Cup-and-Ring Stones: OS Grid Reference – SE 12818 46761

Also Known as:

- Carving no.126 (Hedges)

- Carving no.284 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Fairies Kirk

- Hangingstones

Getting Here

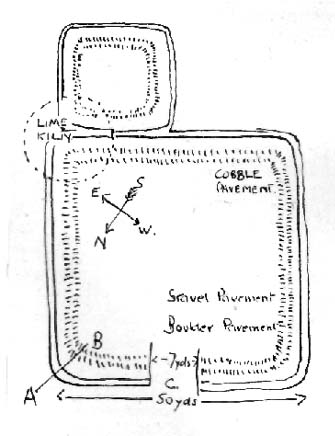

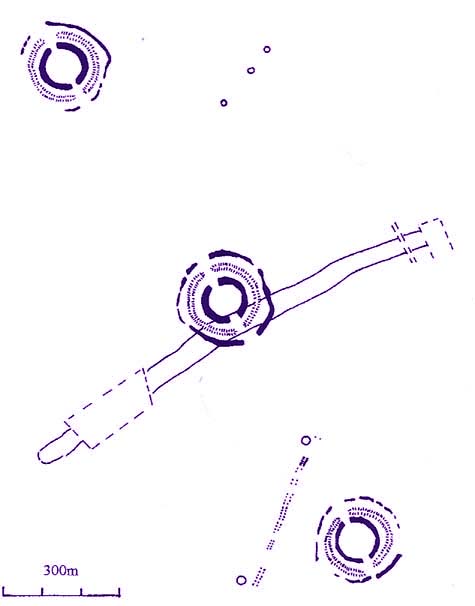

Head up to the Cow & Calf Rocks and walk to the large disused quarry round the back (west). You’ll notice a scattered copse of old pine trees on the edge where the hill slope drops back down towards Ilkley; and there, two raised hillocks (unquarried bits) rise up where the pine trees grow. The carvings are on the flat rocks atop of one of the two hillocks. If you’re walking up from Ilkley, once you’ve crossed the cattle-grid in the road and the moorland slope opens up above you, just walk uphill towards the copse of trees and watch out for the rock outcrop in the picture here.

Archaeology & History

Very well-known to locals, folklorists and archaeologists alike, the remains of these old glyphs have caught the attention of artists, historians and Forteans alike for the images and tales surrounding them. It was obvious that in times past, that the carved remains that we see today would have extended considerably further, but the quarrying destroyed much of it. Indeed, we’re lucky to have this small section of carved rock still intact!

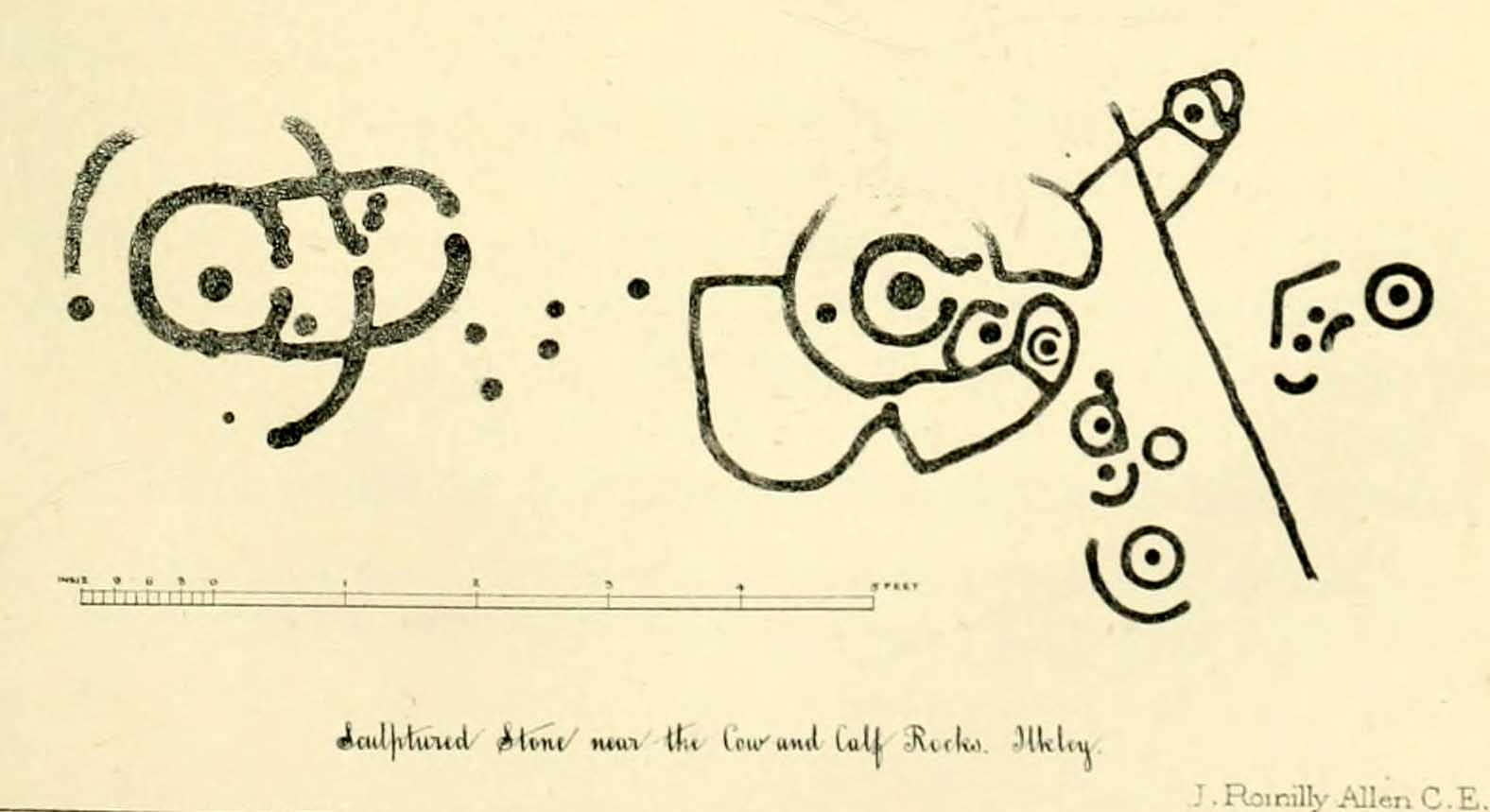

The rocks were first described as the Hanging Stones in the local parish records of 1645, and their name probably derives from the old-english word hangra, meaning ‘a wood on a steep hill-side,’ which is very apt here. The first known description of the site as possessing cup-and-rings appears to have been in a small article in the local Leeds Mercury newspaper in 1871. Several years later J. Romilly Allen (1879) wrote a lengthier descripton of the site:

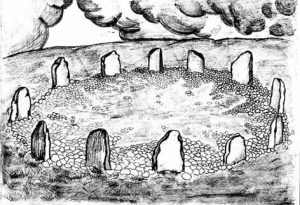

“The crags from which these masses have been detached are known by the name of hanging stones, and at their eastern extremity is a large quarry. Between this quarry and the overhanging edge of the cliff a portion of the horizontal surface of the rock was some years ago bared of turf, thereby disclosing the group of cup and ring sculptures shown on the accompanying drawing. It will be seen that the design consists of twenty-five cups of various sizes, from 1 to 3 inches in diameter. Seven of the cups are surrounded by incomplete rings, many of them being connected by an irregular arrangement of grooves. The pattern and execution are of such a rude nature as almost to suggest the idea of the whole having been left in an unfinished state. The sides of the grooves are not by any means smooth, and would seem to have been produced by a process of vertical punching, rather than by means of a tool held sideways.”

Allen and other archaeologists from this period saw some considerable relevance in the position of this and the many other cup-and-rings along this geological ridge, telling:

“The views obtained from all points over Wharfedale are exceedingly grand, and this fact should not be lost sight of in studying remains that may have been connected with religious observances, of which Nature worship formed a part.”

A common sense point that seemed long-lost to many archaeologists, adrift as they went in their measurements of lithics and samples of data charts for quite a number of years. In recent years however, this animistic simplicity has awakened again and they’ve brought this attribute back into their vogue. Let’s hope they don’t lose sight of it again!

There are tons of other archaeological references to this fine set of carvings, but none add anything significant to anyone’s understanding of the nature of the designs. We must turn to psychoanthropology, comparative religion and folklore if we want to even begin making any realistic ‘sense’ (if that’s the right word!) of this and other cup-and-rings. Curiously, the nature of this and other carvings is a remit archaeology has yet to correctly engage itself in.

On a very worrying note, we need to draw attention to what amounts to the local Ilkley Parish Council officially sanctioning vandalism on the Hanging Stones, other prehistoric carvings and uncarved rocks across Ilkley Moor. As we can see on a couple of photos here, recent vandalism has been enacted on this supposedly protected monument. Certain ‘officials’ occasionally get their headlines in the local Press acting as if they’re concerned about the welfare of the ancient monuments up here, but in all honesty, some of them really don’t give a damn. The recent vandalism on this stone and others has now been officially recognised as an acceptable “tradition” and a form of — get this! — “twentieth / twenty-first century informal unauthorised carving” and has been deemed acceptable by Ilkley Parish Council as a means to validate more unwanted carving on the moorland “in the name of art”! Of course, their way of looking at this has been worth quite a lot of money to a small group of already wealthy people. But with Tom Lonsdale and Ilkley Council validating or redesignated ‘vandalism’ as “twenty-first century informal unauthorised carvings”, this legitimizes and encourages others to follow in their shallow-minded ignorant footpath, enabling others with little more than a pretentious ‘care’ for both environment and monuments to add their own form of ‘art’ on cup-and-ring carvings, or other rocks on the moors.

You can see in some recent vandalism — sorry, traditional “twentieth / twenty-first century informal unauthorised carving” — at the top-right of the Hanging Stones photo to the side, a very ornate ‘Celtic’-style addition, akin to the quality carved by well-known stone-mason Pip Hall who, coincidentally, has now been granted a lot of money to “officially” carve her own work on another stone further down the valley from here. With Miss Hall, Mr Lonsdale, poet Simon Armitage and Ilkley Parish Council each playing their individual part in encouraging what is ostensibly vandalism…errr…sorry – I keep getting it wrong – I mean traditional “twentieth / twenty-first century informal unauthorised carving” on the Hanging Stones monument and other cup-and-ring stones on the moor, we can perhaps expect a growth industry in this field…..especially if you’re wanting to make more money for yourself in the name of art or poetry. And if you apply to Rachel Feldberg of the Ilkley Arts Festival, you may get good money for your work… Seriously! (this is no joke either)

Please contact Ilkley Parish Council and other relevant authorities and express your dismay at their lack of insight and concern for the knock-on effects of their decisions on this matter. Other plans to infringe even further onto Ilkley Moor are in the business pipeline…

Folklore

Just underneath the carved overhanging rocks (walk off the knoll to the bottom of the rocks, facing the town), is a small recess or sheltered cavity which, told Harry Speight (1900),has

“From time immemorial (been) known as ‘Fairies’ Kirk’, and traditions of it having been tenanted by those tiny sprites, the fairies, still exist among old people in the neighbourhood.”

Tradition goes on to tell that when the Saxons arrived here, they were wont to build a christian church by the Hanging Stones, but the little people strongly resented this and fought hard against the invading forces. As the Saxons started building the edifice of the new religion, during the night the fairy folk took down the stones and moved them into the valley below. In the morning when the Saxons found this had happened, they carried the stones back up to begin building again; but each night, the fairy folk emerged and again took the stones to the valley bottom again. Eventually, after much hardship, the Saxon folk gave up the idea of building on the Fairie’s Kirk, as it was known, and the church that still remains in Ilkley centre was decided as an easier place to build their edifice.

Traditions such as this (of fairies moving stones back to whence they came, or away from ancient archaeological sites) are found throughout Britain and appear to be simple representations of the indigenous peasant hill-folk who strongly objected to their own sacred sites (rocks, trees, wells, etc) being supplanted by the invading religious force.

In more recent years the observation of curious light phenomena over these rocks have been seen, both over here and the Cow & Calf Rocks…

References:

- Allen, J.R., ‘The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,’ in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, vol.35, 1879.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milveton 2001.

- Bogg, Edmund, Higher Wharfeland, James Miles: Leeds 1904.

- Collyer, Robert & Turner, J. Horsfall, Ilkley: Ancient and Modern, William Walker: Otley 1885.

- Gelling, Margaret, Place-Names in the Landscape, Phoenix: London 2000.

- Hedges, John (ed.), The Carved Rocks of Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Leeds Mercury, ‘Prehistoric Remains at Ilkley’, 20 April, 1871.

- Michell, John, The Earth Spirit: Its Ways, Shrines and Mysteries, Thames & Hudson: London 1975.

- Size Nicholas, The Haunted Moor, William Walker: Otley 1934.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Name Elements – volume 1, Cambridge University Press 1956.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian