Healing Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 3442 2686

Also Known as:

- St. Swithin’s Well

Archaeology & History

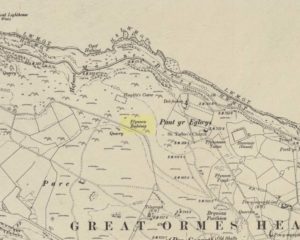

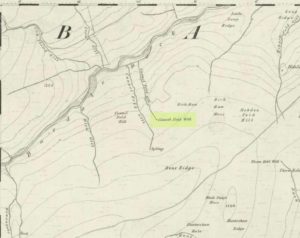

Swithins Well on 1854 map

Highlighted in the fields on the south-side of Rothwell village on the 1854 OS-map, Swithin’s Well was, according to historian Andrea Smith (1982), previously known as a holy well, dedicated to the obscure Saxon saint of the same name. Although no ‘well’ relating to St Swithin comes from any early texts, the field and farmhouse of ‘Swithins’ were cited in records from the Cartulary of Nostell Priory in 1270 CE; then subsequently in a variety of records throughout the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. According to Miss Smith (1982),

“The first recording of St Swithin’s Well, Rothwell…was on an estate map of 1792 (‘Plan of St. Clement’s lands in the parish of Rothwell in the County of York, two-third part of the tithes of corn and grain of which belong to the King in right of His Ducky of Lancaster’, PB), and the field-names arising from it—Swithin’s, Swithin’s Barn, Swithin’s Lane Close—serve to give an indication of the well’s past importance as a local landmark.”

When she visited the site around 1980, she reported finding,

“several wet patches running in a line westwards downhill, but the farmer’s wife seemed certain that this was a broken drain and nothing else could be seen in that field or neighbouring ones, which could have been the well.”

Very recently, the Wakefield pagan and antiquarian Steve Jones went to see if the well or any remains of it could still be seen and told us:

“We went looking for the well down a footpath but it was obviously filled in when a colliery was nearby in the early 20th century and (there is) no trace of any spring now.”

Another one’s bitten the dust, as they say…..

But we must note that the grand place-name authority, A.H. Smith (1962) found no references to St. Swithin here and instead suggested the name derived from the old Norse word, sviðinn, ‘land cleared by burning’, which is echoed in the old local dialect word swithen, ‘moorland cleared by burning’ (Smith 1956), and similarly echoed in Joseph Wright’s (1905) magnum opus, where—along with meaning ‘crooked, warped’—it means “to burn, superficially, as heather, wool, etc.” There is also a complete lack of any mention to the saintly aspects of this place in John Batty’s (1877) primary history book on Rothwell parish, and yet he cites numerous other springs and wells in the region that have fallen out of history.

References:

- Batty, John, The History of Rothwell, privately printed: Rothwell 1877.

- Jones, Steve, Personal communication, Facebook 27.08.2018.

- Rattue, James, “The Wells of St Swithun,” in Source, Summer 1995.

- Smith, Andrea, “Holy Wells Around Leeds, Bradford & Pontefract,” in Wakefield Historical Journal 9, 1982.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1961.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Name Elements – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1956.

- Wright, Joseph, English Dialect Dictionary – volume 5, Henry Frowde: Oxford 1905.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Steve Jones of Wakefield for his informing us about the status of this site.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian