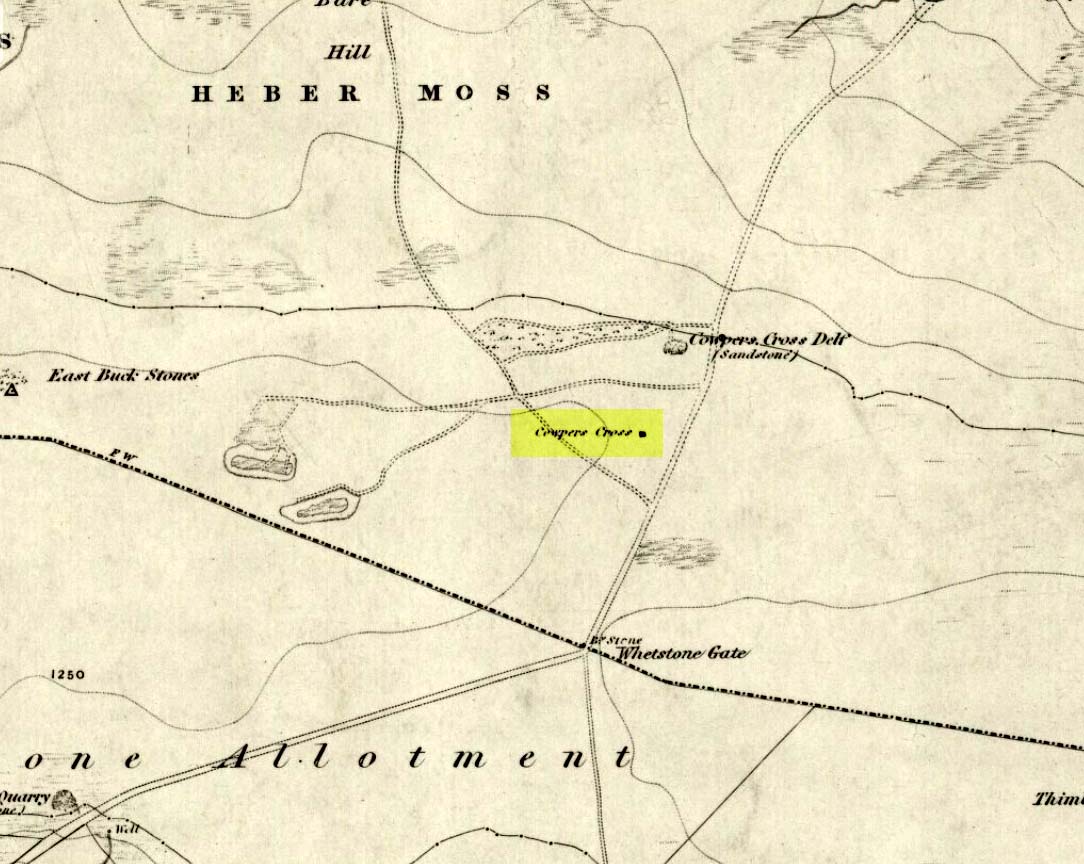

Wayside Cross (Destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 3519 5694

Also Known as:

Archaeology & History

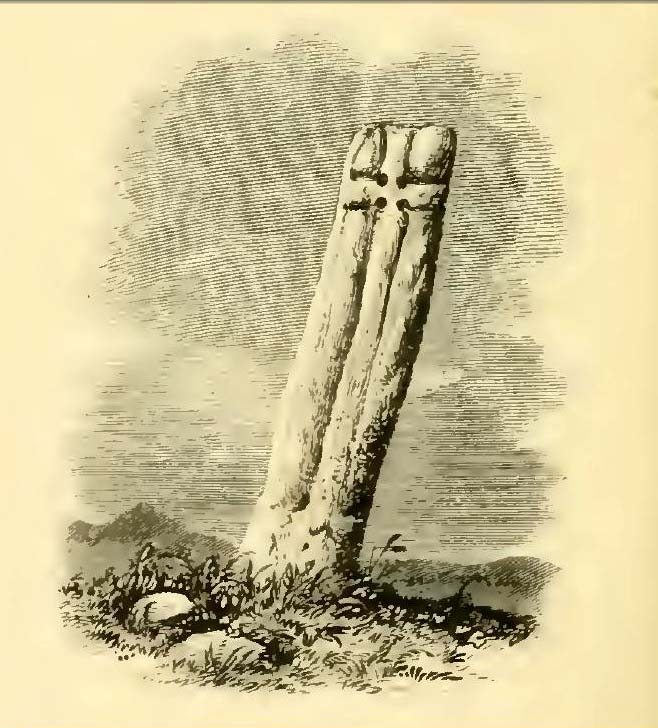

This long lost Cross could once be seen close to the Tudor era Byrnand Hall, which stood on the north side of the High Street. The Hall was demolished around 1780, and replaced by the present building, which is now a political club. The Cross was taken down around the same time, so we’re very fortunate to have a contemporary sketch.

Harry Speight (1906), the Great Yorkshire antiquarian, described the Cross when he was writing of the ‘big houses’ of Knaresborough, saying:

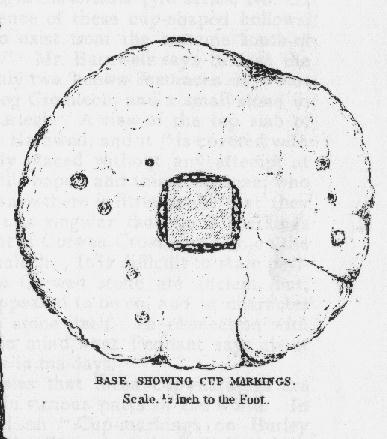

“Another notable old mansion was Byrnand Hall, which stood at the top of the High Street facing Gracious Street, and was rebuilt about a century ago. It was the property and seat for many generations of one of the leading families of Knaresborough, named Byrnand, one of its members being recorder of York in 1573. Opposite the house stood a very ancient stone cross, consisting of a plain upright column, without date or inscription, supported by several rudely-formed stones placed on three tiers or steps. It appears that one Richard Byrnand paid a fine and was permitted to enclose a cross standing on a piece of waste land then lately belonging to Robert Nessfield. The cross may be conjectured to have been either a memorial or boundary-stone. In those days ” it was not enough,” says the old antiquary, Hearne, ” to have the figure of the cross both on and in churches, chapels, and oratories, but it was put also in church-yards, and in every house, nay, many towns and villages were built in shape of it, and it was very common to fix it in the very streets and highways.

“This ancient relic, the site of which is now marked by a brass cross sunk in the causeway, was in after times called the Byrnand Hall Cross, from its proximity to the house of the same name. It stands on the road equidistant between York and Leeds, being eighteen miles from either place.”

At the end of the eighteenth century, E. Hargrove wrote:

“The (Byrnand) family mansion was situated at the end of the High-street, leading towards York. Near it formerly stood an ancient Cross, which being placed on the outside of the Rampart, and opposite to the entrance into the borough, seems to have been similar in situation, and probably may have been used for the same purpose, as that mentioned by Mr. Pennant, in his History of London, which stood without the city, opposite to Chester Inn; and here, according to the simplicity of the age, in the year 1294, and at other times, the magistrates sat to administer justice. Byrnand-Hall hath been lately rebuilt, by Mr. William Manby, who took down the remains of the old Cross, and left a cruciform stone in the pavement, which will mark the place to future times.”

Abbot J.I. Cummins, writing in the 1920s about the Catholic history of Knaresborough, told:

“Of the Byrnand Cross beyond the old town ditch the site is now marked in York Place by a brass cross let into the pavement for Christians to trample on.”

The Cross occupied an important position in the Knaresborough of old, at one of the highest points of the town by the junction of the modern High Street and Gracious Street, this latter being the road down the hill to the riverside and the troglodytic shrines of St Robert of Knaresborough and Our Lady.

Assuming the eighteenth century drawing is an accurate representation of the Cross, it does give the impression of considerable antiquity, and looks to have been 15-16 feet (4.75m.) high. From its appearance it looks like either a prehistoric monolith or an Anglo-Saxon ‘stapol‘ or column, and if it was the latter, it may have been erected to replace an earlier heathen wooden column or sacred tree following the replacement of the old beliefs by Christianity. If so, there may be no reason to deny Hargrove’s speculation that Byrnand Hall Cross once had a similar juridical function to the Chester Inn Cross in London.

References:

- Bintley, Michael D.J., Trees in the Religions of Early Medieval England, Woodbridge, Suffolk, Boydell Press 2015.

- Cummins, J.I., “Knaresborough,” in The Ampleforth Journal, Vol XXIV, No II, Spring 1929.

- Hargrove, E., The History of the Castle, Town and Forest of Knaresborough, 5th Edition, Knaresborough 1790.

- Speight, H., Nidderdale, from Nun Monkton to Whernside, London, Elliot Stock, 1906.

© Paul T. Hornby, 2020

(Note – Knaresborough was at the time in the historic County of the West Riding of Yorkshire)