‘Standing Stone’: OS Grid Reference – SE 00426 63176

Pretty easy really. Get to the ancient St. Michael’s Church on the dead-end road just outside of Linton village. As you approach it, look into the field on your right. Y’ can’t miss it!

Archaeology & History

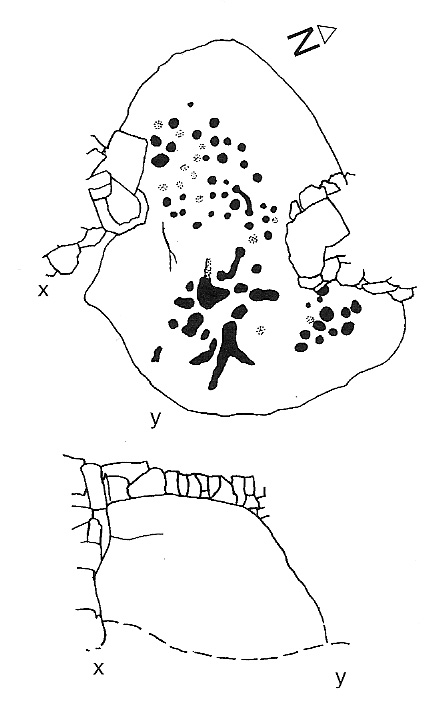

This is an oddity. It could perhaps be little more than one of the Norber erratics found a few miles further north — but it looks more like a smaller version of one of the Avebury sarsens! Just under six-feet tall, it was shown to me by Adrian Lord yesterday (when the heavens subsequently opened and an outstanding downpour-and-half followed), who’d come across it only a week or two earlier themselves when they visited the ancient church next door. The stone certainly aint in any archaeology registers (no surprise there); and as one local man we spoke to yesterday told us, “there used to be several other standing stones in the same field, cos I remember ’em when I was a kid. ” The gent we spoke to seemed to know just about everything about the local archaeology and history of the area (one of those “damn good locals” you’re sometimes lucky to find!). He told us that the other stones which used to be there had been moved by the local farmer over the years, for use in his walls. So it seems that this is the last one standing. What looks like several other fallen stones can be seen further down the field, just next to the church. But this one’s pretty impressive.

The church of St. Michael next door was, tells the information inside, built upon some old pagan site — which gives added thought to this upright stone perhaps being the ruin of an old circle, or summat along those lines. The church, incidentally, is built right next to the River Wharfe.

Not far from here we find an almost inexhaustible supply of prehistoric remains at Grassington and district (less than a mile north). A huge excess of Bronze- and Iron Age remains scatter the fields all round the town. And aswell as the Yarnbury henge close by, there is — our local man told us, “another one which no-one knows abaat, not far away”!

Folklore

The folklore of this area is prodigious! There is faerie-lore, underworld tales, healing wells, black-dogs, ghosts, earthlights – tons of the damn stuff. But with such a mass of prehistoric remains, that aint too surprising. And although there appears no direct reference to this particular stone (cos I can’t find a damn reference about it), the old Yorkshire history magus, Harry Speight (1900), wrote of something a short distance away along the lane from the church. He told that,

“In the field-wall beside the road may be seen some huge glacial boulders, and there is one very large one standing alone in the adjoining field, which from one point of view bears a striking resemblance to a human visage; and a notion prevails among the young folk of the neighbourhood that this stone will fall on its face when it hears the cock crow.”

Just the sort of lore we find attached to some other standing stones in certain parts of the country. And in fact, from some angles, this ‘ere stone has the simulacrum of a face upon it; so this could be the one Speight mentions (though his directions would be, unusually, a little out).

There are heathen oddities about the church aswell: distinctly pre-christian ones. An old “posset-pot” was used for local families to drink from after the celebration of a birth, wedding or funeral here. And at Hallowtide – the old heathen New Year’s Day,

“certain herbs possessed the power of enabling those who were inclined to see their future husbands or wives, or even recognizing who was to die in the near future.”

And in an invocation of the great heathen god (the Church called it the devil), Speight also went on to tell that:

“The practice at Linton was to walk seven times round the church when the doomed one would appear.”

In a watered down version of this, local people found guilty of minor transgressions in and around Linton (thieves, fighters, piss-heads, etc),

“was compelled to seek expiation by walking three time around Linton Church.”

This would allegedly cure them of their ‘sins’! Rush-bearing ceremonies were also enacted here. On the hill above, the faerie-folk lived. And until recently, time itself was still being measured by the three stages of the day: sunrise, midday and sunset; avoiding the modern contrivances of the clock, and maintaining the old pre-christian tradition of time-keeping. Much more remains hidden…

This would allegedly cure them of their ‘sins’! Rush-bearing ceremonies were also enacted here. On the hill above, the faerie-folk lived. And until recently, time itself was still being measured by the three stages of the day: sunrise, midday and sunset; avoiding the modern contrivances of the clock, and maintaining the old pre-christian tradition of time-keeping. Much more remains hidden…

References:

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian