Tumulus (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – TM 0628 2022

Archaeology & History

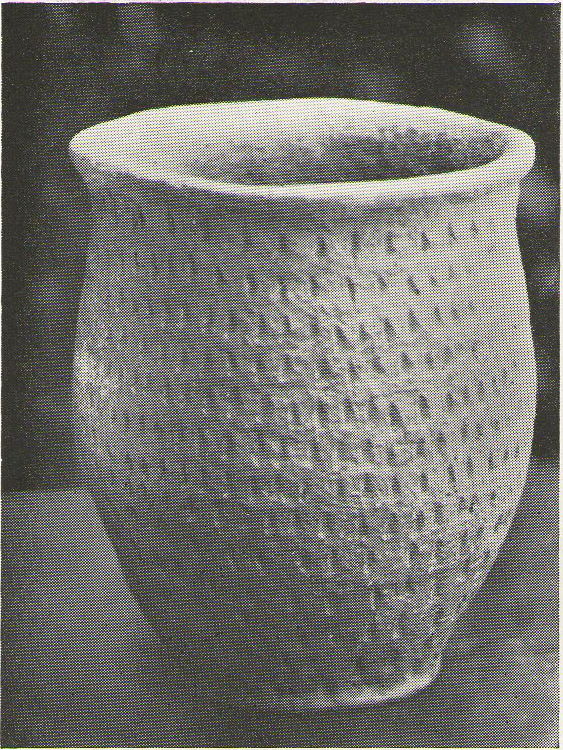

In a region well known for the finding of early British remains (Belloc 1905), another prehistoric burial mound was destroyed in the Essex landscape simply due to ignorance and neglect. Thankfully once more we have local antiquarians and an astute schoolgirl for discovering and preserving a record of this site, otherwise we’d have no record of the place at all! Described in M.R. Hull’s (1946) article on some of the Bronze Age relics of the area, he told how a well-preserved urn in the edge of the tumulus,

“was found in June 1942 by a schoolgirl, Miss Anne Pilkington, on the top of the hill overlooking Alresford Creek and the Colne Estuary, about 70 yards northwest of Bench Mark 74.8 and 560 yards slightly west of south from Alresford church, west of the road to the creek and south of the lane running west along the north side of the field. This is the northern limit of a huge gravel-pit. She noticed the vessel standing upright in the side of the pit and recovered it. Nothing else was noticed…

“Afterwards the diary of our late Fellow, Mr P.G. Laver came into my hands and I find under the date 8th July, 1922, that he noticed, when motoring past the site, ‘a definite tumulus, but much ploughed down, now barely 18ins above the field level. It is close to the road through the field, the centre being roughly 20 yards S of the road and about 200 yards from the road to the ford.’ The sketch-plan leaves no doubt on the identity of the site.”

Annoyingly though, Mr Hull didn’t think it worthwhile to reproduce this alleged sketch-map. He did however give us a good description of the urn and its position in the ground, saying,

“The vessel is stated to have been about 5ft below the surface when found, but I am not certain whether the top-soil had been removed or not. The clay is fine, burnt light red, but black within, and the whole body is covered with horizontal lines impressed in exactly the same way as (those on the Flag Inn urn), but much less clearly. The base is slightly hollowed beneath and is not far from having a foot-ring.”

Folklore

Mr Hull (1946) also made an interesting comment on the views of local people about the site where Anne had found this urn, reminding me of what Highland and hill folk would have put down to faerie-lore, though no such memory was noted. He told:

“On enquiry I learnt that no one had observed a mound at the spot, but that it had been observed that exactly there the corn, when the field was cultivated, grew taller and greener in a large round patch”!

References:

- Belloc, Hilaire, The Old Road, Archibald Constable: London 1905.

- Hull, M.R., “Five Bronze Age Beakers from North-East Essex,” in Antiquaries Journal, volume 26, Jan-April 1946.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian