Tomb: OS Grid Reference – NS 8848 9754

Also Known as:

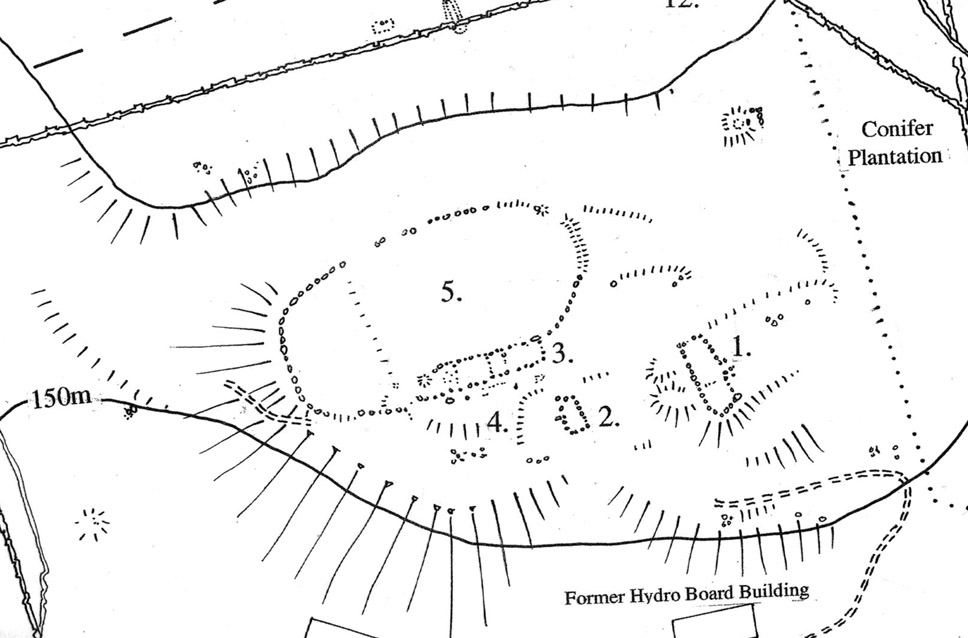

From the main street through Alva, between the Co-op and the corner shop, go up the small road at the side of the Johnstone Arms Hotel (Brook Street) and, at the small crossroads, straight across as if following the sign to the golf course. Stay along the track parallel with the Alva Burn waters and as you go into the trees a hundred yards or so along, to your left is a disused quarry, with a couple of plaques telling you its brief history. This is the spot!

Archaeology & History

This is a truly fascinating site for a number of reasons. Sadly, we can no longer see what had been here for oh so many thousands of years thanks, as usual, to the industrialists destroying the land here. Although in this case, without them we’d be unaware of its very existence. Additionally, there is a twist to the industrial’s find, which seems to have stopped further quarrying by some local people….

Listed in the relative Royal Commission accounts (1933; 1978), without comments, the tale is a simple one, but was narrated in some detail by J.G. Callander (1914) in Scotland’s prodigious Society of Antiquaries journal. During some quarrying operations over the Christmas period of 1912, James Murdoch “uncovered the remains of a human skeleton which had been buried in a natural cavity in the rock.” Three weeks later, local police officer George Donald and Dr W.L. Cunningham of Alva, accompanied Mr Callander to the site and made a detailed assessment of what had been found. He wrote:

“The quarry in which the grave was found is situated at the mouth of Alva Glen, a few yards distant from the right bank of the burn which flows through it. The body had been placed in a cavity or rock shelter in the face of the cliff, about 40 feet from the base, and about 200 feet above sea-level, and a rough, curved wall of dry-stone building, about 1 foot in thickness, had been built across the opening, which faced the east, the ends of the wall being still in situ when I visited the site. The space enclosed measured about 4 feet 6 inches from north to south, and about 5 feet from east to west. Subsequent to the burial the whole face of the rock and the walling had been covered, to a thickness of probably some 6 feet, by soil and detritus washed down from the hill face above. The greater part of the floor of the cavity was formed of clean, broken, angular stones, but the space on which the body was placed had been covered with a thin layer of soil preparatory to the burial. No charcoal or charred wood, which is so often seen in prehistoric graves, was found in this deposit. The skull lay in the north end of the grave, on its right side, facing the rock to the west, the vertebrae and ribs followed a line to the south, and the nether limbs were inclined towards the interior of the cavity. The whole face, including all the teeth and the lower jaw, was a-wanting. Apparently the body had been placed in a flexed position, half on its side and half on its back. Nothing else was found in the grave but a quantity of snail shells, probably twenty or thirty, which were nearly all broken, the few complete examples being in a very fragile condition.

“Elsewhere it has been stated that these formed a necklace, but while they were strewn out in front of the skeleton for a distance of over 3 feet, none of them showed any signs of artificial perforation. The species of Helixis is probably hortensis, the common garden snail.”

Mr Callander then included a lengthy description of the body itself, some of whose bones were fractured. He told that a certain

“Professor Bryce states that the skeleton is that of a dwarf of about 4 feet 2 inches in stature. The epiphyses are all fully united, although the line of union is visible on the surface at some points. Growth must therefore have been completed, and the person must have been, if the union of the epiphyses of the long bones had pursued its normal course, over twenty-one years of age…”

Regarding the sex of the dwarf, Mr Bryce wasn’t 100% certain, but told:

“The calvaria shows the general characters of a female skull, but it cannot be stated definitely that the individual was a woman, because the cranial characters are such as might have been present in a dwarf of the male sex. The calvaria is of moderate size, and is well formed.”

Bryce concluded as a whole that this person was in reasonably good health and, from the condition of the bones, showed “there was no evidence of the disease known as rickets.” In his final remarks he told:

“The general conclusions to which a careful examination of the skeleton leads, is that we have here to do, not with a representative of a dwarfish race, but with an individual who from premature union of the epiphyses was to a remarkable degree stunted in growth. The condition is a well-known one, and the class of dwarfs, in which this individual must be included, is well recognised.”

The exact spot of the tomb appears to have been destroyed, or at the very least is certainly covered over and no longer visible. The section of the quarry looking east, into which the tomb was built, is all-but gone and no initial evidence prevails to show its exact location. However, it would seem from the description to have been close to the tops of the tree-line, perhaps giving a clear view to the rising sun in the east. Perhaps…

The position of this tomb, enclosed high up in the cliffs, hidden away at the entrance to the deeply cut ravine of the Alva Glen, is intriguing in that it is a rarity. Ravines like this are always peopled by olde spirits in animistic tribal traditions — and this dangerous glen with its fast waters and high falls would have been no different, especially to the Pictish people who we know were still here even after the Romans had buggered off. Is it possible that this figure was a guardian to the Glen itself, a medicine woman or shaman, whose very Glen was her home? We know from traditional accounts in many of the North American tribes that dwarves were accessories to the spirit worlds, and some were shamans. (Park 1938) In northern and central European lore, these small people are “the mysterious craftsmen-priests of early civilizations.” (Motz 1987) Whilst in Scottish lowland lore, the ‘Brown Man of the Muirs’ was a dwarfish creature described by Briggs (1979) as “a guardian spirit of wild beasts”, or watered-down shaman figure. There is more to this burial than meets the eye of dry academia…

Folklore

The Alva Glen—in addition to being beautiful and home to the Ladies Well—was long known to be one of many places in the Ochils that were peopled by the faerie folk. (Fergusson 1912) Local people still say this place is haunted by the spirit of a dangerous witch called Jenny Mutton.

It’s worth reiterating the words of Mr Callander (1914) regarding the finding and subsequent death of the man who uncovered this fascinating tomb, as some folk (then as now) think his demise was as inevitable as the man who planned on building turbines in Glen Cailleach:

“On the 24th December last, while quarrying stone for road metal in a quarry at the foot of the Ochils, at Alva, James Murdoch uncovered the remains of a human skeleton which had been buried in a natural cavity in the rock. Two days later he was killed at the same spot by the fall of a mass of overhanging rock, a tragic sequel, which not long ago would have been considered a judgement on him for disturbing the dead.”

References:

- Briggs, Katherine M., A Dictionary of Fairies, Penguin: Harmondsworth 1979.

- Callander, J. Graham, “Of a Prehistoric Burial at Alva, Clackmannanshire,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 48, 1914.

- Corbett, L., et al., The Ochil Hills, Forth Naturalist & Historian 1994.

- Drummond, A.L., “The Prehistory and Prehistoric Remains of the Hillfoots and Neighbouring District”, in Transactions Stirling Natural History & Antiquarian Society, volume 59, 1937.

- Fergusson, R. Menzies, The Ochil Fairy Tales, David Nutt: London 1912.

- Gimbutas, Marija, “Slavic Religion,” in Encyclopedia of Religion – volume 13 (editor M. Eliade), MacMillan: New York 1987.

- Motz, Lotte, “Dvergar,” in Encyclopedia of Religion – volume 4 (editor M. Eliade), MacMillan: New York 1987.

- Park, Willard Z., Shamanism in Western North America: A Study in Cultural Relationships, Evanston: Chicago 1938.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Inventory of Monuments and Constructions in the Counties of Fife, Kinross and Clackmannan, HMSO: Edinburgh 1933.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, The Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Clackmannan District and Falkirk District, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1978.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian