Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SD 80519 66474

Also Known as:

- Borrins Top

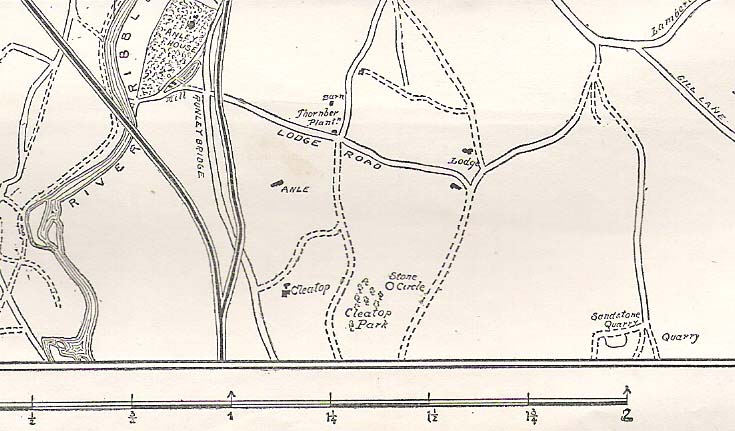

From Settle, take the same direction as if you’re visiting the giant Apronful of Stones cairn. Walk past it, keeping to the walling for 350 yards (319m) until you reach the gate on your right. Go through this and walk along the grassy footpath ahead of you for 75 yards (68.5m) and there, right by your left-hand side, you’ll see this low grassy circular embanked monument, or cairn circle.

Archaeology & History

This gorgeous, little-known cairn circle, hiding almost unseen beside the ancient grassy pathway that leads down to the haunted Borrins Wood, sits innocently, forgotten by those who would claim its importance. When this overgrown ring of stones was first built, the trees of Borrins Wood grew around the sacred court of this monument, watching rites committed to the ancestors, annually no doubt at the very least, under guidance of the Moon. But now such ways have been swept from the memory of those living, into worlds made-up of artifacts, linear time and dualist ideals, and our thoughts when brought here are encloaked by beliefs not worthy of such a place. Like many other small rings of stone, this was important for the rites of the dead. For here we can see a small stone-lined cist (grave) near the middle still growing from the Earth, with the small outer ring encircling the place of rites. It was obviously of ‘religious’ importance to those who lived here, probably even centuries after initial construction.

Similar in size and structure to the Roms Law Circle on Burley Moor, this site on the hills above Giggleswick seems to be Bronze Age in nature. From outer-edge to outer-edge the rough circular monument measures approximately 14½ yards (13m) north-south, by 15½ yards (14m) east-west, with an outer circumference of about 49 yards (43m). The edges of the ring, as you can see in the photos, is made up of an embankment of thousands of small stones and rubble, measuring between 1-2 feet high and between 2-3 yards across. The old cist in the middle of the ring—about 1 yard by 2 yards—has been dug into at some time in the past and a small mound of stones surround this central grave. The entire monument is very much overgrown, but still appears to be in relatively good condition. A new excavation of this and nearby prehistoric monuments would prove worthwhile.

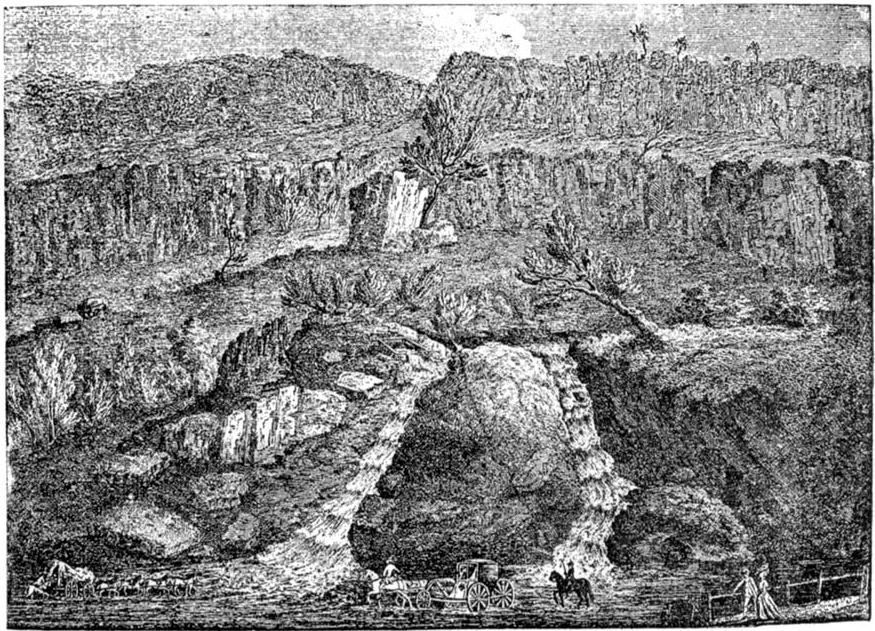

The ruined circle has a tranquil spirit, enclosed within a rich green panoramic landscape, enhanced with the breaking of old limestone and gnarled hawthorns. Other prehistoric cairns can be found nearby and the remains of a previously unrecorded prehistoric enclosure stands out on a small rise 164 yards (150m) southeast. We’ve found other unrecorded prehistoric remains in this arena which will be added to TNA, as and when…

References:

- Speight, Harry, The Craven and Northwest Yorkshire Highlands, Elliott Stock: London 1892.

Links:

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian