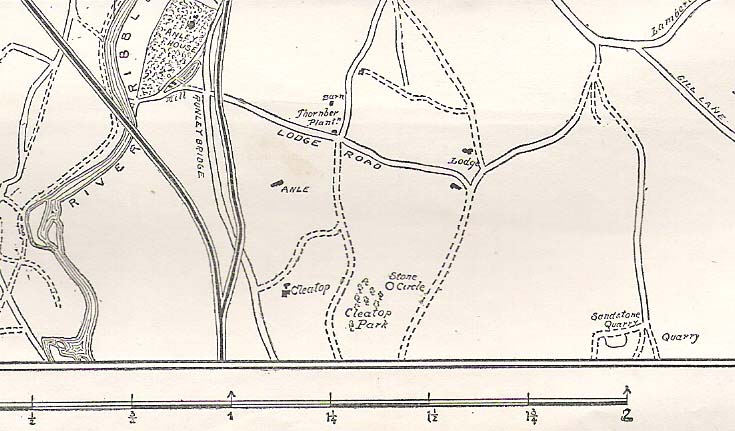

Stone Circle (destroyed): OS grid-reference – SD 821 613

Also known as:

- Druid’s Hill Circle

- Druid’s Circle

Archaeology & History

Not included in any previous archaeological surveys of megalithic rings, this circle of stones was apparently visible from quite a distance away, sitting on the hillside where now there is woodland. It was described by the great Yorkshire historian Harry Speight (1892, 1895), though today it seems that all remains of it have vanished.

An early description of it came after an excursion to the site by local antiquarians, who told that “at Cleatop, about a mile to the south of Settle, are the remains of an ancient stone circle.” (Horsfall-Turner 1888) A few years later, Mr Speight gave us more details of the place, saying:

“A little above Cleatop Farm (near Rathmell)…is Cleatop Wood. Cleatop derives its name from the A.S. cleof, a rocky aclivity; Latin clivus, a bank or slope. Near the northeast side of the wood there was once a very noticeable Druid’s Circle, about 60 feet in diameter; indeed, Mr Thomas Brayshaw of Settle, informs me that within the memory of persons still living, it was so regular and well-defined that one or two gaps caused by the removal of stones could be easily distinguished. The eminence at the rear of the site has, from time immemorial, been known as Druid’s Hill.”

Some years later, that very same local historian Tom Brayshaw (1932) wrote:

“The Ordnance map marks, on the steep slope to the north of Cleatop Wood, ‘site of Stone Circle’. It needs a very keen eye to identify the few stumps that remain today, and it is deplorable that this most interesting monument, after enduring for so many centuries, has been destroyed during the last eighty years. In 1847 a description of the circle, as it then was, was sent to Captain Yolland of the Ordnance Survey.

“”I suppose the circle of stones in Cleatop High Park to be aboriginal British or Druidical remains from the following appearances: the circle is complete and the large stones are set on end, some of them several tons weight. The stones are twelve in number now standing, beside several others that seem to be rolled a short distance, as it is placed on the ascent of a steep hill and commands a beautiful and extensive prospect (more so than any given point of the same altitude in the vicinity). The circle is 36 feet in diameter.”

“A few stones were still standing in 1883. The hill above long bore the name Druids Hill. The Enclosure Acts passed towards the end of the 18th century greatly increased the number of drystone walls in the parish, and it is probable that many old stone monuments were destroyed in making them and in their subsequent repair”.

We have no references of burials or other excavations here to give us any idea of whether human remains had ever been found. It’s an intriguing place in the landscape though…and worthy of further explorations…

References:

- Brayshaw, Thomas, A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick, Halton & Co.: London 1932.

- Horsfall-Turner, J. (ed.), ‘Antiquarian Excursion to Giggleswick and Settle,’ in Yorkshire Folklore Journal, vol.1, T. Harrison: Bingley 1888.

- Speight, Harry, The Craven and Northwest Yorkshire Highlands, Elliott Stock: London 1892.

- Speight, Harry, Tramps and Drives in the Craven Highlands, Elliot Stock: London 1895.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian