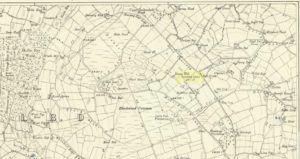

Sacred Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 17567 35473

Also Known as:

- Pendragon Well

Archaeology & History

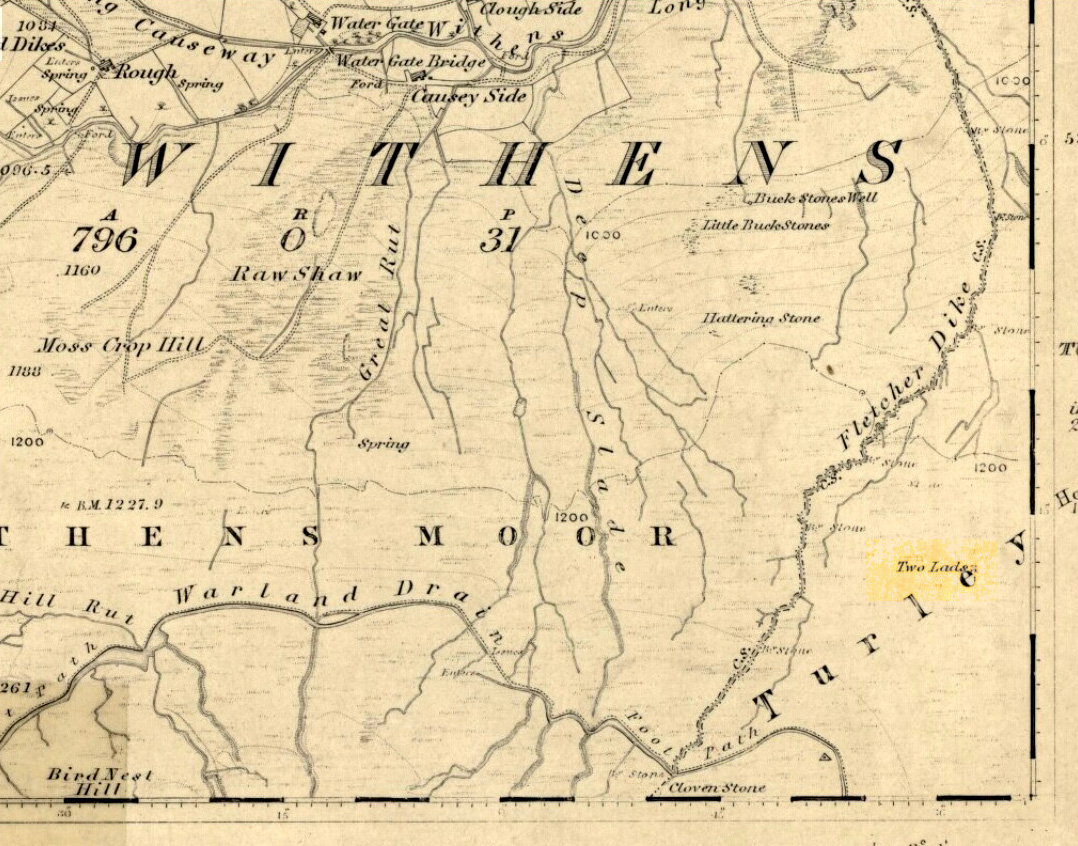

A most curious place: this ‘Well of the Dragon’ as it was first called (on the 1852 OS-map) and subsequently the ‘Pendragon Well’ (on the 1922 map) just off Pendragon Lane, seems to have been forgotten in both folklore and history. I grew up round here and no legends of dragons were known, either in my life, nor that of the old folks I knew; nor any pub of that name that might account for it.

Equally unexplained is the name of the adjacent ‘Pendragon Lane’, which has been known as that for some 175 years. We have no Arthurian myths anywhere in West Yorkshire that remains in folk memory—and certainly nothing hereby that accounts for it.

As for possible landscape associations (i.e., serpentine geological features), nothing in the vicinity has any bearing on the name. Indeed, the only thing of any potential relevance was the former existence of a healing rock known as the Wart Stone, some 100 yards to the east at Bolton Junction. Such stones are usually possessed of naturally-worn ‘bowls’ of some sort on top of the rock—akin to large cup-markings—into which water collected that was used to rid the sufferer of warts or similar skin afflictions. But such an association seems very unlikely.

The only thing we can say of this Dragon Well is that probably, in times gone by, a folktale or legend existed of a dragon in the neighbourhood that had some association with the waters here. Dragons are invariably related to early animistic creation myths, and this site may have been all that remained of such a forgotten tale. The nearest other place in West Yorkshire with dragon associations is six miles northwest of here on the south-side of Ilkley Moor. In Britain there are a number of other Dragon Wells, the closest of which is in South Yorkshire.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian