone in the Rivock area have been carved by the same hand, as all the symbols are nearly identical in in type, size and execution.” (this other carving he’s referring to seems to be one about 170 yards to the north, where occasionally “offerings” have been found)

When John Hedges (1986) and his team checked the stone out he could only make out “seven cups with single rings, twenty two other cups”; whilst the ever descriptive Boughey & Vickerman (2003) saw “twenty-nine cups, eight with single rings.” Eight cup-and-rings is what most people see when the light’s right. There’s also a long, bent carved line on the lower level of the rock, running from near the middle of the stone out to the very edge. It seems to be man-made (although I may be wrong) – and I draw attention to it as this same feature exists on at least three of the other large and very ornamental cup-and-rings hereby within 300 yards of each other – and on these other carvings the long “line” is definitely artificial. Tis an intriguing characteristic…

When visiting this petroglyph you’ll notice how some of the carved elements on top of the stone are more eroded than those on the lower section. This is due to the fact that the lower section was only revealed by Feather and his team in the mid-20th century, after it had been covered in soil for countless centuries. As a result you can still see the peck-marks left by the implements that were used to make the carving, perhaps 5000 years ago!

The name of the stone was inspired by a local lady who saw an astronomical function in the design (I quite like it as well). Examples of petroglyphs representing myths of heavenly bodies have been described first-hand in some tribal cultures and, nowadays, even a number of archaeologists are making allusions about potential celestial features in some carvings in the British Isles. That doesn’t mean to say that it’s correct, but the idea’s far from unreasonable…

Anyhow – check this one out when you’re next up here. You’ll like it!

References:

- Bennett, Paul, “The Prehistoric Rock Art and Megalithic Remains of Rivock & District (parts 1 & 2),” in Earth, 3-4, 1986.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS 2003.

- Deacon, Vivien, The Rock Art Landscapes of Rombalds Moor, West Yorkshire, ArchaeoPress: Oxford 2020.

- Feather, Stuart, “Mid-Wharfedale Cup-and-Ring Markings – no.16 – Rivock,” in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, volume 8, no.10, 1963.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., “The Prehistoric Rock Art of Great Britain: A Survey of All Sites Bearing Motifs more Complex than Simple Cup-marks,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 55, 1989.

Acknowledgments: Huge thanks to Collette Walsh for use of her photos.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian