Standing Stone: OS Grid reference – SE 15196 54722

From Blubberhouses church by the crossroads, walk up the slope (south) as if you’re going to Askwith, for 100 yards or so, taking the track and footpath past the Manor House and onto the moor. Once you hit the moorland proper, take the footpath that bears left going down into heather and keep going till you hit the dead straight Roman Road path running west onto Blubberhouses Moor. Carry along the Roman Road for about 200 yards as though you are going towards the Eagle Stone, and looking right (if you squint) you can just make out a small pimple on the top of the moors about a quarter of a mile away. That is where you are heading (be warned – it is boggy getting there).

Archaeology and History

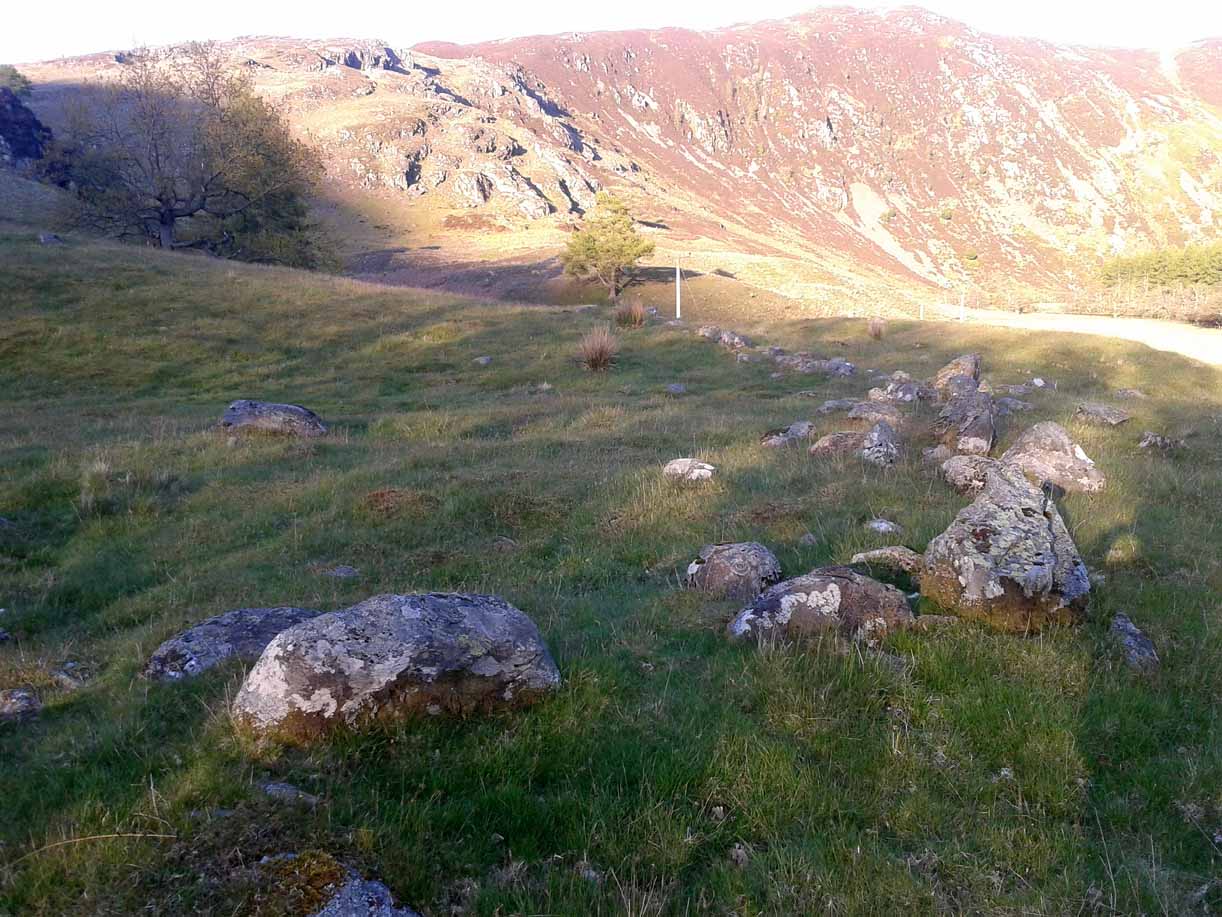

Discovered (or rather ‘noticed’) by James Turner and James Elkington in July 2016 (hence the name James Stone), this standing stone is of an indeterminable age – although it does look ancient. Standing more than 5 feet tall, and in the middle of nowhere, it is fairly difficult to get to unless you want to get wet feet. It is situated very close to a small and unexcavated prehistoric settlement and we could find no physical evidence of any tracks nearby (although Google Earth does show what looks like one or two very short, faint tracks near the stone, which is the old ‘Benty Gate’ track).

It could be a boundary stone, although doubtful – it has a feel to it that says it is prehistoric, although this is just guesswork on our part. I can find no reference to it in Cowlings Rombalds Way (1946) and there seems nothing about it in either of William Grainge’s (1871; 1895) detailed history works of the region.

At first we thought it unlikely to be a new find, however the stone is difficult to see from the Roman Road (I had been up here dozens of times before I noticed it) and seeing that people rarely go up here anyway, and it is relatively difficult terrain getting to it, it is not surprising that no one has bothered visiting it. It would take someone who is quite keen on megaliths to want to examine it and it is well off any tracks.

Having said that, it is a nice find and it could be linked in some way with the small unexcavated settlement nearby, or possibly the large Green Plain settlement nearly a mile away. Well worth a visit…bring your wellies!

References:

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Grainge, William, The History and Topography of Harrogate and the Forest of Knaresborough, John Russell Smith: London 1871.

- Grainge, William, The History and Topography of the Townships of Little Timble, Great Timble and the Hamlet of Snowden, William Walker: Otley 1895.

© James Elkington, The Northern Antiquarian