Cup-Marked Stone (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NX 0010 5411

Archaeology & History

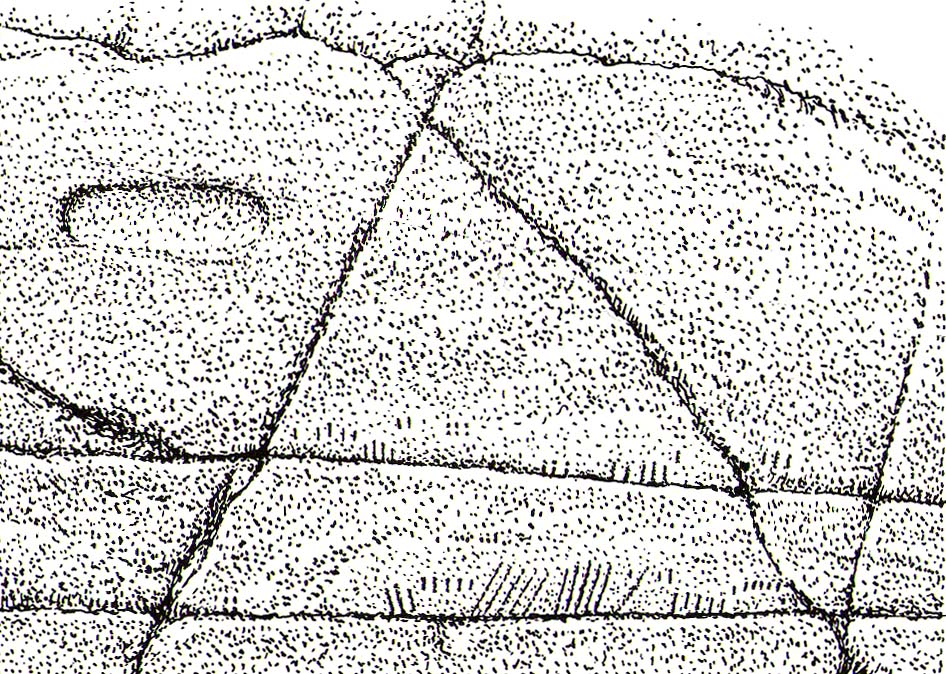

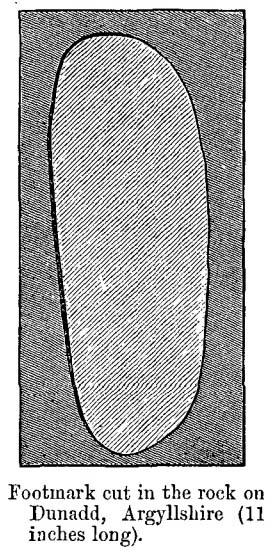

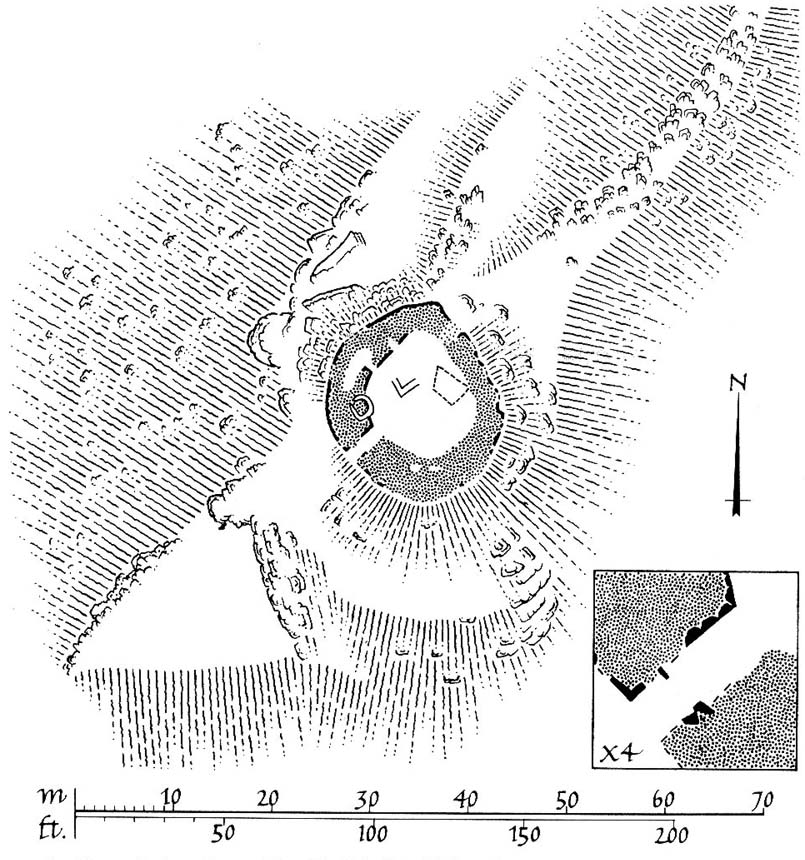

Very little is known about this long-lost carving, whose primary information comes from the folklore records. Apparently it was found on a rock a short distance south of the destroyed St. Patrick’s Well and the two sites seem to have had a traditional relationship with each other. The carving had a foot-shaped motif on the rock, and a number of other cup-markings; but I can find no account as to whether the ‘foot’ carving possessed ‘toes’, as seen on the impressive Cochno Stone, north of Glasgow. It may have been little more that the petroglyphic ‘feet’ seen on the recently discovered and aptly-named Footprint Stone, or those on the newly rediscovered Witches Stone; but we cannot discount it being larger, like the Footprint Stone of Dunadd. If we could locate an early sketch of the stone, all would be revealed! Sadly, as E.M.H. M’Kerlie (1916) told us,

“this rock was blasted at the time when the government essayed to make the harbour one of great importance”,

several years after the nearby holy well had been re-routed. Fucking idiots! Any further info on this site would be most welcome.

Folklore

The local story that was told about St. Patrick creating these carvings seems to have been described first of all by Andrew Agnew (1864), who wrote:

“Once, when about to revisit his native land, he crossed the Channel at a stride, leaving the mark of his foot distinctly impressed on one of the rocks of the harbour; unfortunately, in making a new jetty, this interesting memento was destroyed.”

(The mention of the jetty would seem to imply that the carving was closer to the sea than the grid-reference cited above.) In another tale, St. Patrick rested his hand onto the same rock and the marks of his hand and fingers were left there. This folklore motif is found across the world. It relates to cosmological creation myths of indigenous spirits and deities in the tribes and cultures who narrate it. In this instance, the myth of St Patrick replaced a much earlier mythic tale of another giant or deity, whose name we have lost. Unless, of course, such petroglyphs were still being carved in Galloway by local people in the 4th-5th centuries.

A further tale of St Patrick, at Portpatrick, replaced a quite obvious shamanistic tale. When he journeyed back from Ireland to Galloway, Agnew again told us:

“Having preached to an assembly on the borders of Ayrshire, the barbarous people seized him, and, amidst shouts of savage glee, struck his head from his body in Glenapp. The good man submitted meekly to the operation; but no sooner was it over than he picked up his own head, and, passing through the crowd, walked back to Portpatrick, but finding no boat ready to sail he boldly breasted the waves and swam across to the opposite shore, where he safely arrived (according to the unanimous testimony of Irishmen innumerable), holding his head between his teeth!”

Legends such this are found in shamanistic pantheons worldwide. Shamans primary renown is their ability to travel and recover from the Lands of the Dead, always journeying into impossible and inhospitable arenas, with tales of being dismembered, beheaded, dying, and returning to life to help the tribe with whatever it was that required such a task (usually a healing function). This story of St Patrick – and many other saints – are mere glosses onto the earlier animistic stories, then abridged as being better, more spiritually mature, more egocentric. But their roots are essentially animistic.

References:

- Agnew, Andrew, The Agnews of Lochnaw: The History of the Hereditary Sheriffs of Galloway, A. & C. Black: Edinburgh 1864.

- Agnew, Andrew, The Hereditary Sheriffs of Galloway – volume 1, David Douglas: Edinburgh 1893.

-

Conway, Daniel, “Holy wells in Wigtonshire,” in Archaeological & Historical Collections Relating to Ayr & Wigton, volume 3, 1882.

- Harper, Malcolm MacLachan, Rambles in Galloway, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1876.

- M’Kerlie, E.M.H., Pilgrim Spots in Galloway, Sands: Edinburgh 1916.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

-

Royal Commission Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in Galloway – County of Wigtown, HMSO: Edinburgh 1912.

- Walker, J. Russel, “‘Holy Wells’ in Scotland,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, vol.17 (New Series, volume 5), 1883.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian