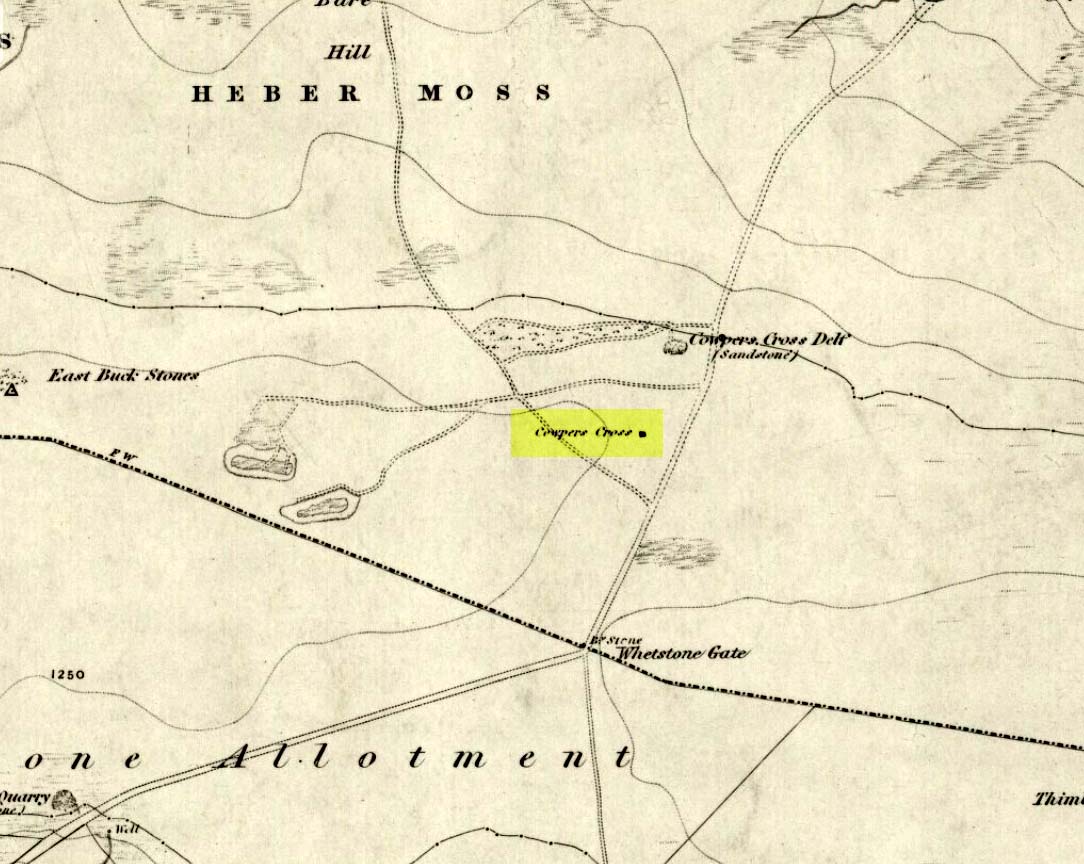

Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – SD 98665 41698

The easiest way to get here is via Cowling – though you can approach the place via moorland roads from Sutton-in-Craven, Oakworth and Keighley, but Cowling’s the closest place (so we’ll take it from there). Turn east off the A6068 up Old Lane at the Ickornshaw side of town and go up the steep and winding road until you hit the moors. Just as the road levels out with walling on either side of the road, there’s some rough ground to your left. You can park here. You’ll blatantly see our Hitching Stone on the moorland a few hundred yards above you on the other side of the road. Walk up the usually boggy footpath straight to it!

Archaeology & History

For me, this is a superb place! Each time I come here the place becomes even more and more attractive — it’s like it’s calling me with greater strength with each visit. But that aside…

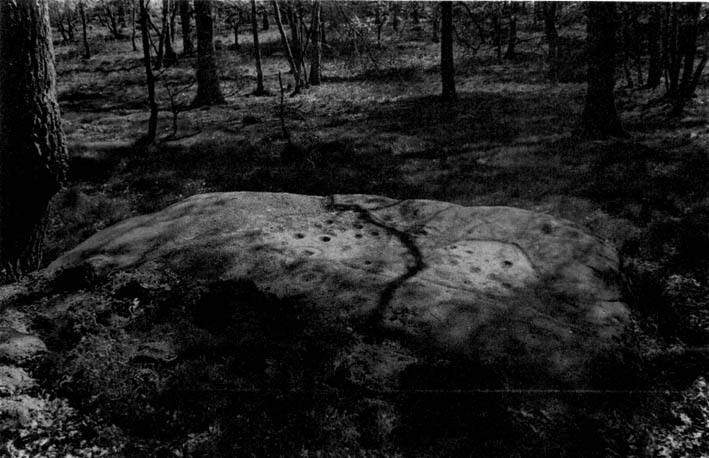

Supposedly the largest single boulder in Yorkshire, it possesses several legends, aligns with the sacred Pendle Hill in Lancashire, is an omphalos (centre of the universe spot) and has other good points too! My first visit here was near the end of the Great Drought of 1995. All of the streams and springs had dried up on the moors but, on the very top of this huge rock, measuring at least 8 feet by 4 feet across (and 3 feet deep) was a large pool of water, not unlike a bath, in which a couple of you could easily bathe (and do more besides, if the fancy takes you!). It was surreal! Water-boatmen and other insects were living in this curious pool on top of the rock. Yet all other water supplies for miles around had long since dried-up. It didn’t really seem to make sense.

On the west-facing side of the boulder, about 8 feet up, is a curious deep recess known as the Druid’s or Priest’s Chair, into which initiates were sat (facing Pendle Hill, down which it seems the equinox sun “rolls”) and is believed, said Harry Speight, “to have some connection with Druidical worship, to which tradition assigns a place on these moors.” If you climb up and inside the Priest’s Chair section you’ll notice a curious “tunnel” that runs down through the boulder, about 12 feet long, emerging near the northern base of the rock and out onto the moor itself. This curious tunnel through the rock is due to the softer rock of a fossilised tree (Lepidodendron) crumbling away — and not, as Will Keighley (1858) believed, “the mould or matrix of a great fish.” When we visited the stone the other day in the snow, we noticed how the inner surface of this tunnel was shimmering throughout its length as if coated in a beautiful crystalline lattice (you can sort-of make this out in the image here, where the numerous bright spots on the photo are where the rock was lit up). Twas gorgeous!

The boulder lies at the meeting of five boundaries, and was the starting point for horse-racing event until the end of the 19th century. A short distance away “are two smaller stones, the one on the east called ‘Kidstone’, the other ‘Navaxstone’, which stands at the terminus of the race-course.” (Keighley 1858) Lammas fairs were also held here, though were stopped in 1870.

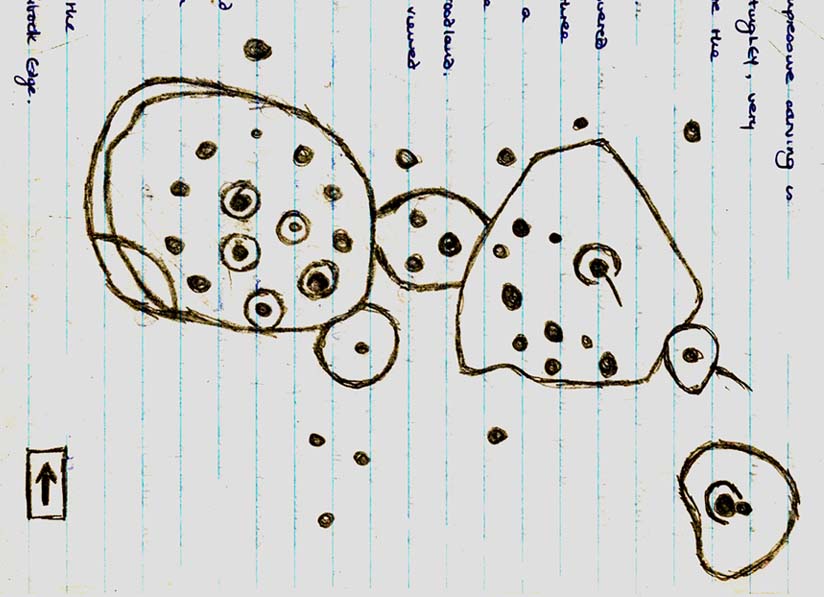

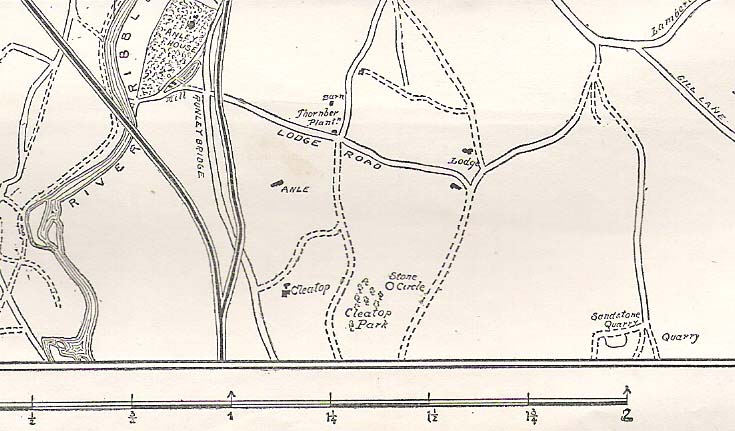

The cup-marked Winter Hill Stone a few hundred yards to the northeast, which I previously thought aligned with this site around winter solstice, but which happens to be a few degrees of arc off-line, would have indicated a very early mythic relationship, but this thought may now have to be put to bed. I’ve not checked whether the winter solstice alignment shown in the photo below (with the Hitching Stone being shown on the near-horizon as the sun rose on winter solstice, 2010, from Winter Hill Stone) would have been closer in neolithic times or not. Summat to check out sometime in the future maybe…

This aside, there is little doubt that this was an important sacred site to our ancestors.

Folklore

Legend has it that the Hitching Stone used to sit on Ilkley Moor. But it was outside the rocky house of a great witch who, fed up by the constant intrusion the boulder made to her life, tried all sorts of ways to move it, but without success. So one day, using magick, she stuck her wand (or broomstick) into the very rock itself and threw it several miles from one side of the valley to the other until it landed where it still sits, on Keighley Moor.

A variation on the same tale tells that she pushed it up the hill from the Aire valley bottom. The “hole” running through the stone is supposed to be where our old witch shoved her broomstick!

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Gray, Johnnie, Through Airedale form Goole to Malham, G.F. Sewell: Bradford 1891.

- Keighley, William, Keighley, Past and Present, R. Aked: Keighley 1858.

- Wood, Eric, Cowling: A Moorland Parish, Cowling Local History Society 1980.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian