Sacred Hill: OS Grid Reference – SE 8731 9377

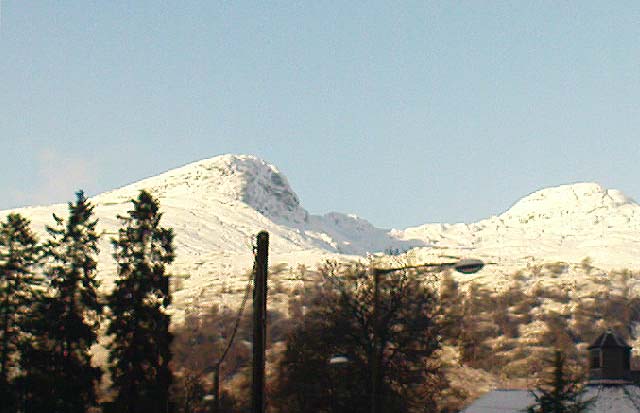

From Pickering, take the A169 towards Whitby. When you get to the Car Park at the ‘Hole-of-Horcum’ – (you can’t miss it), park the car and walk North along the side of the road towards Whitby. After 60 yds, take the track East. Follow this for approximately a mile until the track splits. Take the concrete track left towards the farmhouse of ‘Newgate Foot’. Go through the yard past the house on the right, and you will come to a stream and a gate and there, ahead of you, rises Blakey Topping…

Archaeology & History

The giant hill of Blakey Topping was recorded as early as 1233 CE and in a simplistic style just means the ‘black mound’; but this derivation has additional ingredients, implying it as a ‘black meeting-place’ or moot. Black in the etymological sense also implies ‘shining’ and it may also relate to the northern airt of black (meaning death, darkness, north, etc), when you’re stood at the ruined stone circle 400 yards to the south. But I’m speculating here…

Several 19th century antiquarians suggested there may have once been a cairn on top of the hill, but others who’ve explored this idea seem to have put it to bed.

Folklore

This great hill is well recognised amongst local people and, to this day, its animistic creation myths and other folklore elements are still spoken. When the photographer James Elkington recently visited the nearby standing stones, he bumped into the old farmer who told him how his father had seen the faerie-folk on the hill many years back. And its modern reputation as a gorgeous site adds to such lore, which dates way back.

In Frank & Harriett Elgee’s (1933) archaeology work, they narrated the old creation myth that local people used to tell of this great hill,

“A witch story related by a native 25 years ago attempts to explain two conspicuous natural features two miles apart on Pickering Moor; Blakey Topping, an isolated hill, and the Hole of Horcum, a deep basin-shaped valley. The local witch had sold her soul to the devil on the usual terms, but when he claimed it, she refused to give it up, and flew over the moors, with the devil in hot pursuit. Overtake her he could not, so he grabbed up a handful of earth and flung it at her. he missed his aim and she escaped. The Hole of Horcum remains to prove where he tore up the earth and Blakey Topping where it fell to the ground.

“From our point of view the significance of this story lies in the fact that between the Hole and the Topping there is a Bronze Age settlement site at Blakey Farm, with its stone circle. The rough trackway leading from the Hole to the circle is known as the Old Wife’s Way, presumably also marking the witch’s flight. This, together with other Old Wife’s Ways, preserves as it were Bronze Age church tracks”.

A relative variation on this tells that the Hole of Horcum was made by the local giant, Wade. He was having a row with his wife, Bell, and got so angry that he scooped out a lump of earth and threw it at her. The huge geological feature known as the Hole of Horcum is the dip left where he scooped out the earth, and Blakey topping, the clod itself, resting in situ where it landed. A christian appropriation of the story replaces Wade and his wife with their ‘devil’: a puerile element unworthy of serious consideration.

In more recent times, the old geomancer Guy Ragland Phillips (1976; 1985) found that a number of alignments, or leys (known as a ‘node’), centred on Blakey Topping: twelve in all, reaching out and crossing numerous holy wells, prehistoric tumuli, standing stones, etc. The precision of the alignments is questionable, yet the matter of the hill being a centre-point, or omphalos, would seem moreso than not.

References:

- Elgee, F. & H.W., The Archaeology of Yorkshire, Methuen: London 1933.

- Phillips, Guy Ragland, Brigantia, RKP: London 1976.

- Phillips, Guy Ragland, The Unpolluted God, Northern Lights: Pocklington 1987.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the North Riding of Yorkshire, Cambridge University Press 1928.

Links:

Acknowledgements: Big thanks to the photographer, James Elkington, for use of his photos in this profile. Cheers mate.

© Paul Bennett & James Elkington, The Northern Antiquarian