Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SD 94945 65270

Also Known as:

-

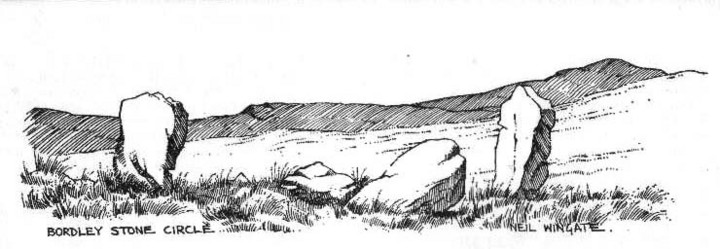

Bordley Circle

Getting Here

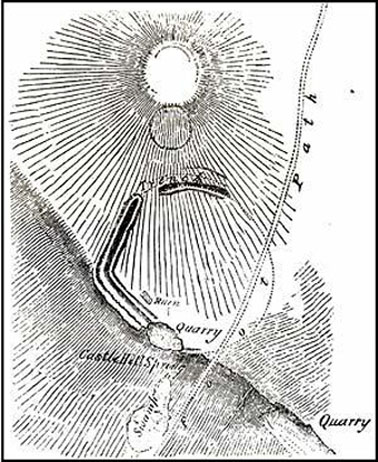

From Threshfield, go up Skirethorns Lane for about 1/2 mile, where the lane takes a sharp right. Continue uphill for nearly 2 miles to a metal gate. Go through the gate, where you’ll see a pair of curious standing stones ahead of you, but instead walk about 250 yards along the line of the old field wall running to the west. You’ll see on the modern OS-map that a ‘cairn’ is shown: this is where you’re heading!

Archaeology & History

First highlighted on the 1852 OS-map of Bordley and district, this is a lovely site in a beautiful setting, surrounded by a veritable mass of other prehistoric remains at all quarters, including the large settlement of Hammond Close immediately south, the little-known settlement at Kealcup to the west, the Lantern Holes settlement up the hill immediately north, some standing stones due east, and much more. Although it was described in Aubrey Burl’s Four Posters (1988) as just such a type of megalithic relic (a “four-poster stone circle”), an earlier description of the site from the mighty pen of Harry Speight (1892) told of a much more complete ring of stones, with trilithon to boot. He wrote:

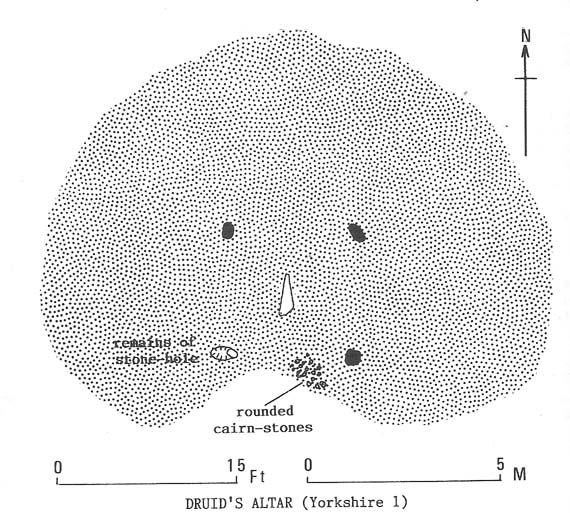

“This prehistoric relic consists of a round stone and earthen mound, about 150 feet in circumference and 3 feet high, and was formerly surrounded by a circle of upright stones, only three of which are now left standing. On one side was a large flat stone resting upon two others, and known as the Druid’s Altar. On the adjoining land an ancient iron spear-head was found some years ago, and fragments of rudely-fashioned pottery have also from time to time turned up in the same neighbourhood.”

Edmund Bogg’s (1904) description following his own visit a few years later described this “remains of Druidical sacrifice” as consisting of,

“a mound some four feet high, and fifty yards round the outer rim. In the centre are two upright stones about four feet in length; and others nearly buried in the mound. Numerous stones from this circle have been used in building the adjoining walls.”

A decade later another writer (Lewis 1914) merely copied what Speight and Bogg had recited previously. And whatever the modern books might tell of its status, I think we can safely assert that this was originally a much more substantial monument than the humble four-poster stone circle that meets our eye nowadays. Our megalithic magus, Aubrey Burl (1988), wrote the following on Bordley’s druidical stones:

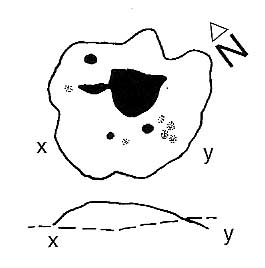

“On a circular mound 41ft (12.5m) across and 3ft (1m) high, three stones of local limestone form the corners of a rectangle 11ft 6in (3.5m) square, from which the SW stone is missing. At its corner is ‘a stump, possibly the base of a prostrate stone,’ 5ft 10in (1.8m) long, now lying near the centre. The tallest stone, 3ft 7in (1.1m) high is at the south-east. The sides of the square are close to the cardinal points. Between the SW and SE stones is a scatter of round cairnstones… Characteristically, the 4-Poster stands at the edge of a terrace from which the lands falls steeply to the west.”

The Druid’s Altar seems to have originally been a large prehistoric tomb, perhaps even a chambered cairn. Its situation in the landscape where it holds a circle of many outlying hills to attention, almost in the centre of them all, was evidently of some importance. The only geographical ‘opening’ from here is to the south, where a long open valley widens to capture the grandeur of Pendle Hill, many miles away. This would not have been insignificant.

We must also draw attention to what may be a secondary tumulus of similar size and form to the mound that the Druid’s Altar sits upon only some 25 yards to the west of the “circle”. The shape and form of this second mound is similar to that of our Druid’s Circle — though to date, it seems that no archaeologist has paid attention to this secondary feature. It measures some 21 yards (east-west) x 19 yards (north-south) in diameter and has the appearance of a tumulus or buried cairn. The mound may be of a purely geological nature, but this cannot safely be asserted until the attention of the spade has been brought here.

Folklore

Although we have nothing directly associated with the circle, the surrounding hills here have long been known as the abode of faerie-folk. Threshfield — in whose parish this circle lies — is renowned for it. There have been accounts of curious light phenomena here too. Modern alignment lore tells the site to be related to the peaked tomb above Seaty Hill, equinox west of here.

References:

- Bogg, Edmund, Higher Wharfeland, James Miles: Otley 1904.

- Burl, Aubrey, Four Posters: Bronze Age Stone Circles of Western Europe, BAR 195: Oxford 1988.

- Feather, S.W. & Manby, T.G., ‘Prehistoric Chambered Tombs of the Pennines,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 42, 1970.

- Lewis, A.L., ‘Standing Stones and Stone Circles in Yorkshire,’ in Man, no.83, 1914.

- Raistrick, Arthur, ‘The Bronze Age in West Yorkshire,’ in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 29, 1929.

- Speight, Harry, The Craven and Northwest Yorkshire Highlands, Elliott Stock: London 1892.

- Wingate, Neil, Grassington and Wharfedale, Grassington 1977.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian