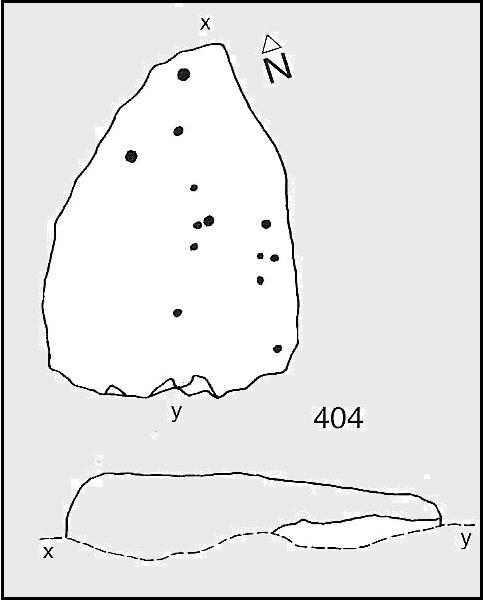

Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – SJ 24474 84933

Also Known as:

- Thor’s Rocks

Archaeology & History

On Thurstaston Common a 298 foot high hill has a large red sandstone outcrop, on the landward side, known as Thor’s Stone. One large rectangular block of stone that is 50 feet in length, 30 feet wide by 25 foot high has been eroded over thousands of years. Described by J.A. Picton in 1877 as “the Great Stone of Thor,” the village itself seemed to have gained its name from this prominent mass of rocks. It was described first of all in the Domesday book, as Turstanetone, and both village and rocks have been written as variants on the original ever since. The place-names writers Mills & Room (1998) ascribe the name to being a “farmstead or village of a man called Thorstein”; but it’s just as likely to derive from “a farmstead of/at Thor’s Stone.” (Harrison 1898) As early landscape features were traditionally equated with animistic and mythic lore, the Viking god Thor is more probable than some unlikely chap called Thorstein.

More than 100 miles southeast of here, we find another Thor Stone in the village of Taston, showing similar megalithic etymology.

Folklore

Local folklore tells that the rock is named after the Norse god Thor – he who causes thunder and lightning. Viking settlers from Thingwell apparently settled here in the 10th century AD and, according to legend, these settlers used the stone as a pagan altar with blood sacrifices taking place here. A creation myth of the site tells that Thor tossed the large stone here in anger; and yet another says that the stone was raised here to commemorate the battle of Brunanburh in 937 AD. In modern more times, Morris dancers meet here and enact their rites on Mayday mornings.

The outcrop has been eroded away over thousands of years by the weather, post glacial erosion and even quarrying, leaving strange shapes, features and projections in the soft sandstone. There is much recent graffiti to be seen all over the rock, especially on the summit and sides including one set of graffiti carved by Professor Taylor in 1879. There used to be a “fairy well” near the stone but this disappeared long ago. Children took flowers to the well to decorate it, while adults visited it to receive a cure for various ailments of the body. At nearby Thurstaston Hall, Christina Hole (1937) reported there lived the ghost of a troubled woman.

References:

- Harrison, Henry, The Place-Names of Liverpool, Elliot Stock: London 1898.

- Hole, Christina, Traditions and Customs of Cheshire, Williams & Norgate: 1937.

- Mills, A.D. & Room, Adrian, A Dictionary of English Place-Names, Oxford University Press 1998.

© Ray Spencer, The Northern Antiquarian