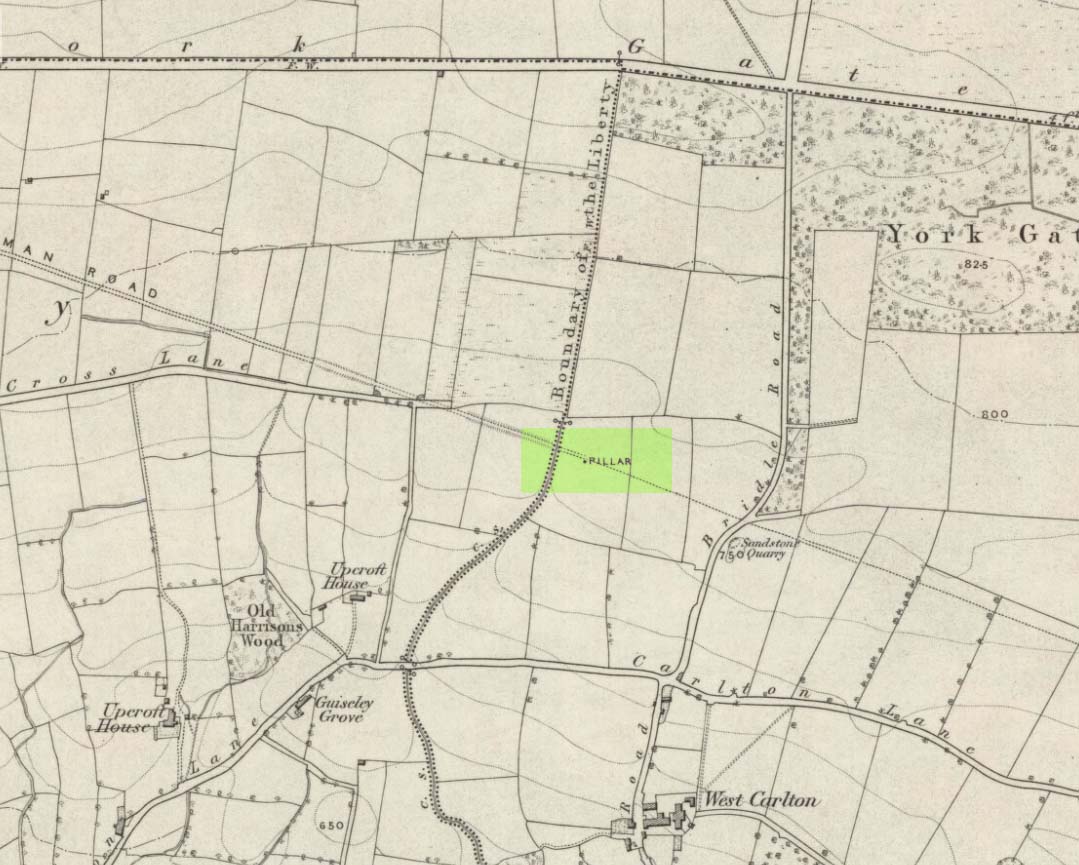

Earthworks: OS Grid Reference – SE 067 354

Getting Here

C.F. Forshaw (1908) told us that “this Castlestead…lies on the high ground between Cullingworth and Denholme, about 300 yards east of the point where te Cullingworth Road meets the Halifax-Keighley Road in Manywells Height, and over looks Buck Park Woods and the beck flowing down a deep ravine to enter the head of Hewenden Reservoir. A little to the north lies Moat Hill Farm…and the ancient burial place therewith associated.” Very little remains of the site can be seen.

Archaeology & History

Just over a mile southeast of the site of (virtually) the same name — the Castlestead Ring — this here Castle Stead site had me thinking that both sites were one and the same (poor research on my behalf I’m afraid). At the moment, the archaeological period of when this site was constructed remains unknown. Thought by Forshaw (1908) to be “almost certainly a hitherto unknown Roman entrenchment,” the very slight remains left here could be Iron Age or Romano-British. In his lengthy article on the remains that could be seen here more than 100 years ago, Mr Forshaw told us:

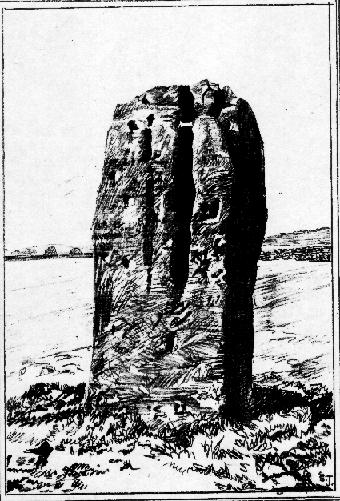

“Several fields hereabouts bear the name Castlestead and one of these contains the entrenchment, which almost coincides within its area… The reason for the selection of this site is clear, for on no side is it commanded by higher ground: whilst one face has a natural fortification of a rock scar impassable at most points and easily accessible at none. Here very little art would make the position impregnable in primitive warfare, and it is noticeable that the most suitable part of the verge has been selected, and almost the whole of the scar has been included. It is, however, only right to state that stone has been quarried here within living memory and this may have altered the ground considerably, and may account for several features mentioned hereafter.

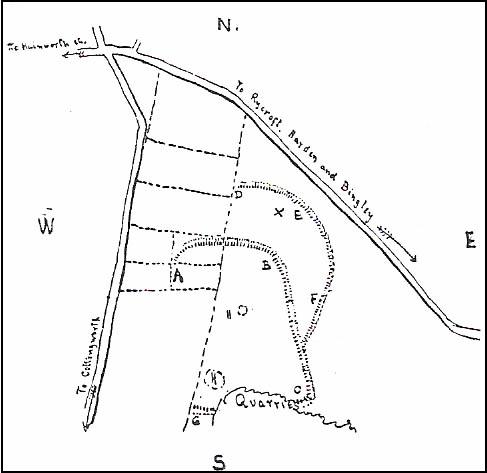

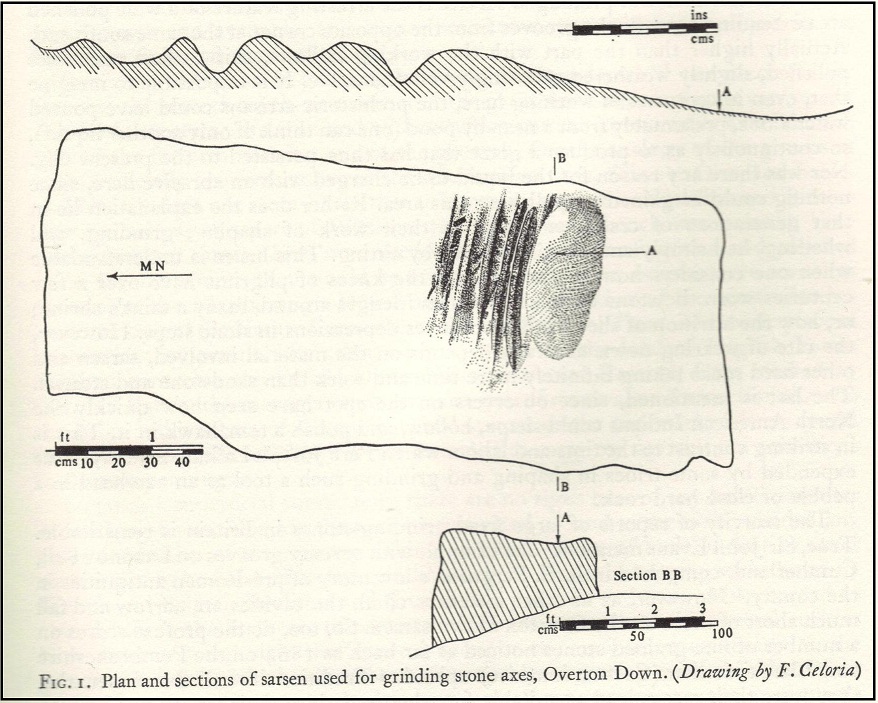

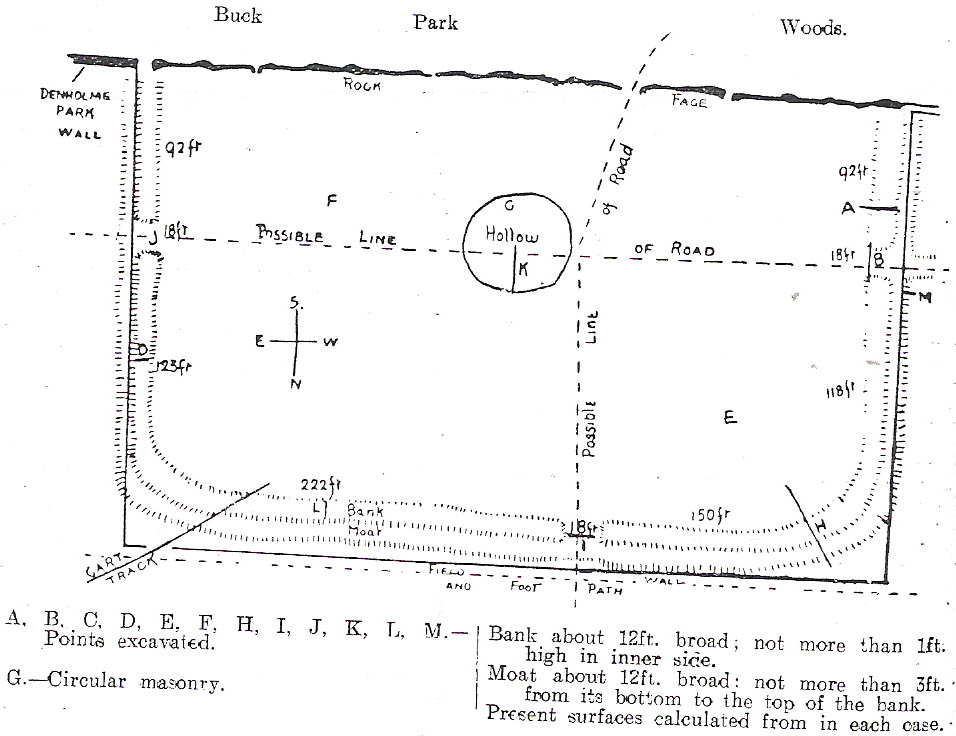

“The accompanying plan (above) will make the outline of the fortification clear, and from it one can readily recognise the usual Roman form. The moat and bank, the quadrangular shape with rounded corners and the entrances on three sides (and possibly on the fourth also) are characteristic. The unusual point is the selection of a natural fortification for one (the south) side.

“The question at once arises: was this a permanent stone fort? Clearly not, for the bank has been cut across at four places (A, D, H & L) and not only was no stone found — beyond such odds and ends as may be seen in any field — but the deeper, undisturbed layers of silt showed no signs of a trench in which foundations might have stood. It is noticeable that there are more stones on the crown of the bank than elsewhere. This I take to be the remains of what was thrown up in the bank. The field has been cultivated many years, so that the bank has been much reduced in height and the moat filled up.

“The original height of the bank is difficult to guess, but the moat was about three feet deeper than at present at the point H, and from the amount of soil removed we may imagine the bank about five feet higher than it is now, and solid at that; this makes a total outside slope of about 10 feet, a very formidable obstacle to surmount in the face of opposition, especially is strengthened by a stockade, such as was possibly present.The remains of the bank are capped with a layer of some six inches of bluish, silty clay. This was evidently placed there deliberately, and is in accordance with Roman work as seen elsewhere (e.g., at Castleshaw, near Oldham). There is also some slight evidence that, as at Castleshaw, the moat was once faced with irregular pieces of flat stone. The moat was some 18 feet across at the top, six feet at the bottom and five feet deep. The east and west sides were probably less strongly entrenched. Certainly the moat was much less, for rock lies only just below the sod, halfway along the western side. When the southern face is examined there are more signs of stonework, however, for where the rock is deficient the gap is filled with the remains of a dry wall which has some peculiar characteristics. In places the lower part of this wall is formed of roughly-shaped oblong blocks of large size (one has a face of 57 x 17 inches), arranged in definite tiers. This is not like an ordinary field fence, and differs even more from the ancient wall marked (probably erroneously) as Denholme Park Wall on the Ordnance map, which it continues: so it is conceivable that it may be Roman work. There is now little or no sign of a bank along the rocks bounding the southern side of the camp, but it is probable that something once existed to give cover to the defenders, and we may well imagine a low dry wall continuous with the fragments just described: and it is rather noticeable that there are more squared stones in the walls of this field than in others in the neighbourhood.

“There are no traces of buildings within the lines so far as the present investigations go, nor signs of prolonged occupation at the site. I have dug at the points indicated (on the map above) and came upon rock or disturbed silt in each case. The circular shallow hollow in the centre seems natural. It is to be remarked that the average depth of surface soil in this field is unusual, more than one foot in fact.”

Mr Forshaw then goes on to ask a series of questions, followed by his own particular answers and theory relating to the nature of these earthworks. Hopefully you won’t mind if I cite his ideas in full, despite him thinking that the remains here are of Roman origin (remains of which I don’t really wanna include on TNA). He continued:

“Was this camp on the course of a Roman road? One can only say that no definite road exists at the entrances now, but there seems some ground for thinking that a surface was prepared…at the western entrance for two reasons:

1. Just to the north the rock is covered with made soil only; but in the entrance itself irregular stones are packed in a level, solid manner, giving a strong impression of artificiality. At the southern verge of the entrance this layer ends abruptly in a line at right angles to the bank, and here it is based not on rock, but on natural silt.

2. A slight hollow runs straight westward from it for some twenty yards through the next field. This may represent a destroyed road.”

Mr Forshaw then makes a few attempts to justify this idea, including notices of footpaths and linear features near the site, aswell as citing earlier historical sources that describe Roman roads — but the ones cited are some considerable distance from this site. In summing up, he notes how no Roman finds were made here — nor indeed any finds from earlier periods — but he opted for the site being a temporary Roman outpost. The more recent opinions of this place are that it was of late Iron Age or Romano-British origin.

References:

- Cudworth, William, Round about Bradford, Thomas Brear: Bradford 1876.

- Forshaw, C.F., ‘Castlestead, near Cullingworth,’ in Yorkshire Notes and Queries – volume 4, H.C. Derwent: Bradford 1908.

- Hindley, Reg, Oxenhope: The Making of a Pennine Community, Amadeus: Cleckheaton 2004.

- James, John, The History and Topography of Bradford, Longmans: London 1876.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period,’ in Faull & Moorhouse’s, West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey to AD 1500 – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Varley, Raymond, “The Excavation of Castle Stead at Manywells Height, near Cullingworth, West Yorkshire,” in Transactions of the Hunter Archaeological Society, volume 19, 1997.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian