Legendary Rock (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 5493 7710

Also known as:

- Historic Environment Record Stirling 3745

Echo Stone on 1865 Map

Archaeology & History

A recent communication to us from Alan McBride (2021), the historian for the Mugdock Country Park, has given us an accurate appraisal of this site which has, sadly, passed into the Realm of the Lost. The following paragraphs are what Mr McBride has discovered in his personal exploration looking at the history of this once legendary stone. He writes:

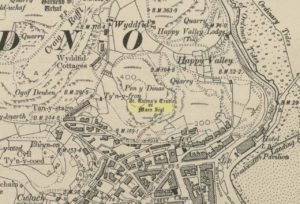

“As the name suggests, one would stand at, or on, the Echo Stone facing Mugdock Castle and upon shouting the voice would reverberate off the high walls of the castle and come back as a long clear echo. It was a feature on Montrose’s estate, but when it came into existence is unknown. Historical maps give an idea of when it disappeared though. The Ordnance Survey map of 1860 shows the Echo Stone adjacent to Mugdock Castle in open ground (now woodland) close to the boundary of Mugdock Wood at the steep crag. The Ordnance Survey map revision of 1896 shows the Echo Stone and in brackets (site of) and the area planted as woodland.

“Put into historical context, the map of 1860 was produced not long after Archibald McLellan’s tenancy at Mugdock Castle, at which point the old Georgian house was still standing. By the time the revised map of 1896 was produced, John Guthrie-Smith was the tenant of Mugdock Castle. He was responsible for demolishing the old Georgian house and building the Victorian mansion in its place. He was also responsible for the design and planting of many trees in the areas surrounding Mugdock Castle and Loch, one of these areas being where the Echo Stone was located. It is believed by local historians that the stone, decorated with engravings, was either stolen during the time the castle and estate was vacant after McLellan’s death, that it was pushed over the crag into Mugdock Wood where it remains buried under vegetation, or that it was removed during the planting of the area by Guthrie-Smith.”

Of particular interest to myself (PB) is the mention of it being “decorated with engravings.” My first response (obviously!) was that such carvings may be prehistoric. A short distance east of here—and also lost—was the Loch Ardinning cup-and-ring stone, so our Echo Stone may have been a carved compatriot. When I enquired about this, Mr McBride told me,

“Regarding the stone being decorated with engravings, this was a local historian who told me this many years ago. He had been told himself, when he was younger, that the Echo Stone would have been a feature seen from the castle and therefore had decorative features on it. He has since passed away and it is the only reference I’ve had to it being decorative. It would make sense though.”

An early literary record of the stone can be found in Hugh MacDonald’s (1854) work, in which he wrote:

“There is an echo of considerable local celebrity at Mugdock, the reverberative powers of which are frequently put to the test by visitors. The spot from which the echo is most distinctly heard is a slightly projecting rock, on a verdant declivity, about a hundred yards to the south of the castle. A person standing on this, looking towards the edifice, and speaking pretty loudly, will hear his words, or even short sentences uttered by him, repeated with startling distinctness, as if from some mimic at the old tower. Of course, we give the echo sundry specimens of our vocality, and to its credit we must say that it flings them back with amazing fidelity. Paddy Blake’s echo, which on the question being put to it of ‘How are you?’ invariably answered ‘Pretty well, I thank you!’ was unmistakeably a native of the land of Bulls. The Mugdock one must be as decidedly Scottish, as it answers each question put to it by asking another. If there were any doubt on this subject, however, we might mention, in support of our supposition, that it is quite au fait at the Gaelic, as we proved to the entire satisfaction of a cannie bystander, who, after listening in silence for some time to our mutual interrogations in that classic tongue, at length exclaimed, ‘Od, man, that’s curious! Wha wad hae thocht that a Lawlan’ echo could hae jabbered Gaelic?'”

Samuel Lewis, writing before 1846, told us that,

“At a distance of about 300 yards from this castle is a remarkable echo, which distinctly reverberates a sentence of six monosyllables, if uttered in a loud tone; and this not till a few seconds after the sentence is completed”.

We can only speculate as to how people in distant times reacted to this echo, and it is interesting how MacDonald’s Gaelic-speaking friend reacted, almost as if he believed it to be a living organism which he did not expect to reply in his own language.

References:

- McBride, Alan, Personal Communication, April 15, 2021

- MacDonald, Hugh, Rambles Round Glasgow, Descriptive, Historical & Traditional, John Smith & Son: Glasgow 1854 & 1910.

- Lewis, Samuel, A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland – 2 volumes, S Lewis & Co.: London 1846

Links:

- Mugdock Country Park

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Alan McBride for the revisions and corrections regarding this site profile.

© Paul Bennett, Paul T. Hornby & Alan McBride, The Northern Antiquarian 2016