Sacred Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 3953 1570

Archaeology & History

The precise whereabouts of this site isn’t known with absolute certainty, but, following research by the respected folklorist and pagan historian Steve Jones of Wakefield, the grid-reference cited here has a high degree of probability about it. I certainly agree with Steve about its location.

Known about in the 19th century, I was fortunate in coming across what seems to be the only reference to the place whilst perusing the scrapbook notes of local historian John Wilson (1903). Were it not for him we would have lost all knowledge of its existence and the local tale told of it, albeit watered into a dying belief in these supernatural creatures, would have faded completely before its final physical demise. Wilson was described as a “diligent a student of local history,” who possessed a great collection of rare booklets and pamphlets on Yorkshire history and was a “careful an observer and recorder of all pertaining to past times.” Of this Fairy Well, Wilson scribed the following poem:

At Nostell is a Fairy Well,

Hard by the margin of a wood

Wherein once dwelt, as old men tell,

The little folks of fickle mood ;

Till smoke and steam denied the dell

And made them quit both wood and well.Blythe Henry Carr, mine ancient friend,

— So bravely keeping on his feet ;

May death long spare him,

still to wend His way along the village street,

Within the cobbler’s shop to spend

A pleasant hour — mine ancient friend.The woodman at the Priory

In old Sir Rowland’s halcyon days

Was Thomas Watson, gay and free,

Who roused with song the woodland ways

A friend of Henry Carr’s was he,

—The woodman at the Priory.This Watson many a tale could tell

Of fairies red and fairies green,

That in the wood and by the well

On summer evenings he had seen:

Of elves that thereabouts did dwell

This Watson many a tale could tell.Whoever heard of such a thing!

He said that persons, known to him,

At eve would flasks of liquor bring,

And leave them, lying near the brim

Of this — the wondrous Fairy Spring —

Whoever heard of such a thing !Was ever such a tale yet told ?

He said, that, when the morning came,

Each flask lay empty, and, behold !

Near each a drunken elf. O, shame !

The vice of those of mortal mould :

— Was ever such a tale yet told ?Then question I mine ancient friend:

“Did no one seize the tipsy sprites? ”

“Not they ! for sudden is his end

On whom the fairy vengeance lights.”

With solemn eyes that fear portend

Thus answers me mine ancient friend.

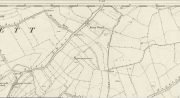

Steve Jones already knew of the Fairy Wood, which was highlighted on the 1841 and 1854 6-inch-to-the-mile OS-map of the area—but no “Well” is shown in the woods. However, as Steve discovered, following a subsequent visit by the Ordnance Survey lads in 1891, they showed on their 25-inch-to-the-mile map of the woods a distinct small pond in the trees not far from the roadside. This, he thought, was probably the Fairy Well referred to by Wilson. It would seem so. Adjacent to the woods, the 1853 Tithe Award cite the existence of a field also dedicated to the fairy folk, known simply as Fairy Close.

References:

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 1, Cambridge University Press 1961

- Wilson, John, Verses and Notes, A. Hill: Corley 1903.

Acknowledgements:

Huge thanks to the research by Steve Jones of Wakefield, without whose work the location of the Fairy Well would have remained a mystery. Also, thanks as always for use of the early edition OS-maps, Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian