Cross (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 14390 40601

Also Known as:

- Rerehowe Cross

Archaeology & History

Once found on the other side of the road from the prehistoric circle of Acrehowe Hill, this old cross was destroyed sometime in the first half of the 19th century by one of the stewards to the Lady of the Manor of Baildon, a Mr Walker. It’s unlikely that Mr Walker would have performed this act without direct orders from the Lady of the Manor, so the destruction should really be laid at the feet of the land-owner, who’ve got a habit of destroying archaeological sites up and down the land, even today.

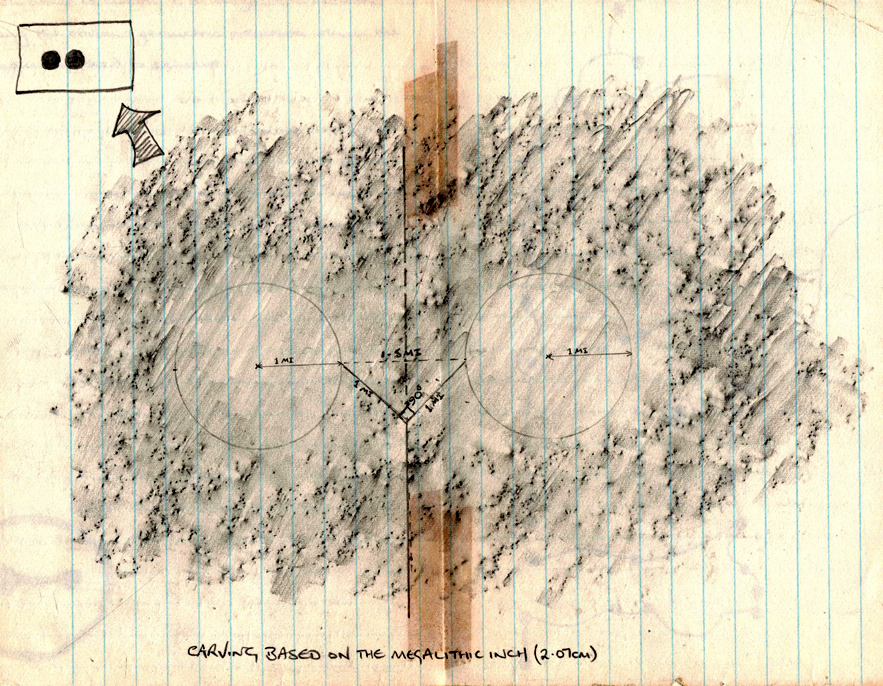

Found near the crown of a small hill on the horizon whether you’re coming from Eldwick- or Baildon-side, the cross was erected (probably between the 12th and 14th centuries) amidst a cluster of heathen burials and cup-and-rings, many of which would have been known by local peasants as having old lore or superstitions about them. So the church commandeered this spot, desacralized it and no doubt enacted profane rites around it under the auspice of some spurious christian law. They did that sorta thing with every non-christian site they ever came across—or simply vandalised it, much as many of them still do today. Sadly we know not the exact history of the old cross: whether it was an old standing stone on the crown of this hill which they defaced and made into a cross, or whether they erected their own monument, we’ll never know. But the idea of a once-proud monolith standing here is a strong possibility, considering its position in the landscape and the stone rings of Pennythorn and Acrehowe close by (cup-and-ring stones such as carving no.184 are also close by).

The cross itself once gained an additional incorrect title by the cartographers of the period, who named it Rerehowe Cross—but this was simply a spelling mistake and its newly-found title didn’t last long. The local industrial historian William Cudworth (1876) described the lost cross in his large work, where he told that,

“many of the inhabitants can remember and point out the exact spot where it stood, and no doubt could find some of the stones of which it was composed. It was destroyed by one of the overseers and a large portion of it used for fence stones.”

Harry Speight (a.k.a. ‘Johnnie Gray’) and others also mentioned the passing of this old stone, but give no additional information.

Folklore

In William Cudworth’s description of this site he told how “the village tradition is that it was put up in commemoration of a great battle that was fought on the Moor” at Baildon; but W.P. Baildon (1913) thought this was unlikely. Instead, he cited an 1848 Name Book reference dug out by W.E. Preston, which told that on the summit of Acrehowe Hill,

“Here stood a cross which, according to traditional evidence was erected at the period that markets were held at Baildon, in consequence of a plague which prevented the country people from visiting the village with provisions, etc. The site of its base is very apparent, being circular, about 8 feet in diameter. A large flag stone with the stump of the cross remaining in its centre, was pulled up and destroyed by Mr Walker (Baildon Hall) a few years since.”

References:

- Baildon, W. Paley, Baildon and the Baildons (parts 1-15), St. Catherines: Adelphi 1913-26.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Colls, J.M.N., ‘Letter upon some Early Remains Discovered in Yorkshire,’ in Archaeologia, volume 31, 1846.

- Cudworth, William, Round about Bradford, Thomas Brear: Bradford 1876.

- Gray, Johnnie, Through Airedale from Goole to Malham, Walker & Laycock: Leeds 1891.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian