Sacred Tree: OS Grid Reference – NN 9621 1587

Just off the A9 between Stirling and Perth is Aberuthven village. Down the Main Street and just south of the village, turn west along Mennieburn Road. A half-mile on, just past Ballielands farm, you reach the woods. Keep along the road for another half-mile, close to where the trees end and go through the gate where all the rocks are piled. Walk up to the tree-line 50 yards away and follow it along the line of the fence east, til it turns down the slope. Naathen – over the barbed fence here, close to the corner, about 10 yards in, is the tree in question…

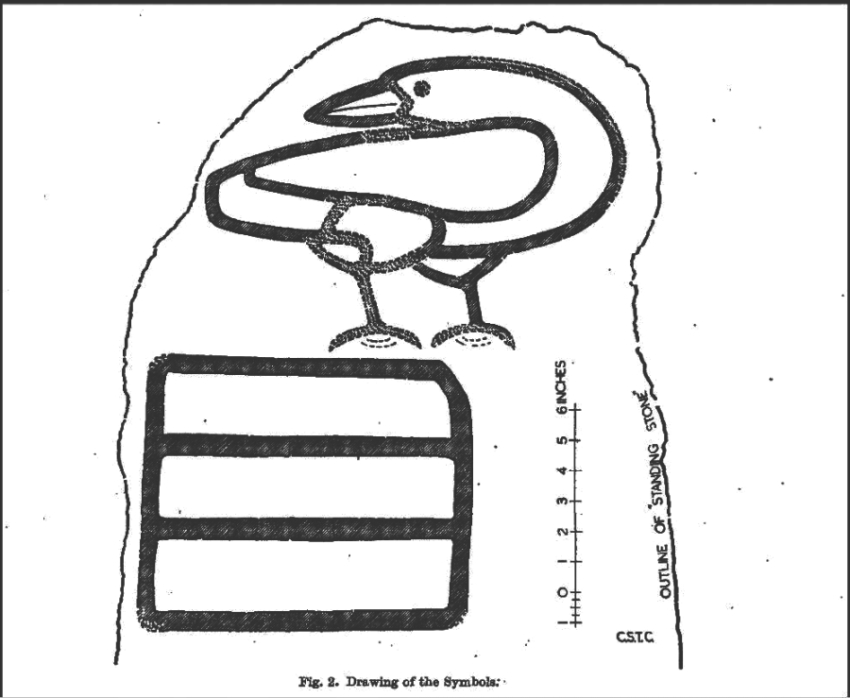

Archaeology & History

Laid down on the peaty earth, fallen perhaps fifty years ago or more, are the dying remains of this all-but forgotten Witch Tree. To those of you who may strive to locate it—amidst the dense eye-poking branches of the surrounding Pinus monoculture—the curious feature on this dying tree are a number of old iron steps or pegs, from just above the large upturned roots. About a dozen of them were hammered into the trunk some 100 years or more ago and, were it to stand upright again, reach perhaps 30 feet high or more. These iron pegs give the impression of them being used to help someone climb the tree when it was upright; but their position on the trunk and the small distance between some of them shows that this was not their intention. Their purpose on the tree is a puzzle to us (does anyone have any ideas?).

The fallen trunk has broken into two main sections, each with iron pegs in them. The very top of the tree has almost completely been eaten back into the Earth. Unfortunately too, all the bark has completely rotted away and so identifying the species of the tree is difficult (though I’m sure there are some hardcore botanists out there who’d be able to enlighten us). The possibility that the early map-reference related to a Wych-elm (Ulmus glabra) cannot be discounted, although this would be most unusual for Ordnance officers to mistake such a tree species with a ‘witch’. Local dialect, of course, may have been a contributing factor; but in Wilson’s (1915) detailed analysis of the regional dialect of this very area, “wych elm” for witches does not occur. Added to this is the fact that the indigenous woodland that remains here is an almost glowing birchwood (Betula pendula) in which profusions of the shaman’s plant, Amanita muscaria, exceed. There were no wych elms hereby.

The tree was noted by the Ordnance Survey team in 1899 and was published on their maps two years later, but we know nothing more about it. Hence, we publish it here in the hope that someone might be able top throw some light on this historical site.

Folklore

We can find nothing specific to the tree; but all around the area there are a plethora of tales relating to witches (Hunter 1896; Reid 1899)—some with supposedly ‘factual’ written accounts (though much of them are make-believe projections of a very corrupt Church), whilst others are oral traditions with more realistic tendencies as they are rich in animistic content. One of them talks of the great mythical witch called Kate McNiven, generally of Monzie, nearly 8 miles northwest of here. She came to possess a magickal ring which ended up being handed to the owners of Aberuthven House, not far from the Witch Tree, as their associates had tried to save her from the crazies in the Church. This may have been one of the places where she and other witches met in bygone centuries, to avoid the psychiatric prying eyes of christendom.

Until the emergence of the Industrialists, trees possessed a truly fascinating and important history, integral to that of humans: not as ‘commodities’ in the modern depersonalized religion of Economics, but (amongst other things) as moot points—gathering places where tribal meetings, council meetings and courts were held. (Gomme 1880) The practice occurred all over the world and trees were understood as living creatures, sacred and an integral part of society. The Witch Tree of Aberuthven may have been just such a site—where the local farmers, peasants, wise women and village people held their traditional gatherings and rites. It is now all but gone…

References:

- Gomme, Laurence, Primitive Folk-Moots, Sampson Lowe: London 1880.

- Hunter, John, Chronicles of Strathearn, David Philips: Crieff 1896.

- Reid, Alexander George, The Annals of Auchterarder and Memorials of Strathearn, Davdi Philips: Crieff 1899.

- Wilson, James, Lowland Scotch as Spoken in the Lower Strathearn District of Scotland, Oxford University Press 1915.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian