Sacred Well: OS Grid Reference — SE 0967 3251?

Archaeology & History

Is this the site of the lost Jim Cravens Well on the 1852 map?

Another well with considerable supernatural renown was this little-known site near the old village of Thornton, on the western outskirts of Bradford. We’re not 100% sure about its exact location, but the grid-reference cited here is of an old ‘Well’ that was highlighted on the first Ordnance Survey map of the region, at the end of solitary path which led to it and nowhere else. Our only documentary information comes from Elizabeth’s Southwart’s (1932) fine old book on the folk life of the old village, as it once was. At a place once known as Bent Ing Bottom, just south of the old village, is where it used to be known. The name of this Well is also curious, as no historian has yet worked out who the ‘Jim Craven’ was, nor what his relationship to the site might have been. It’s the folklore of it, however, which brings it the attention it deserves.

Folklore

In Elizabeth Southwart’s (1923) work, she told us that the place once known as “Bent Ing Bottoms have lost their romance.” She continued:

“Whether the golfers have driven it away—for the fields now form part of the Thornton Golf Links—or whether the advance of modernity in other forms is to blame, it is difficult to say. Once they were the haunts of “Peggy-Wi-T’-Lantern” and the Bloody-tongue. Peggy, a dame in a white mob cap, kilted skirt and white stockings, walked about with a lantern, enticing the unwary traveller to his doom. She was given to wandering, for, they say, Jim Craven Well, half a mile away, was a place to be avoided after nightfall.

“The Bloody-tongue was a great dog, with staring red eyes, a tail as big as the branch of a tree, and a lolling tongue that dripped blood. When he drank from the beck (known as the Pinch Beck, PB) the water ran red right past the bridge, and away down—down—nearly to Bradford town. As soon as it was quite dark he would lope up the narrow flagged causeway to the cottage at the top of Bent Ing on the north side, give one deep bark, then the woman who lived there would come out and feed him. What he ate we never knew, but I can bear testimony to the delicious taste of the toffee she made.

“When the dark was coming we used to sit on the filled-in pit, which makes a hump in the middle of the field, and wait for him. The sun would sink redly, through the arches of the viaduct, the trees that lined the beck would grow an ever darker green until they became black, the beck would begin to gurgle and gulp in a queer way; and down in the hollow we would hear a whimper, a whine, a moan, a snarl. Then, with scalps and spines playing queer tricks, we would wait and wait. But none of our little band ever saw him, except one girl, and she saw him every time.

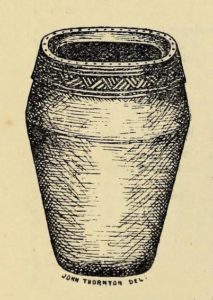

“One Saturday a girl who lived at Headley came to a birthday party in the village, and was persuaded to stay to the end by her friends, who promised to see her ‘a-gaiterds’ if she would. As soon as the party was over the brave little group started out. But when they reached the end of the passage which leads to the fields, and gazed into the black well, at the bottom of which lurked the Bloody-tongue, one of them suggested that Mary should go alone, and they would wait there to see if anything happened to her.

“Mary was reluctant, but had no choice in the matter, for go home she must. They waited, according to promise, listening to her footsteps on the path, and occasionally shouting into the darkness:

““Are you all right, Mary?”

““Ay!” would come the response.

“And well was it for Mary that the Gytrash had business elsewhere that night, for her friends confess now that at the first sound of a scream they would have fled back to lights and home.

“We wonder sometimes if the Booody-tongue were not better than his reputation, for he lived there many years and there was never a single case known of man, woman or child who got a bite from his teeth, or a scratch from his claws. Now he is gone, nobody knows whither, though there have been rumours that he has been seen wandering disconsolately along Egypt Road, whimpering quietly to himself, creeping into the shadows when a human being approached, and, when a lantern was flashed on him, giving one sad, reproachful glance from his red eyes before he vanished from sight.”

Southwart later tells us that the ghostly dog travelled into the north and vanished. From the description she gives of the children walking their friend to “the end of the passage which leads to the fields, and gazed into the black well, at the bottom of which lurked the Bloody-tongue,” I can only surmise that the solitary well shown on the very first OS-map of Thornton at the coordinate given above is the place in question.

The ‘Bloody Tongue’ is first mentioned in Yorkshire folklore, I think, by Roger Storrs, in his article on holy wells in 1888, where he tells it to be one of the mysterious beings that live, usually at the bottom of the waters and almost universally used “to deter children from playing in dangerous proximity to a well.”

From the description of the waters turning red when the ghostly dog drank from it, we have a mythic account of when the waters occasionally turned red from the iron-bearing waters (chalybeate) which, obviously, wasn’t like this at all times. Whether this was a sporadic, unpredictable flow of iron in the waters, or a cyclical pattern of the water-flows, we are not told (which would imply, moreso, that it was sporadic). The folklore about this ghost and its appearance with another elemental creature along an old straight track running north from Upper Headley Hall to Thornton is intriguing—as in many old pre-christian traditions, North is the airt, or direction, representing Death; and black dogs are traditionally guardians of underworld treasures in the land of the Dead. With the plethora of other animistic folktales once known in this district (boggarts or goblins were known in nearby woods, wells and farms) it is likely that the origin of such folklore dates way back into antiquity.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of West Yorkshire, forthcoming

- Southwart, Elizabeth, Bronte Moors and Villages: From Thornton to Haworth, John Lane Bodley Head: London 1923.

- Storrs, Roger, ‘Legends and Traditions of Wells,’ in Yorkshire Folk-lore Journal – volume 1 (ed. J. Horsfall Turner) 1888.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian