Chambered Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SV 877 131

Archaeology & History

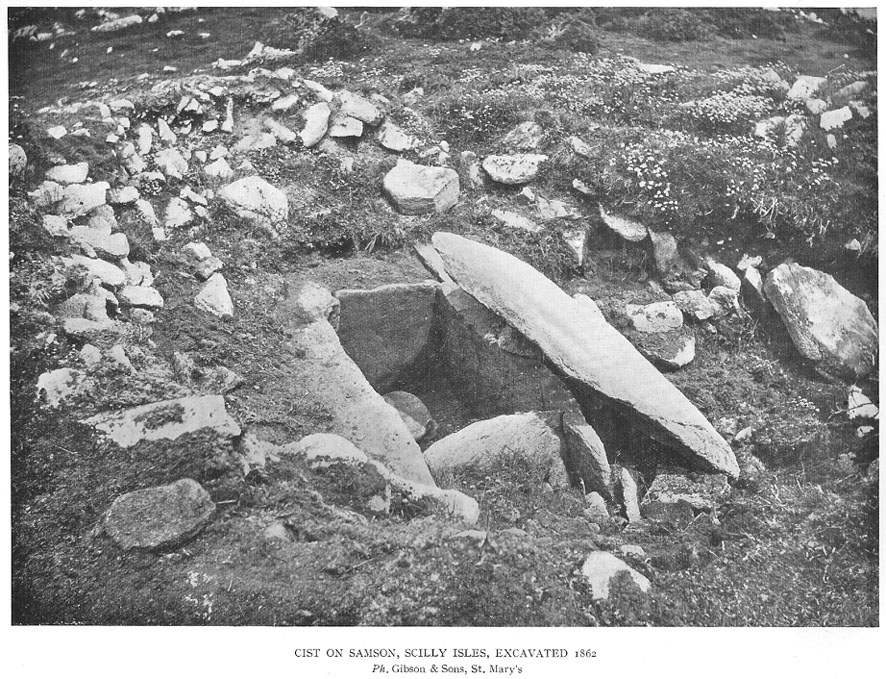

On the north side of Samson island there are several chambered tombs and cairns scattered around the edges of aptly-named North Hill; but the one illustrated here was one of the first to be excavated in 1862-3. Although O.G.S. Crawford (1928) wrote about the site in his essay on Cornish cists — from where this old black-and-white photo of the site has been taken — it was described in much greater detail in Borlase’s (1872) archaeological magnum opus of the day. In his time, this now much-denuded burial site had all the outer hallmarks of being a large tumulus. This was described in some detail in a paper written by one Mr Augustus Smith (read at a Meeting of the Royal Institution of Cornwall in May, 1863) who was fortunate enough to be one of the first people to unearth this great tomb and find the site untouched since it had been laid, thousands of years earlier. Citing extensively from Smith’s notes, Borlase told:

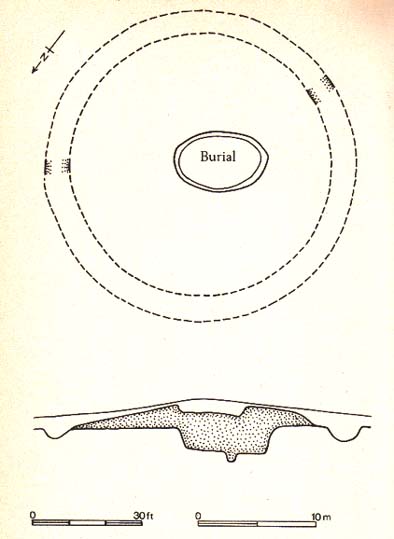

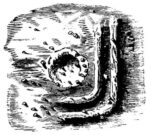

“The Barrow…is situated with four or five others, mostly rifled on the…high ground at the northern end. “The mound, in its outer circumference, measured about 58 feet, giving, therefore, a distance of near upon 30 feet to its centre, from where the excavation was commenced. For about 18 or 20 feet the mound appeared entirely composed of fine earth, when an inner covering, first of smaller and then or large rugged stones, was revealed. These were carefully uncovered before being disturbed, and were then one by one displaced till a large upright stone was reached, covered by another of still more ponderous dimensions, which projected partially over the edges of the other. At length this top covering, of irregular shape, but measuring about 5 feet 6 inches in its largest diameter, was thoroughly cleared of the superincumbent stones and earth, and showed itself evidently to be the lid to some mysterious vault or chamber beneath.” On the lid being removed, there was “disclosed to view an oblong stone chest or sarcophagus beneath” on the floor of which, “in a small patch,” “a little heap of bones, the fragmentary framework of some denizen of earth, perhaps a former proprietor of the Islands—were discovered piled together in one corner.

“”The bones were carefully taken out, and the more prominent fragments, on subsequent examination by a medical gentleman, were found to give the following particulars: – Part of an upper jawbone presented the alveolæ of all the incisors, the canines, two cuspids and three molars, and the roots of two teeth, very white, still remaining in the sockets. Another fragment gave part of the lower jaw with similar remains of teeth in the sockets. All the bones had been under the action of fire and must have been carefully collected together after the burning of the body. They are considered to have belonged to a man about 50 years of age…

“”The bottom of the sarcophagus was neatly fitted with a pavement of three flat but irregular-shaped stones, the joints fitted with clay mortar, as were also the insterstices where the stones forming the upright sides joined together, as also the lid, which was very neatly and closely fitted down with this same plaster.

“”Two long slabs, from seven to nine feet in length, and two feet in depth, form the sides, while the short stones fitted in between them make the ends, being about 3½ feet apart, and to fix which firmly in their places, grooves had been roughly worked in the larger stones.” The paving stones had been “embedded immediately upon the natural surface of the granite of which the hill consists.”

References:

- Borlase, William Copeland, Nænia Cornubiæ, Longmans Green: London 1872.

- Crawford, O.G.S., “Stone Cists,” in Antiquity Journal, volume 2, no.8, December 1928.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian