A prehistoric ‘fort’ with a long history behind it, with recent excavations finding burial and settlement remains from the Bronze- and Iron Ages. The following article about this impressive archaeological site was written by Barry Raftery’s in an early edition of Antiquity journal (1970), following excavation work here. He wrote:

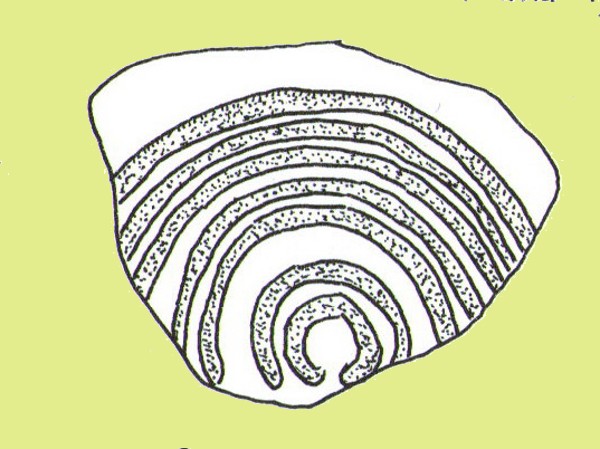

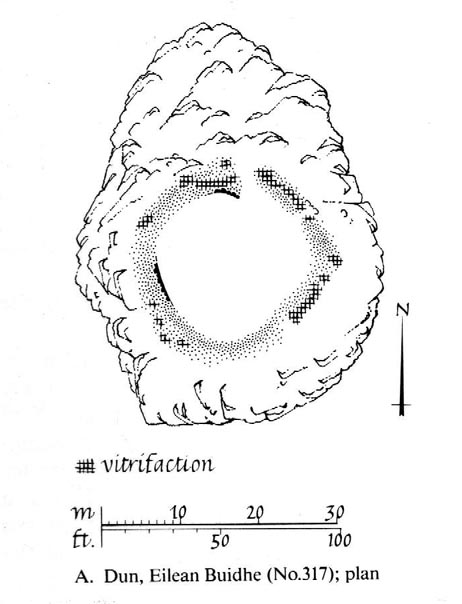

“Rathgall is a large and imposing hillfort situated on the end of a long ridge some 6km east of Tullow, Co. Carlow. It is sited impressively and commands a fine view on all sides. The defences of the fort comprise four roughly circular, concentric ramparts. The three outer banks, though largely overgrown, appear to be of earth faced with stone; the inner one is built entirely of granite boulders, many of considerable size. The fort covers some 18 acres (c. 7 hectares); its overall diameter is about 310m. (Orpen 1911; 1913)

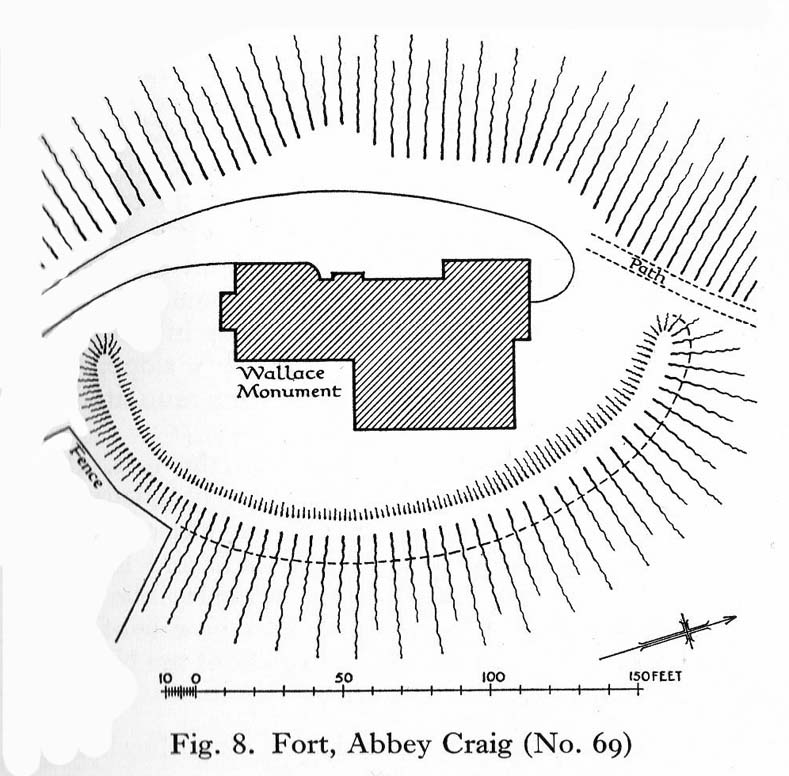

“Excavation in 1969 was confined, with the exception of one short trench, to the inner enclosure. This is surrounded by the granite wall, dry-built and of poor quality. It is made up of a series of straight lengths so that, though superficially the enclosure appears to be circular, it is in fact polygonal. The entrance is a simple break on the western side. The wall varies in thickness from 7m in the southeast, to 1.5m in the north, though the reason is not immediately clear. In height the wall varies from 2m to 2.5m. The minimum internal dimensions of the enclosure are 44m and 46m.

“About one-quarter of the enclosure was excavated in the northeastern quadrant. A trench 2m wide and 20m long outside the wall and running into the interior was begun and this demonstrated the existence of occupation outside the wall.

“The first season’s excavation suggests the presence of at least three main phases of occupation on the site — Late Bronze Age, early Iron Age and Medieval. The relatively thin soil covering on the site does not as yet allow the periods to be clearly defined stratigraphically.

“About 1500 objects came to light, over 1000 of them being pot-sherds. The great majority belong to the Early Iron Age phase of occupation, apparently the period of densest settlement on the site. As well as the remains of circular and rectangular structures, the excavation also revealed a number of very large hearths and a bank-and-ditch enclosure hitherto quite unsuspected.

“This latter feature partly underlay the granite wall. The ditch had been filled in and the bank denuded before the construction of the wall. The latter averaged about 50cm high and lay outside the ditch, which was dug carefully to a V-shaped section. In width it varied from 1.5 to 3.5m at its edge and in depth from 75cm to 1.1m

“Bank and ditch enclosed an area about 35m in diameter. So far no entrance to this enclosure has been distinguished, though there appears to be a gap in the south-east which may be an original opening. It is noticeable that the bank runs, without a break, straight across the entrance to the stone enclosure, further emphasizing the lack of structural connection between the two features.

“The relationship of either of these enclosures to the outer lines of defence is not clear and so elucidation of this problem must await further excavation. It seems, however, that the granite wall is a late feature and is probably of medieval date. The massive outer ramparts, on the other hand, are more likely to belong to the Early Iron Age occupation of Rathgall.

“Over the whole area so far excavated indications of rectangular houses were frequent. The walls of these houses were formed of timber posts, generally of no great size; they were set usually singly but sometimes in paris, in bedding trenches 30 to 40cm wide. The upright posts presumably formed the framework of wattle-and-daub constructions. There appears to have been extensive rebuilding, so that the plans are greatly confused and not always easy to interpret. The houses were quite large: one of them was as much as 7.5m in length.

“These houses belong to the latest phase of occupation on the site and appear to be contemporary with the construction of the granite wall. They were built on top of the fill of the ditch and were confined by the wall: there is no indication anywhere of house foundations running underneath the wall. Green-glazed sherd from the fill of the bedding trenches suggests a 13th-century date for these houses and a late 13th-century silver coin points in the same direction.

“A circular bedding trench, apparently concentric with the large V-shaped ditch, was found in the centre of the stone-walled enclosure. One-quarter of the bedding trench was exposed in the 1969 excavations. In section it is roughly U-shaped and is 25cm wide and 30-35cm deep. It encloses a space about 18m in diameter. Its outer edge is for the most part lined with packing stones of medium size. One metre inside this bedding trench and running concentrically with it for about one-third of the excavated arc there is a second bedding trench of similar type. Whether these bedding trenches represent the remains of a large timber house of whether they were for a timber stockade is uncertain; further excavation may provide the answer to this problem. As regards relative dating, however, it is clear that the circular structure, whatever it was, was earlier than the rectangular houses, for the bedding trenches of the latter lay above the trench for the former. As well, some sherds of coarse ware of a date appreciably earlier than medieval times were found in the fill of the circular trenches.

“In turn, a huge oval hearth was found beneath the circular structure. The hearth consisted of a steep-sided, flat-bottomed pit, 3.1m long and 1.5m wide, dug into the yellow subsoil. A large quantity of black, burnt material came from the hearth and there appeared to be three main phases of use, each separated from the other by a layer of rough cobbling. The hearth also produced sherds of coarse pottery, including two decorated fragments. The decoration takes the form of one sherd of a row of finger-nail impressions and on the other a row of simple nicks in the edge of the rim.

“Large hearths of this type are, indeed, a feature of the site as a whole. Five in all have so far come to light: one, especially elaborate, consisted of a large rectangular pit, 2.85m by 1.2m, dug 40cm into the subsoil. At each corner there was a circular pit; two of these pits look like post-holes, the other two appear to be much too large to have served such a purpose. All the hearths have produced coarse pottery and can thus be placed in their relative chronological position, though as yet none appears to be related specifically to any single structure on the site. It may be that these were open-air hearths, covered by some sort of canopy.

“In addition to the hearths, the rectangular houses, the circular structure and the ditch and bank, a large number of post-holes were found. Some of these were large, some small, but in no case could any positive pattern be established.

“The importance of the structural remains on the site is equalled by the significance of the material recovered. The finds from the medieval period have already been referred to and the rectangular houses with which they were associated. Before this there appears to have been a lengthy period when the site was not occupied. The occupation before the beginning of this break appears to have been intensive. It is characterized by large quantities of very coarse pottery. This distinctive ware may be termed Freestone Hill Ware after the importance of the hillfort site of that name in County Kilkenny where the pottery was first isolated. At this site it was associated with Roman bronzes of the 4th century AD and with a coin of Constantine II (Raftery, 1969).

“The sherds represent coarse, flat-bottomed, bucket-shaped pots, usually of a reddish, crumbly ware with very large grits. Distinctive rims are characteristic: they are rounded, flat, T-shaped or internally bevelled. At Freestone Hill a striking feature was the presence on many of the rim sherds of a row of small perforations; similar perforated rims are included in the Rathgall material. In addition to the pottery, blue glass beads, bones, spindle whorls, portions of a lignite bracelet and many other objects of normal domestic refuse came to light. A complete saddle quern was also found. The most interesting of the Early Iron Age finds, however, was a small tinned strap-mount, beautifully decorated with a combination of openwork and incised curvilinear ornament of sub-La Tene type. The art on this object has much in common with that on a bronze mount found at Freestone Hill and both appear to have a vital bearing on the transition from the true La Tene art of pre-christian times to the great flowering of art in Early Historic Ireland.

“Both at Freestone Hill and at Rathgall these decorated bronzes were associated with coarse pottery of identical type. The pottery at the former site was dated to the mid-4th century and there, at least, the date is hardly in doubt. It is possible to suggest a similar dating for the Wicklow material. Coarse pottery of this type may, however, have had a fairly long life and indeed Freestone Hill may give but a central date for the group.

“Several points of some significance in relation to this pottery must be stressed. Firstly, no excavated ring fort (rath) has ever produced this kind of ware — indeed, it is absent from any excavated site of the Early Historic Period in Ireland. On the other hand, it is found increasingly in hillforts — to such an extent in fact, that it appears more and more to be basically a hillfort phenomenon. Apart from the two sites referred to above, similar coarse sherds come from the hillforts at Clogher, Co. Tyrone, Emain Macaha, Co. Armagh, Downpatrick, Co. Down, and possibly also from Dunbeg in the same county. In the present state of our knowledge therefore, it seems that Freestone Hill Ware may be regarded as characteristic of Irish hillforts: there is as yet no evidence for its continuation beyond the middle of the 1st millenium AD.

“The origins and ancestry of Freestone Hill Ware are matters which can hardly be discussed here, but pottery of this type without the perforated rims, may go back to pre-christian centuries. Indeed, the indications at Emain Macha tend to confirm this possibility and Freestone Hill Ware may well have had its origins in the so-called Flat-rimmed wares of the Late Bronze Age in Ireland.

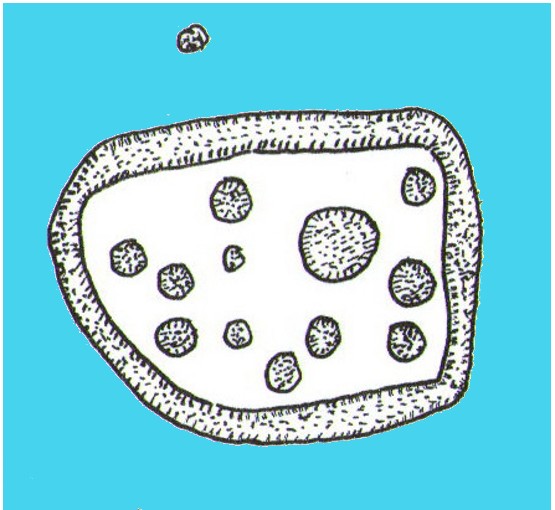

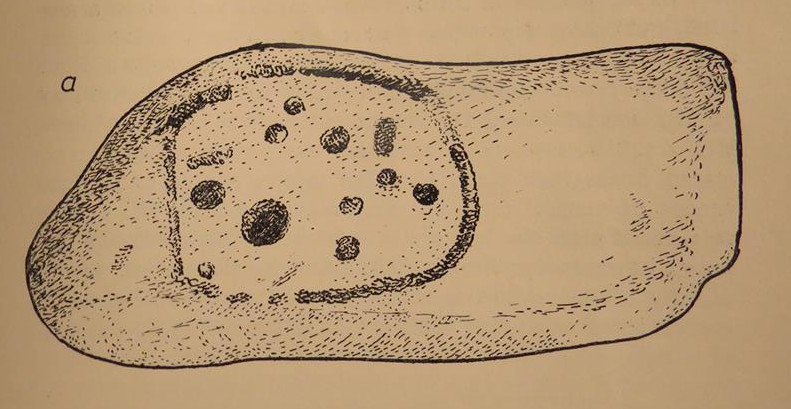

“This problem seems very real at Rathgall, since here are strong indications of Late Bronze Age activity. This is the third of the three phases of occupation of the site. Mould fragments of clay were recovered which were used in the manufacture of objects of Late Bronze Age type — swords, possibly spears and socketed implements with a rope moulding round the mouth of the socket. The relationship of these fragments to any of the structures which were uncovered during the excavation is not clear. In fact, apart from the mould fragments (and possibly the saddle quern) there is nothing else which can with certainty be assigned to a late Bronze Age context. Some of the mould fragments came from the immediate vicinity of one of the large hearth, some from the fill of the ditch, and from the ditch also came the saddle quern.

“The presence of the mould fragments in the ditch is complicated by the discovery, in the very bottom, of fragments of pottery which seem to belong to that class known as Cordoned Ware which occurs in southwestern Britain and northwestern France in the centuries before and just after the birth of Christ. It would seem then either that the mould fragments found their way into the ditch during an in-filling operation which took place at a time subsequent to the original Late Bronze Age occupation of the site, or alternatively that the pieces are contemporary with the Cordoned Ware, thereby suggesting a remarkable continuity of Late Bronze Age types in Ireland.

“At all events the construction of the ditch can be dated with reasonable certainty to the period of the Cordoned pottery. Pottery of this type has never before been found in Ireland and its implications regarding Irish/British and Irish/Continental connections in the Early Iron Age — as well as having an important bearing on the development of the Irish hillfort — are considerable.

“The question of the date of the hearths is as yet a matter of some doubt. It has already been pointed out that in one area a hearth was overlain by both the circular enclosure and the much later rectangular structures. This hearth at least belongs to any early phase of the occupation of the site and since all the five hearths so far revealed by excavation are not apparently associated with specific structures and have several points in common, such as size and details of construction, it seems reasonable to suggest that they may be broadly contemporary.

“All the hearths produced coarse ware and it therefore seems to be of prime importance to be able to distinguish between the Freestone Hill type of pottery of the Early Iron Age and the pottery to which the name Flat-rimmed Ware has been given and which is dated to the Late Bronze Age. It may be that both are in the same developmental tradition and it is hoped that further work on the hillfort at Rathgall will help to elucidate the problem involved.”