Standing Stone / Cup Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NO 27997 43473

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 30824

- Siward’s Stone

- Witches’ Stone

Getting Here

MacBeth’s Stone, near Meigle

From the centre of Meigle village, you need to go along the country lane southwest towards the village of Ardler (do not go on the B954 road). About three-quarter of a mile (1.25km) along—past the entrance to Belmont Castle—you’ll reach a small triangle of grass on your left, and a driveway into the trees. Walk down here, past the first house—behind which is the stone in question. A small path takes you through the trees and round to it. You can’t really miss it!

Archaeology & History

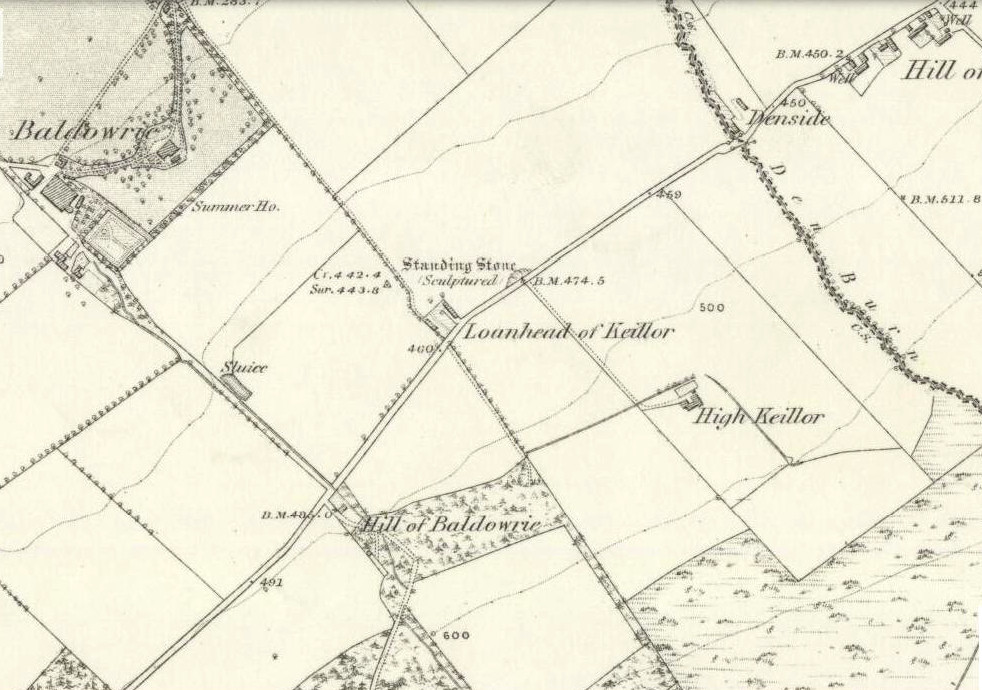

MacBeth Stone on 1st OS-map

This is a magnificent site. A giant of a stone. Almost the effigy of a King, petrified, awaiting one day to awaken and get the people behind him! It has that feel of awe and curiosity that some of us know very well at these less-visited, quieter megalithic places. Its title has been an interchange between the Scottish King MacBeth and the witches who played so much in his folklore, mixed into more realistic local traditions of other heathen medicine-women of olde…

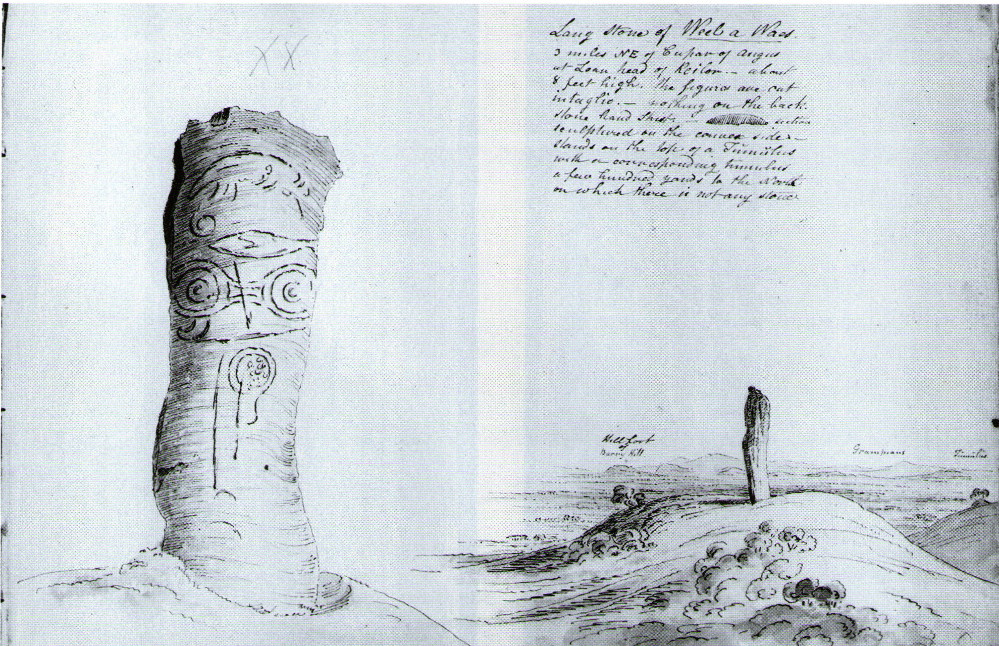

The first account of this giant standing stone came from the travelling pen of Thomas Pennant (1776) who, in his meanderings to the various historical and legendary sites of Meigle district, wrote that

“In a field on the other side of the house is another monument to a hero of that day, to the memory of the brave young Seward, who fell, slain on the spot by MacBeth. A stupendous stone marks the place; twelve feet high above ground, and eighteen feet and a half in girth in the thickest place. The quantity below the surface of the Earth is only two feet eight inches; the weight. on accurate computation amounts to twenty tons; yet I have been assured that no stone of this species is to be found within twenty miles.”

It was visited by the Ordnance Survey lads in 1863, several years after one Thomas Wise (1855) had described the monolith in an article on the nearby hillfort of Dunsinane. But little of any substance was said of the stone, and this is something that hasn’t changed for 150 years, despite the huge size of this erection! Local historians make mention of it in their various travelogues, but the archaeologists haven’t really given the site the attention it deserves. Even the Royal Commission (1994) report was scant; and apart from suggesting it to have a neolithic provenance, they merely wrote:

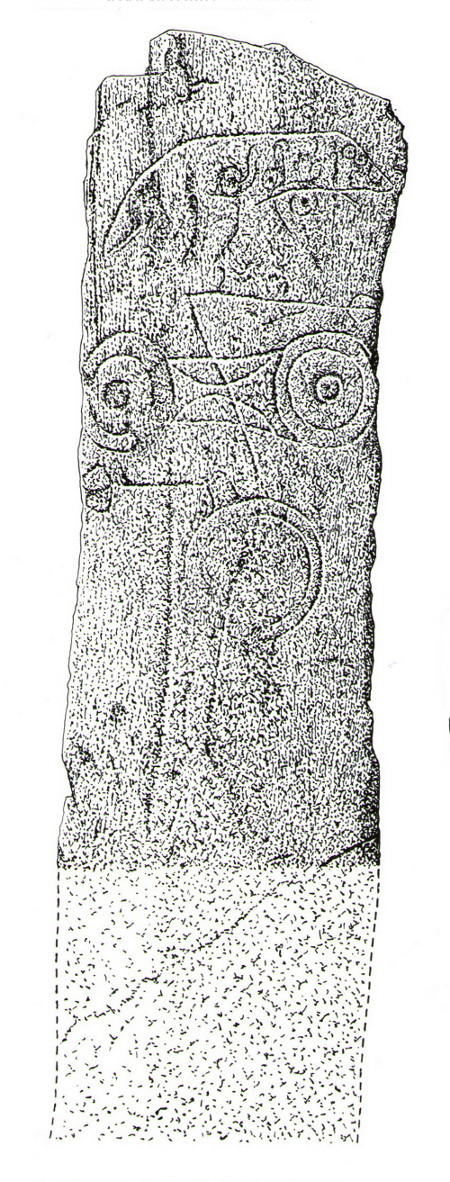

“Rectangular in cross-section, the stone tapers to a point some 3.6m above the ground; each of its sides is decorated with cupmarks, as many as forty occurring on the east face and twenty-four on the west.”

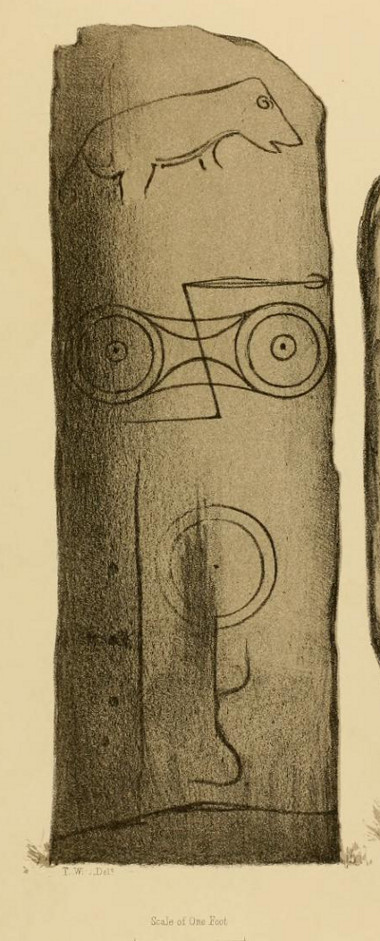

MacBeth Stone (Wise 1884)

East face of MacBeth’s Stone

Thankfully, the fact that there are cup-markings on the stone has at least given it the attention it deserves amongst the petroglyph students. The first account of the cup-markings seem to have come from the pen of Sir James Simpson (1867) who mentions them, albeit in passing, in his seminal work on the subject. A few years later however, the same Thomas Wise visited MacBeth’s Stone again, and not only described the carvings, but gave us our first known illustration in his fascinating History of Paganism (1884). He told it to be,

“A large boulder, some 12 tons in weight, situated within the policies of Belmont Castle, in Strathmore, Perthshire…is supposed to have been erected on the spot where MacBeth was slain. Two feet above the ground this boulder has a belt of cups of different sizes, and in irregular groups. None of these cups are surrounded by incised circles or gutters. This boulder was probably intended for some sacred purpose, as it faces the SE.”

Running almost around the middle of the standing stone, on all four sides, are the great majority of the cup-markings (no rings or additional lines are visible). They were very obviously etched into the stone after it had been erected, not before. This is in stark contrast to the cup-and-rings found on the standing stones at Machrie, Kilmartin and elsewhere, where we know the carvings were done before the stones were stood upright.

Cup-narks on western face

Cups on the western face

On the northern face of the stone is one possible cup-marking, and three of them are etched onto its south face; but the majority of them, forty, are on its western face, and twenty-five on its eastern side. The great majority of them on the east and west sides occur roughly in the middle of the stone, almost like a ‘belt’ running across its body. Those on the eastern face are difficult to discern as a thick layer of lichens covers this side, so there may be even more beneath the vegetation.

An increasingly notable element in the singular monoliths of this region, echoed again here, is that at least one side of the standing stone is smooth and flat—in the case of MacBeth’s Stone the flat face is the eastern one. Whether this was a deliberate feature/ingredient in some of the standing stones, I do not know. If there was such a deliberate reason, it would be good to know what it meant!

The ‘face’ in the top of the stone

Close-up of Macbeth’s face

Another fascinating feature at this site was noticed by Nina Harris of ‘Organic Scotland’. Meandering around the stone in and out of the trees, she called our attention to a fascinating simulacra when looking at the upper section of the monolith on its southern side. At first it didn’t seem clear – but then, as usual, the more you looked, the more obvious it became. A very distinct face, seemingly male, occurs naturally at the top of the stone and it continues as you walk around to its heavily cup-marked western side. It’s quite unmistakable! As such, it has to be posited: was this simulacra noticed by the people who erected this stone and seen as the spirit of the rock? Did it even constitute the reason behind its association with some ancestral figure, whose spirit endured here and was petrified? Such a query is neither unusual nor outlandish, as every culture on Earth relates to such spirit in stones where faces like this stand out.

But whatever your opinion on such matters, when you visit this site spend some time here, quietly. Get into the feel of the place. And above all, see what impression you get from the stony face above the body of the stone. Tis fascinating…..

Folklore

Known locally as being a gathering place of witches, the site is still frequented by old people at certain times of the year, at night. The stone’s association with MacBeth comes, not from the King himself (whose death occurred many miles to the north), but one of his generals. In James Guthrie’s (1875) huge work on the folklore of this region, he told that this giant

“erect block of whinstone, of nearly twenty tons in weight…(is) said to be monumental of one of his chief officers”,

which he thought perhaps gave the tale an “air of probability about it.” But Guthrie didn’t know that this great upright was perhaps four thousand years older than the MacBeth tradition espoused! However, as Nick Aitchison (1999) pointed out in his singular study of the historical MacBeth,

“another MacBeth was sheriff of Scone in the late twelfth century and it is possible that he, and not MacBeth, King of Scots, is commemorated in the name.”

He may be right. Or it the name may simply have been grafted onto the stone replacing a more archaic relationship with some long forgotten heathen elder. We might never know for sure.

When Geoff Holder (2006) wrote about the various MacBeth sites in this area, he remarked that the folklore of the local people was all down to the pen of one Sir John Sinclair, editor of the first Statistical Account of the area—but this is a gross and probably inaccurate generalization. Nowhere in Holder’s work (or in any of his other tomes) does he outline the foundations of local people’s innate subjective animistic relationship to their landscape and its legends; preferring instead, as many uninformed social historians do, to depersonalise the human/landscape relationships, which were part and parcel of everyday life until the coming of the Industrial Revolution. Fundamentally differing cultural, cosmological and psychological attributes spawned many of the old myths of our land, its megaliths and other prehistoric sites. It aint rocket science! Sadly, increasing numbers of folklore students are taking this “easy option” of denouncement, due to educational inabilities. It’s about time researchers started taking such misdirected students to task!

References:

- Aitchison, Nick, MacBeth – Man and Myth, Sutton: Stroud 1999.

- Coutts, Herbert, Ancient Monuments of Tayside, Dundee Museum 1970.

- Guthrie, James C., The Vale of Strathmore – Its Scenes and Legends, William Paterson: Edinburgh 1875.

- Hazlitt, W.C., Faiths and Folklore: A Dictionary, Reeves & Turner: London 1905.

- Holder, Geoff, The Guide to Mysterious Perthshire, History Press 2006.

- MacNeill, F. Marian, The Silver Bough – volume 1, William MacLellan: Glasgow 1957.

- MacPherson, J.G., Strathmore: Past and Present, S. Cowan: Perth 1885.

- Michell, John, Simulacra, Thames & Hudson: London 1979.

- Pennant, Thomas, A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the Hebrides – volume 2, London 1776.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, South-East Perth: An Archaeological Landscape, HMSO: Edinburgh 1994.

- Simpson, James, Archaic Sculpturings of Cups, Circles, etc., Upon Stones and Rocks in Scotland, England and other Countries, Edmonston & Douglas: Edinburgh 1867.

- Wise, Thomas A., “Notice of Recent Excavations in the Hill Fort of Dunsinane, Perthshire,” in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 2, 1855.

- Wise, Thomas A., History of Paganism in Caledonia, Trubner: London 1884.

Acknowledgements: With huge thanks to Paul Hornby for his help getting me to this impressive monolith; and to Nina Harris, for prompting some intriguing ideas.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian