Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 77451 20648

From Comrie take the B827 road (towards Braco) out of town and where the fields open up on both sides of you, 400 yards along the straight road you’ll see a large bulky stone right by the roadside (it’s the standing stone known as the Roman Stone). Stop here and look on the ground just a couple of yards past the monolith where, amidst the grasses and mosses, you’ll see this small smooth stone (you might have to roll some of the mosses back to see it properly).

Archaeology & History

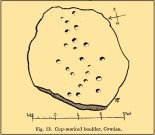

More than a hundred years ago when John MacPherson (1896) wrote his essay on the history of this area, he described there being “three large stones, supposed to be the remains of a Druidical temple.” He was talking about the Roman Stone here, with its two companions—although only the Roman Stone remains upright today. He noted that one of them, on the ground was “a round, flat boulder” which “bears upon its surface cup-marks arranged in irregular concentric circles.”

This seems to have been the first mention of the carving. Fifteen years later when the great Fred Coles (1911) looked at the same standing stones, he found the adjacent petroglyph to still be in situ, stating that,

“The surface is covered with a group of twenty-two neatly made cups … the majority being about 2 inches in diameter, with a few much smaller. Two cups measure only 1 inch in diameter.”

A few years after this, members of the Perthshire Natural History Society on an excursion to Glen Artney in May 1914, stopped here to have a look at the same standing stones and they also pointed out that one of the stones “lying on the ground…is remarkable for the numerous cup-marks on its surface.” In truth, it’s not that remarkable compared to some of the other carvings, but it’s still worth checking out when visiting the other sites in the area. Many of the cups that were visible a hundred years back are difficult to make out unless the light is good; and it seems as if some of them have been chipped away, perhaps due to farming activity.

References:

- Barclay, W., “Winter Session, 1914-1915,” in Transactions & Proceedings Perthshire Society Natural Science, volume 6, 1919.

- Coles, Fred, “Report on Stone Circles in Perthshire, Principally Strathearn,” in Proceedings Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 45, 1911.

- Hunter, John, Chronicles of Strathearn, David Philips: Crieff 1896.

- Mac Pherson, John, “At the Head of Strathearn,” in Hunter’s Chronicles of Strathearn (David Philips: Crieff 1896).

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian