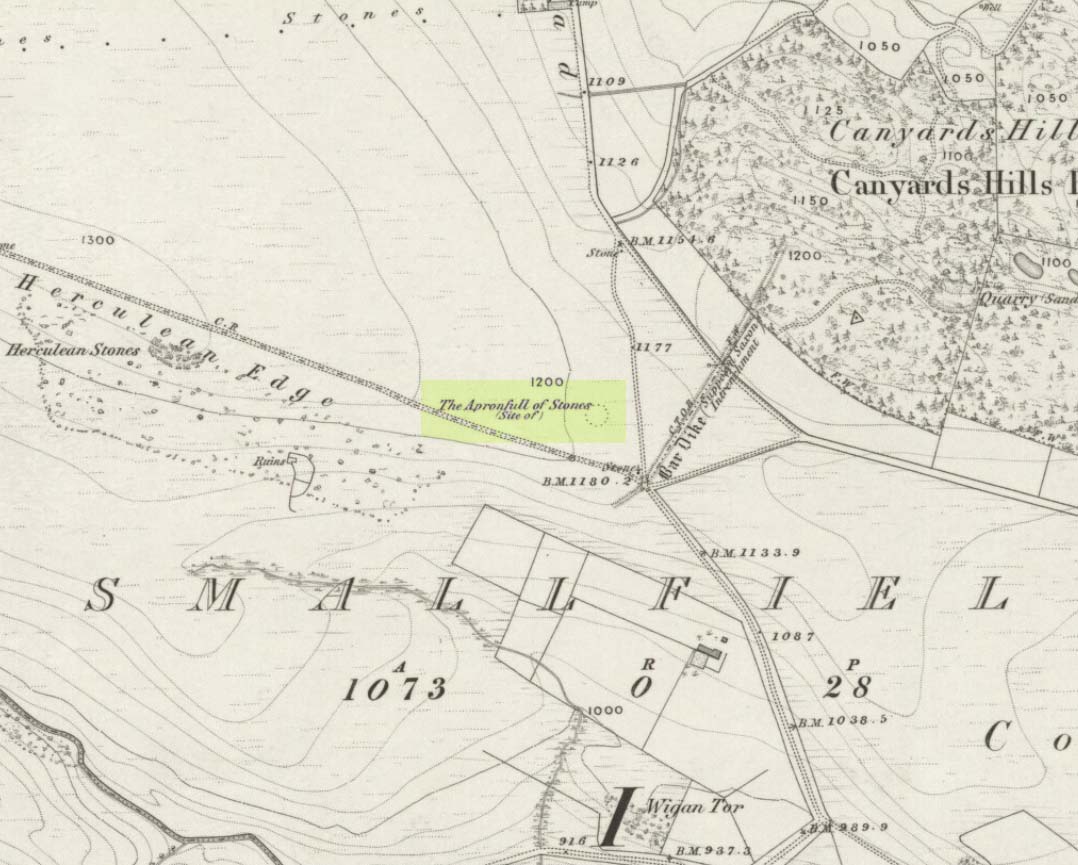

Long Barrow: OS Grid Reference – SE 962 662

Archaeology & History

In the superb work of the legendary J.R. Mortimer (1905) he tells what was found when him and his team excavated this “remarkable barrow,” as he called it. Although Mortimer’s contemporary researcher, Canon Greenwell (1877), also looked at the site, the “mound was covered with a clump of old fir trees” which prevented further examination at the time. Mortimer and his team seemed to have worked here when the trees had been felled and following “a three-week free use of the pick and shovel during July and August, 1878,” they opened up this prehistoric mound to see what lay within.

Their discoveries here were intriguing: for this wasn’t merely a burial site in its early phase but, moreso, a house of the dead no less, where the people whose bodies, or those who cremated ashes were deposited herein, lived in their spirit-life. It was an abode for the spirits of the dead. Mortimer’s lengthy notes tell the story:

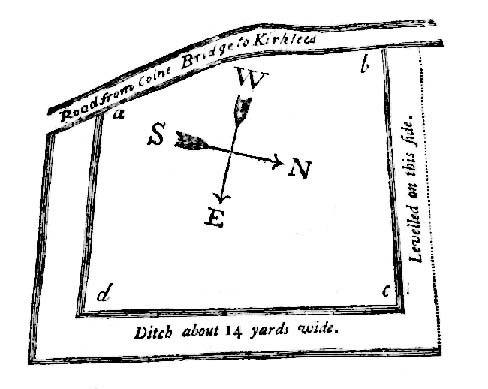

“At the time of opening, it measured 4½ feet from base to summit, and the natural surface of the ground beneath it stood fully 1 foot higher than the present surface of the land for some distance round its margin. It was formed entirely of chalk rubble and soil, mainly obtained from an encircling trench, which on the northwest side was very deep and wide.

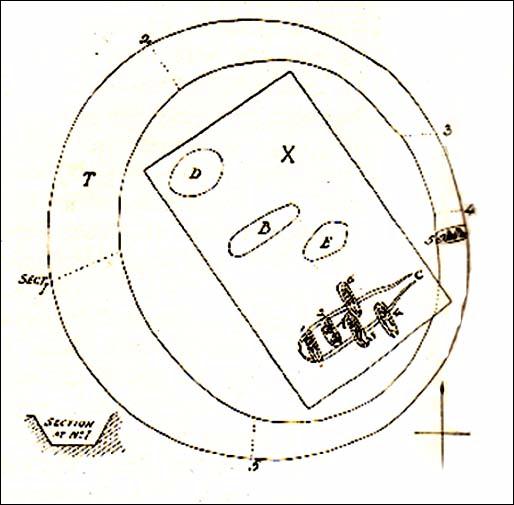

“We turned over the whole of this mound except its outskirts. Near the northwest margin there was an excavation (D on the plan) extending 8 to 10 inches below the base of the mound, and measuring 8½ feet by 6½ feet, the floor of which was covered with a film of dark matter, in which were small bits of burnt wood. No relic, nor the slightest trace of an interment was observed. A little west of the centre (at B) there was s still larger excavation, 18 inches deep. It contained rough chalk, but no traces of an interment. East of this was a third excavation (E), oval in form and 3 feet deep. Like the previous one it was filled with chalk and contained no relic or trace of a skeleton. The digging of these had preceded the erection of the mound, as there were no indications of it having been cut through. These excavations were doubtless graves, the bodies having entirely decayed.

“This was not, however, the case with the secondary and comparatively recent interments of six adult skeletons, found at the south-east side of the mound, 1 foot to 2 feet below its base. Though unaccompanied by any relic, the very narrow form of the graves and the extended and slightly flexed position of the interments alone showed them to be Anglo-Saxons.

“Below these secondary graves was an older and far more interesting excavation. Its form and position is shown on the plan at A. At first it was thought to be a huge grave, but as the work proceeded appearances indicating it to have served some other purpose were visible. Its filling-in was peculiar. It consisted of broken chalk, surface soil, and burnt wood, presenting altogether a very unusual arrangement. Along its centre for a distance of about 15 feet were six carbonized uprights of wood, 6 to 9 inches in diameter, at about equal distances and in a row. Wood ashes were also found on the sides and bottom, and scattered in the material filling the excavation.

“Also along the centre many of the large flat pieces of chalk stood on their edges, and at various depths were portions of animal and probably human bone, burnt as well as unburnt, and many fragments of a reddish urn. It was observed that the east end of this excavation became narrower and shallower. It now seemed evident that it was a habitation. Its form, as shown on the (above) plan, was oblong, with a ground floor 25 feet by 4½ feet; and its greatest depth was 6 feet. To its east end was a passage 11 feet long, gradually sloping to the surface.

“”On the south side, commencing at the inner end of the passage and extending inwards for about 12 feet, was a ledge or rock-seat, about 13 inches above the opposite side of the floor, as shown by the dotted lines in the plan and section. The whole width of the floor at the south-west end, for a distance of about 6 feet, was 10 to 12 inches above the centre and lowest part of the floor. The roof of the cave had most probably been formed of horizontal timber, supported by strong uprights of the same material, and then covered with a mound of earth and stones. The roof eventually gave way and the superincumbent earth and stones slid into the dwelling, several of the large flat stones…remaining on their edges.

“The abundance of wood ashes affords unquestionable evidence of the dwelling having been burnt. The preservation of the remains of the six uprights was due entirely to their having been completely charred. The fragments of red pottery are quite plain and belong to three or more vessels, which were probably used for domestic purposes.

“The roof of the cave must have fallen in long previous to the Anglo-Saxon interments, as where the skeletons were found, partly over the cave and partly upon the undisturbed rock, not the slightest distortion was visible, which would have been the case had not the filled-in portion under the bodies become firm. Near the south-side of the dwelling, at about the base of the mound, were several broken human bones and pieces of a dark-coloured urn. Probably these belonged to a disturbed Anglo-Saxon burial.

“We also found in the mound, between the graves E, B, D, a considerable quantity of detached animal and human bones; the latter indicated three or more individuals; a few of the bones showed traces of fire. There were also several small pieces of a dark plain urn.”

Mr Mortimer then commented on the unusual ‘habitation’ section within the mound, not thinking that the dead themselves “lived” here! But we can forgive him this small detail as his work in general was superb. The site was of course a decent East Yorkshire chambered tomb, wherein the dead were laid and, if entrance was ever possible by our tribal ancestors when it was erected, would have paid homage the ancestral figures buried here. Traditional death ceremonies were pretty inevitable I’d say.

References:

- Mortimer, J.R., Forty Years Researches in British and Saxon Burial Mounds of East Yorkshire, Brown & Sons: Hull 1905.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian