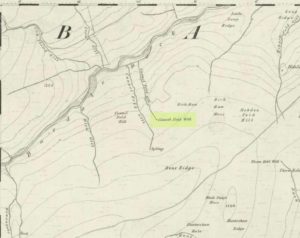

Enclosure: OS Grid Reference – SD 95415 69019

Going along the B6160 road from Grassington to Kettlewell and taking the little road to Arncliffe on your left just a few hundred yards past Kilnsey Crags, after ¾ of a mile keep your eyes peeled for the small parking spot on the left-side of the road, with the steep rocky stream that leads up to the Sleet Gill Cave. Walk up this steep slope, following the same directions to reach the Sleets Gill Top enclosure. From here you’ll notice a large gap in the rocky crags about 200 yards WSW that you can walk through. On the other side of this gap, along a small footpath about another 200 yards along you’ll reach a large ovoid rock. Just before this, on your right, is a long rocky rise with distinct drystone walling below it. That’s the spot!

Archaeology & History

Encircling a slightly sloping area of ground that stretches out beneath a long line of limestone crags is this notable walled enclosure running almost the full length of the rocky ridge. Measuring 40 yards (36m) in length by 10 yards (9m) across at its greatest width, this elongated rectangular enclosure has all attributes of being Iron Age in origin, much like many others in this area. However, in comparison with the others close by, this is a pretty small construction and—if used for human habitation, as is likely—would have housed only two or three families.

Within the enclosure itself, near its western end, we find an internal line of walling that creates a single room: enough for a single family, or perhaps even where animals were kept. Only an excavation would tell us for sure.

One notable interesting feature exists roughly halfway along the enclosure, up against the crag itself: here is small man-made stone “cupboard” of sorts, akin to some modern pantry. You’ll get an idea of it in the photo. At first I wondered if this would have been a sleeping space, but, unless it was where a shaman liked to encase him/herself inside a domestic household cave (highly improbable), it would have served a simple pragmatic function. Make up your own mind.

I liked this place. It’s surrounded by crags on almost all sides with some ancient spirit-infested rocky hills very close by, giving it a beautiful ambience. Immediately below the enclosure is what looks to be a large dried-up pool, which was probably well stocked with fish. A perfect living environment. Check it out!

References:

- Raistrick, Arthur, Prehistoric Yorkshire, Dalesman: Clapham 1964.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian