Timber Circle: OS Grid Reference – SD 57717 46004

Getting Here

Pretty easy to find, and a nice walk to boot! Head up to Bleasdale Church (worth a look in itself!), keep going up the path north to the aptly named Vicarage Farm. From here you’ll notice a small copse of trees on your left (east) heading to the hills. To those of you who like Predator, “it’s up there – in them trees…!”

Archaeology & History

On my first visit here in the company of John Dixon and other TNA regulars, my first impression was “this is a henge” – and noted subsequently that it’s been described as such by several writers. But the general category given to this fascinating place is a ‘timber circle.’

First discovered at the end of the 19th century and described in considerable detail by Mr Dawkins (1900), this is a gorgeous-looking monument was erected in at once a gentle and tranquil, aswell as an imposing natural setting, at the foot of Fair Snape Fell (to the northwest) and Bleasdale Fell (due southwest). These aspects of the landscape would have had obvious mythic importance to the people who built this ring amongst the trees. A condensed version of Dawkin’s material was described in J. Holden’s (1980) Story of Preston, that outlined this circle as being,

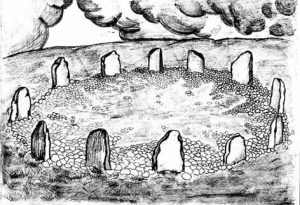

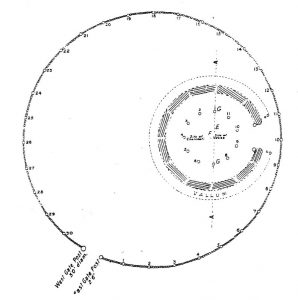

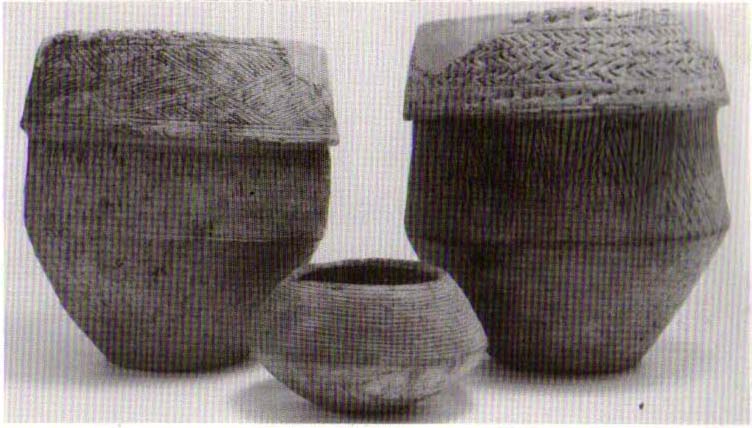

“a centre for religious worship in about 1700 BC. It was made up of a circle of timber posts which enclosed an area 45 metres in diameter. In the centre was a small mound surrounded by a ring of oak posts and a circular ditch. Inside the mound there was a grave that had in it two pottery urns filled with human bones and ashes. Examination of the contents of these urns shows that the bodies were wrapped in linen and burnt on a funeral pyre. A small ‘accessory’ cup was found inside one of the urns and this may have contained food or drink for the afterlife.”

Located within a much larger circular enclosure, the internal Bleasdale ‘henge’ Ring consisted of a small circle of eleven timber posts near the edge of the ditch, and an entrance way to the east, to or from which was an avenue of further wooded posts that led to the edge of the larger enclosure. It gives the impression that this was some sort of avenue along which a ceremonial procession may have took place, strongly suggesting a ritual function. Robert Middleton (1996) told that,

“The post circle and barrow appear to respect each other (in date), whilst the enclosure may be later. The post circle has been dated to around 2200 BC, although the context and reliability of this date is unclear.”

Looking out eastwards from the middle of the internal henge-style ring and through the ‘entrance’ we find an alignment with a large notch on the skyline which, modern folklore ascribes, is where the midwinter sun rises — which is very believable, but I aint seen it proven anywhere yet.

A much greater and full excavation report of this site was written by Raymond Varley (2010), whose essay I urge fellow antiquarians to read.

References:

- Dawkins, W.B., ‘On the Exploration of Prehistoric Sepulchral Remains of the Bronze Age at Bleasdale,’ in Transactions of the Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society, volume 18, 1900.

- Dixon, John, Journeys through Brigantia – volume 8: Forest of Bowland, Aussteiger Publications: Barnoldswick 1992.

- Edwards, Ben, “The History of Archaeology in Lancashire”, in Newman, 1996.

- Gibson, Alex, Stonehenge and Timber Circles, Tempus: Stroud 1998.

- Holden, Jennifer (ed.), The Story of Preston, Harris Museum: Preston n.d. (c.1980)

- Middleton, Robert, “The Neolithic and Bronze Age,” in Newman, 1996.

- Newman, Richard (ed.), The Archaeology of Lancashire, Lancaster University 1996.

- Sever, Linda (ed.), Lancashire’s Sacred Landscape, History Press: Stroud 2010.

- Varley, W.J., ‘The Bleasdale Circle,’ in Antiquaries Journal, volume 18, 1938.

- Varley, Raymond, “The Bleasdale Bronze Age Timber Circle,” in Lancashire History Quarterly, 2010.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian