Standing Stone: OS Grid Reference – NO 15751 35578

Also Known as:

- Gallowshade

- Canmore ID 28479

Turn right off the A93 at Cargill onto the side road by Keepers Cottage and up the hill to Gladsfield Wood at the top on your right. Park up at the top side of the Wood and walk straight along the narrow track for around 450 yards and what may be the remains of the stone will be seen between a pair of mature trees.

Archaeology & History

In 1862 the stone was described in the Ordnance Survey Name Book for Perthshire:

‘And about 150 yards from the same object [Hangie’s Well], in a north-westerly direction, there is a small Standing Stone, having the appearance of the ancient monumental standing stones.’

It seems the stone had been removed by the time Fred Coles (1909) came to see it nearly fifty years later. He told us:

“On the day of my visit the mist was so abnormally dense and confusing that it was with considerable difficulty the wood itself was identified; and as its interior is an utter wilderness of trees, shrubs, brambles, broom, wild roses and tall grass, besides being a pheasantry, it is just possible that the monolith searched for evaded my zeal. I think not, however, because, hearing a hedger at work on the Newbigging side of the wood, I made for him; and after plying him with various questions, could get no statement to the effect that he had, though living so near, ever seen any conspicuously tall Stone in the wood.

“On retracing my steps, I searched a fresh portion of the wood, and noticed one biggish block of whinstone lying on the grass in a slight hollow of the ground. It was somewhat cubical, about 2 feet 6 inches square, and fractured. This may he a portion of the former monolith, possibly; and with this dubious result I had to be content.”

In 1967 the archaeologist O.G.S. Crawford described “a sharp-edged boulder standing near the spot marked on the map,” but was not certain if it was the stone. It had no markings on it.

Moving on to 2020, and I found the same impenetrable jungle that Coles described more than a century earlier. When a site has been destroyed I can normally take a photograph of where it once was, but not in this case. I continued westward over difficult and potentially ankle snapping terrain that had recently been replanted with conifer saplings, until I got out of the planting area to a line of mature trees next to the track through the wood.

One large elongated stone presented itself that had clearly lain there for many years judging from the moss growth, a short distance away at NO 15641 35478. Could this be the top part of the standing stone, dragged from its original position some 500 feet to the north-east? It is of grey whinstone, heavily veined at the base, with white quartz and tapering to a pointed tip. It has a squarish base measuring approximately 3 feet across by at least 2 feet deep and is some 7 feet in length. It doesn’t look to be natural, so is it a likely candidate for our missing stone? Felled by a man with a hammer and chisel and dragged by a heavy horse to the edge of the field as part of the ‘improvements’, so beloved of nineteenth century landowners…

We can’t prove it is the remains of Hangie’s Stone which may, after all, still lie buried in the boscage…

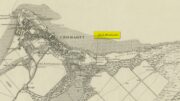

The stone in its original position was next to the Roman road from Camelon via Stirling and Muthill to Kirriemuir near to the junction of a road to Inchtuthill Roman Fort, so may have once been a way marker, although it is not of Roman origin.

References:

- Coles, Fred R., “Stone Circles Surveyed in Perthshire (South-east District),” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries Scotland, volume 43, 1909.

- Margary, Ivan D, Roman Roads in Britain, John Baker: London 1973.

- Ordnance Survey Name Book

- Sedgley, Jeffrey P., The Roman Milestones of Britain, BAR Reports No. 18: Oxford 1975.

© Paul T Hornby 2021