Stone Circle: OS Grid Reference – NN 57699 32805

Also Known as:

- Killin P1/3 (Thom)

Getting Here

At the pub by the bridge which crosses the Falls of Dochart (aptly called the ‘Falls of Dochart Inn’), walk downstream following the dirt-track which runs parallel with a section of the river for a good 5-600 yards. In the field that appears on your right, watch out for the rise of the stones as you approach the large gates which take you into the ground of Kinnell House. You can climb over the gate just into the field and go straight to the stones.

Archaeology & History

Found on the field called Kinnell Park in the grounds of Kinnell House, less than a mile out of Killin, this is a well-preserved site consisting of six stones. It appears to have been described first of all by Thomas Pennant in 1772, in the same breath as the megalithic remains at Lawers on the other side of Loch Tay. Pennant wrote:

“In going through Laurs observe a Druidical circle; less complete indeed than one, that should have been mentioned before, at Kinnel, a little southwest of Killin; which consists of six vast stones, placed equidistant from each other.”

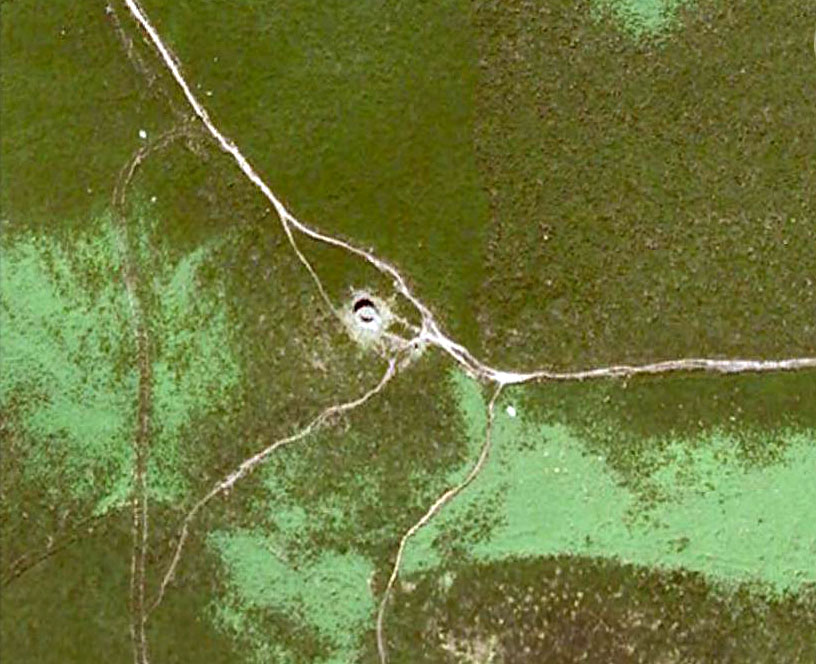

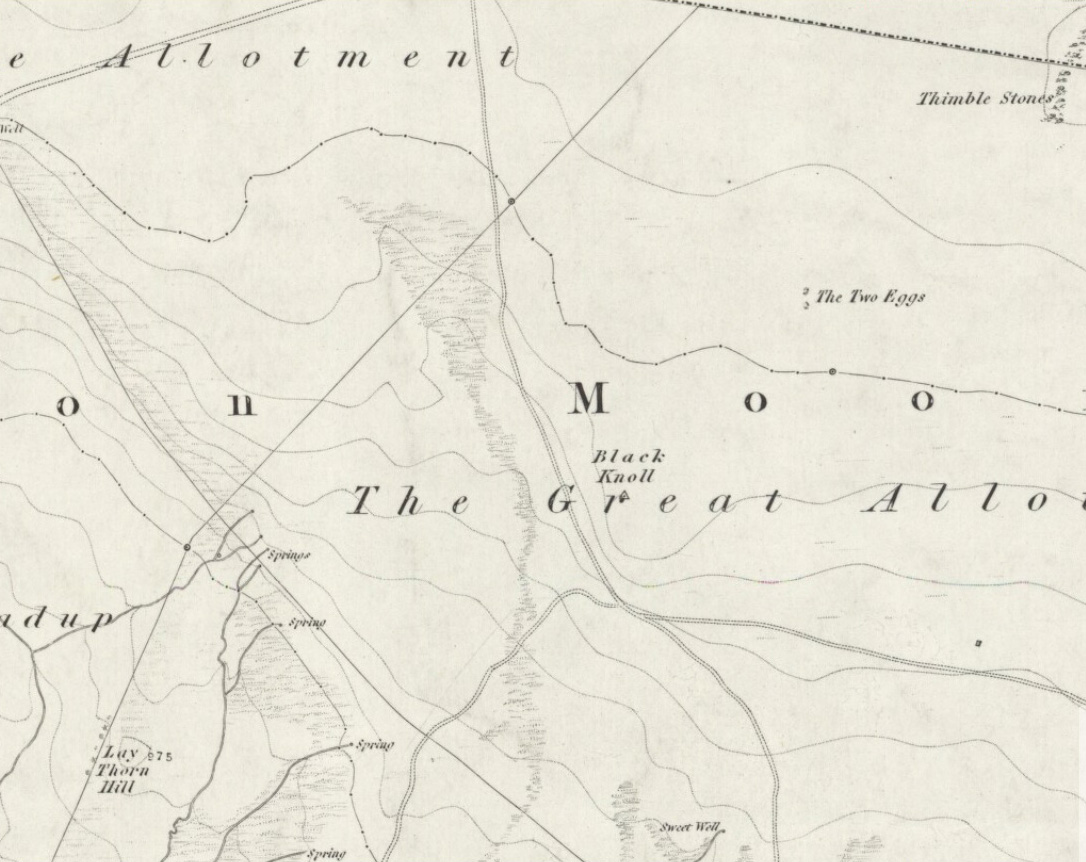

It would seem that the site has changed little since Pennant’s visit. Sitting on a reasonably level grassy plain, the hills rise and surround the small ring of stones, with the lower horizons running along the south. Due west (equinox) we have the large pyramidal hill of Meall Clachach; whilst to the north are the legendary hills of Creag na Cailleach and Ben Lawers, each with their own rich mythic archaeological legacies. Legendary stones and wells are also close by, some with rites still enacted by old local people keeping truly ancient traditions alive.

The first detailed archaeological survey of the Kinnell site was done by Fred Coles and published in 1910. It has yet to be superseded. Mr Coles wrote:

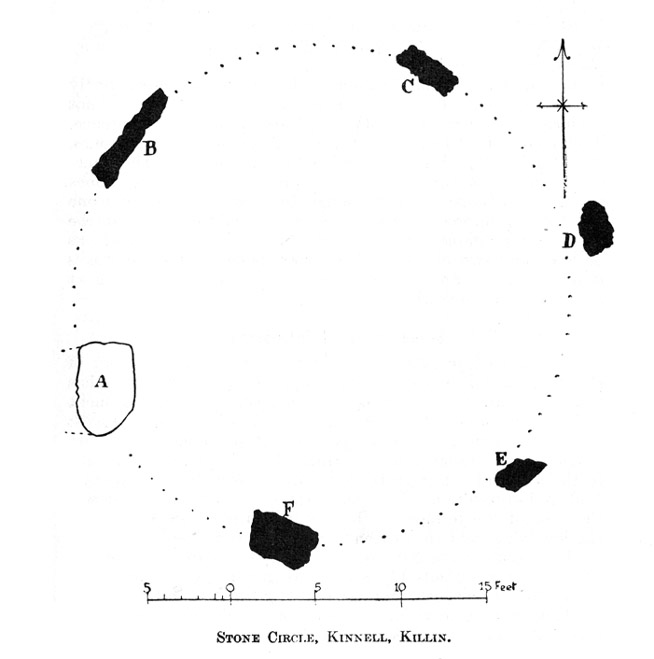

“Taking the Stones in the usual order…I here give their dimensions and characteristics: Stone A, 6 feet 3 inches high, springs from an oblong base which girths 11 feet 4 inches, to a rough irregular top; Stone B leans forward towards the centre of the Circle, and measures along its sloping back 6 feet 9 inches, the present height from the ground to its upper edge being 4 feet. It is of smooth garnetiferous schist, and free from the deep fissures and rifts so common in these Stones. Stone C, a very rectangular but narrow block of schist, has a 15 Feet-girth at the base of 9 feet, but tapers up from both ends to a pyramidal summit, 5 feet 4 inches above ground. Its inner face is over 6 feet in breadth. Stone D, 4 feet 6 inches high, is a broad, flat-topped, very massive block, measuring 9 feet 5 inches round the base, but near the middle of its height 11 feet 2 inches. Stone E, the shortest of the group, is only 4 feet high, has a rough, uneven top, and a basal girth of 8 feet 11 inches. Stone F, the tallest, measures 6 feet 4 inches in height, but in girth only 7 feet 3 inches. It is very rough, vertically fissured in many places, and full of white quartz veins.

“Neat, well-defined, and comparatively small as this Circle is, it is to be noticed that the positions of the Stones do not conform to perfect regularity as points on the circumference. On working out the plan, the measurements prove that a diameter of 29 feet exactly bisects three of the erect Stones, B, C, and F, but leaves the other two untouched. The interspaces of the settings are not all quite equal, a space of 14 feet 8 inches dividing the centres respectively of F and A, A and B, F and E, and E and T); but between D and C it is 13 feet 8 inches, and between 0 and B I S feet 5 inches. Yet, the Stones stand proportionally near enough to each other to give one a satisfying impression that these six megaliths represent the group in its completeness, and that there were no smaller blocks between any two of them. The space enclosed by these stones is quite smooth and level, bearing no indication of having at any time been disturbed.”

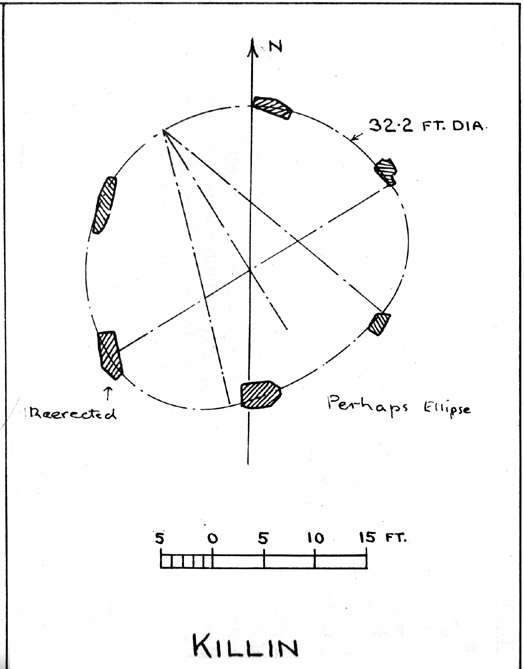

Many years later, the late great Alexander Thom came here and, with his geometric perspective, gave a more precise ground-plan and lay-out. Thom (1980) defined the site as a “Type B flattened circle, or possible ellipse,” with a perimeter of 35 megalithic yards and diameter of 11.8 MY. Aubrey Burl’s commentary described Kinnell as:

“Six stones of schist stand evenly spaced on the circumference of an ellipse 32ft 7in x 27ft 5in (9.9 x 8.4m) in diameter. The stones are graded in height towards the SW where the two tallest are over 6ft (1.8m) high.”

One of the upright stones was said by Hugh MacMillan (1884) to have had cup-markings on it in the 19th century, when he told of the circle possessing “some seven or eight tall massive stones, with a few faint cup-marks on one of them.” But these appear to have faded, or were cut into the one of the missing stones.

Folklore

Close to the Kinnell circle could once be found a curious large boulder, covered in moss, but with a large cavity in which water gathered. Local lore ascribed the rock to actually be a well, as it was known as ‘The Well of the Whooping-Cough’, or Fuaran na Druidh Chasad, measuring some eight feet long and five feet high. Local people visited the site to be cured of the said disease, but Hugh MacMillan also suggested that the miraculous well-in-the-stone was connected with ancient rituals once enacted at the Kinnell circle, saying:

” it is a reasonable supposition that the Fountain of the Whooping-Cough may have had some connection in ancient times with this prehistoric structure in its immediate neighbourhood…”

He may have been right!

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany, New Haven & London 1995.

- Coles, Fred R., “Report on Stone Circles Surveyed in Perthshire (Aberfeldy District),” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 44, 1910.

- Fraser, Duncan, Highland Perthshire, Standard Press: Montrose 1973.

- Gillies, William A., In Famed Breadalbane, Munro Press: Perth 1938.

- McKerracher, Archie, Perthshire in History and Legend, John Donald: Edinburgh 1988.

- MacMillan, Hugh, ‘Notice of Two Boulders having Rain-Filled Cavities on the Shores of Loch Tay, Formerly Associated with the Cure of Disease,’ in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 18, 1884.

- Pennant, Thomas, A Tour in Scotland, 1772 – Part 2, Benjamin White: London 1776.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Stirling District, Central Region, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1979.

- Thom, A., Thom, A.S. & Burl, H.A.W., Megalithic Rings, BAR: Oxford 1980.

- Wheater, Hilary, Killin to Glencoe, Appin Publications: Aberfeldy 1982.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian