Enclosures: OS Grid Reference – SE 1338 5493

ON the A59 Harrogate to Skipton road, right on top where it crosses the barren moors, get to the parking spot right near where the road levels out at the highest point (2-300 yards past the turning to the derelict Dovestones Quarry). From here, go thru the gate onto the moor for about 100 yard. Then turn straight east (left) for another few hundred yards till y’ reach the spot marked as Gill Head Peat Moor on the OS-map. This small standing stone (right) is where you need to start – the other remains continue east of here.

Archaeology & History

The discovery of this site began in April 2005, when rock art student Richard Stroud and I were exploring the moors here and he called our attention to what seemed like a singular upright standing stone, some 3 feet high, with a debatable cup-marking on top, standing amidst a scatter of smaller stones running north and south from here, implying that the stone may have been a part of some much denuded walling from our ancient past. But we weren’t sure—and simply noted its location (at SE 13378 54924) and carried on our way. But in revisiting this site after looking at some old archaeology papers, Paul Hornby and I chanced to find a lot more on the burnt heathland running east of here.

The upright stone found by Mr Stroud is certainly part of some ancient walling, but it is much denuded and falls back into the peat after only a short distance. A short distance west of this stone is a small cairn which seems of more recent origin; but due east, along the flat plain on the moorland itself, the burnt heathland showed a scattering of extensive human remains, comprising mainly of walling, hut circles and possible cairns—lots of it!

One issue we have to contend with on this moorland is the evidence of considerable peat-cutting in places, which was being done on a large scale into the Victorian period. Scatterings of medieval work are also found across this moor, in places directly interfering with little-known Bronze Age monuments in the middle of the remote uplands. There is no doubt that some of these medieval and later workings have destroyed some of the uncatalogued prehistoric archaeological remains on this moor. But thankfully, on the ridge running west to east along Gill Head to above the source of the Black Dike, scattered remains of human habitation and activity are still in evidence. The only problem with what we’ve found, is the date…

In 1960, Mr J. Davies first mentioned finding good evidence of flint-workings at a site close by; then described his discoveries in greater detail in the Yorkshire Archaeological Journal (1963) a few years later — but contended that the remains were of mesolithic origin. A few years earlier, Mr D. Walker described a similar mesolithic “microlith site” a bit further north at Stump Cross. Earlier still, Eric Cowling (1946) and others had made similar finds on these and adjacent moors. Yet all of them missed this scatter of habitation sites, perched near the edge of the ridge running east-west atop of the ridge above the A59 road. It’s quite extensive and, from the state of the walled remains, seems very early, probably neolithic in origin.

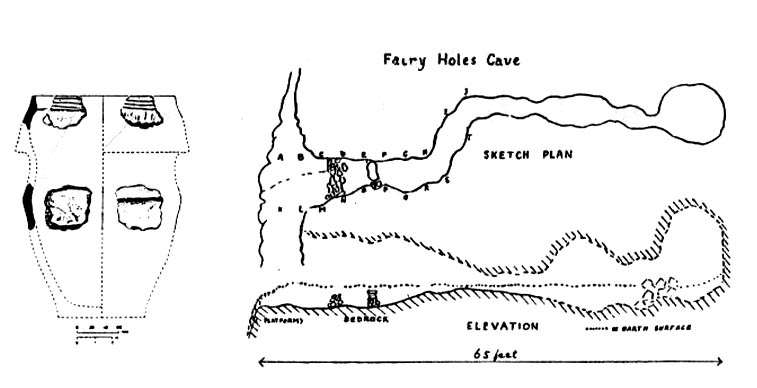

A number of small hut circles, 2-3 yards across, are scattered amidst the heather, with lines of walling—some straight, some not—broken here and there by people who came to gather their peat for fuel. The walling and hut circle remains are very low to the ground, having themselves been robbed for stone it would seem. The area initially appeared to be little more than a mass of stones scattered across the Earth (and much of it is), but amidst this are very clear lines of walls and circles, although they proved difficult to photograph because of the excessive growth of Calluna vulgaris.

A couple of hundred yards south there are remains of one of the many dried black peat-bogs—with one large section that has been tampered with by humans at some point in the ancient past. Over one section of it there has been built a small stone path, or possible fish-trap; plus elsewhere is a most curious rectangular walled structure (right) obviously made by people a long time ago. Also amidst this dried peat-bog are the truly ancient remains of prehistoric tree-roots emerging from the Earth, a few thousand years old at least – and perhaps the last remnants of the ancient forests that once covered these moors.

How far back in time do all these walled remains take us? Iron Age? Bronze Age? Or much much further…? Excavations anyone!?

References:

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Davies, J., “A Mesolithic Workshop in Upper Wharfedale,” in Bradford’s Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 5:1, 1960.

- Davies, J., “A Mesolithic Site on Blubberhouses Moor, Wharfedale,” in Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, part 161 (volume 41), 1963.

- Walker, D., “A Site at Stump Cross, near Grassington, Yorkshire, and the Age of the Pennine Microlith Industry,” in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, volume 22, 1956.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian