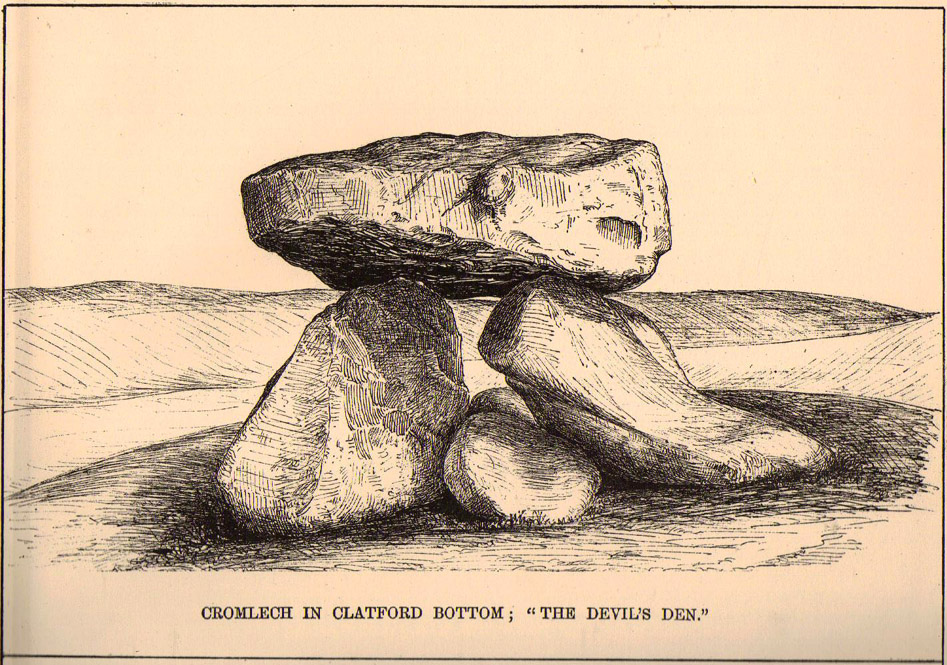

Cromlech: OS Grid Reference – SU 15209 69651

Also Known as:

- Devils Den

- Dillion Dene

When Pete Glastonbury brought us here, we walked east out of the Avebury stone circle and up the Wessex Ridgeway track. When you hit the “crossroads” at the top of the rise a mile along, go across the stile into the grasslands for a few hundred yards till you hit the obviously-named “Gallops” racecourse-looking stretch. Walk down for a few hundred yards till you hit a footpath on your left that takes you across and down grasslands that takes you slowly into the valley bottom. You’re damn close!

Otherwise (and I aint done this route!), walk up the footpath straight north from Clatford village, up the small valley for about 1km. You’ll eventually see this great stone heap in the field on your left!

Archaeology & History

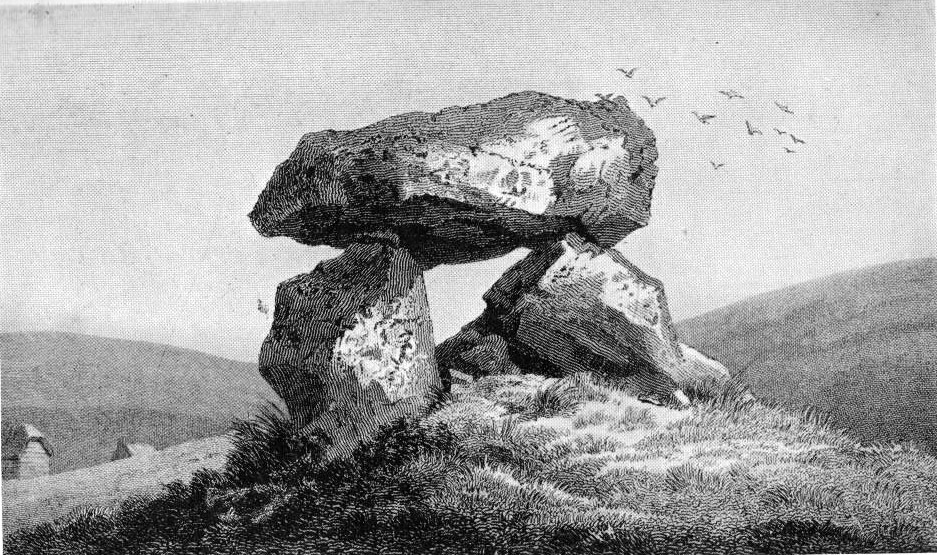

I was brought here one fine day last year in the company of PeteG (our guide for the day), Geoff, June and Mikki Potts. Twas a fine foray exploring the various prehistoric sites on the lands east of Avebury — but it was my very first venture to this site, the Devil’s Den — and a grand one it was indeed! Standing close to the small valley bottom a couple of miles east of the great stone circle, this megalithic monument is thought to be neolithic in origin.

When H.J. Massingham (1926) came here, the day and spirit of the place must have felt fine, as he described,

“its three uprights and capstone stand forlornly in the midst of an alien sea of ploughland swinging its umber ripples to the foot of a stone isle, drifted nearly four thousand years from the happy potencies of its past.”

And, on many good times here no doubt, for many people, such feelings still hold…

It was described by the President for the Council of British Archaeology, Paul Thomas (1976), “as a setting of four sarsen uprights with a capstone”, whereby four uprights have not been noticed here since very early times. Not sure how old he was though! Today the very large capstone weighing upwards of 20 tons rests gently upon just two very bulky upright monoliths. A third is laid amidst the great tomb , overgrown and sleepy, touching one of the two uprights….

The cromlech itself seems to have once been part of a lengthy mound that was covered in earth, “about 230ft long and 120ft broad, now virtually removed by ploughing.” On top of the great capstone are at least two cup-markings: one of them with a possible oval-shaped line carved out onto the edge of the rock (similar to the C-shaped carving on the nearby Fyfield Down cup-marked stone), but this needs looking at in various lights so we can ascertain whether it has a geological or artificial origin.

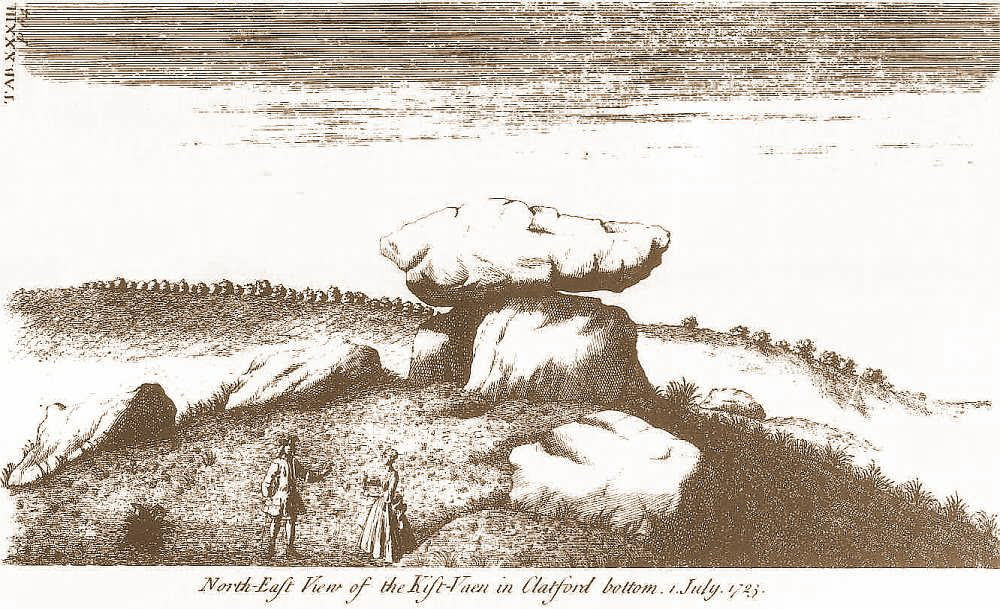

Suggested by Edwin Kempson (1953) and also by Aubrey Burl (2002) and other dialect and place-name students to have originally been called Dillion Dene — “the boundary marker in the valley” — this collapsed chambered tomb has had many literary visitors, from William Stukeley onwards. When the reverend Smith wrote his great tome in 1885, he gave an assessment of those who came before him, saying:

“This is a noble specimen of the Kistvaen: it stands erect in its original position, only denuded of the mound of earth which, I venture to say (on the authority of the Rev. W.C. Lukis and others best acquainted with these remains) at one time invariably covered them: and this massive erection of ponderous stones is known as the ‘Devil’s Den’, and offers an exceedingly fine specimen of the kistvaen to those who have not made the acquaintance of these ancient sepulchres in other counties. It is not only perfect in condition, but of very grand dimensions; moreover, it is well known to everybody who takes the slightest interest in Wiltshire antiquities… Stukeley says very little of this kistvaen, though he gives several plates of it (in Abury Described), his only remark being: “An eminent work of this sort in Clatford Bottom, between Abury and Marlborough.” Sir R. Hoare (in Ancient Wiltshire, North) is more enthusiastic, he says: “From Marlborough I proceed along the turnpike road as far as the Swan public house in the parish of Clatford, and then diverge into the fields on the right, where, in a retired valley amongst the hills, is a most beautiful and well-preserved kistvaen, vulgarly call’d the ‘Devil’s Den.’ It has been erroneously described as a cromlech. From the elevated ground on which this stone monument is placed, it is evident that it was intended as a aprt annexed to the sepulchral mound, and erected probably at the east end of it, according to the usual custom of primitive times.””

In more recent years, Terence Meaden (1999) has suggested that the Devil’s Den may actually have been a simple cromlech and never had any covering mound of earth. In his Secrets of the Avebury Stones he described how,

“The vertical megaliths must have been set up firmly first and then, quite possibly, a mound was raised outside and between them. A very long ramp could have been built next, along which the capstone was dragged until it lay on top of the vertical monoliths, after which both mound and ramp would be removed as far as possible. Such an operation, if correct, would explain why the stones of Devil’s Den now stand on an obviously artificial eminence; and why the much-spread remains of a long mound oriented NW-SE, about 70 metres (230 feet) long and 40 metres (130 feet) broad, were seen and described by Passmore in 1922. One should not necessarily assume that the stones are the remains of a chambered long barrow, although they might be.”

And you’ve gotta say that unless we have hardcore evidence to the contrary, his summary is quite possible. However, it seems here that Meaden has simply utilised this logic to enable him to posit another reason — a “good one” he calls it — for this suggestion, i.e.,

“its capstone seems to have profiles of heads carved upon two, perhaps three of its sides; suggesting that, if the art was meant to be seen, the capstone was never covered with earth.”

Unfortunately however, these possible “carved heads” on the sides of the capstone more typify Rorscharch responses to natural geological shapes scattering rocks all over the planet. Up North, if we were to attempt this sorta suggestion, we’d have millions of such carved heads popping up all over the place. It’s a nice idea, but somewhat unlikely.

Folklore

The old dowser Guy Underwood (1977) was renowned for locating water lines* in and around many of England’s prehistoric sites, and the same pattern was recorded here. He told that the Devil’s Den marked the site of a blind spring “of exceptional importance.” He continued:

“The Devil’s Den dolmen marks the source of a multiple water line which forms a maze, marked by stones, about 200 yards to the northwest. It terminates at a well, where two tracks cross about a mile further west. This site is likely to have had special sanctity and would be interesting to excavate.”

Whilst the importance of water was understandable in ancient days, some other folklore attributes derive from quite different ingredients. The common theme of “immovability” is found here, as described by reverend Smith (1885) again who, amidst other peculiarities, told the following:

“There are various traditions connected with it. I was told some years since, by an old man hoeing turnips near, that if anybody mounted to the top of it, he might shake it in one particular part. I do not know whether this is the case or not, though it is not unusual where the capstone is upheld by only three supporters. But another labourer whom I once interrogated informed me that nobody could ever pull off the capstone; that many had tried to do so without success; and that on one occasion twelve white oxen were provided with new harness, and set to pull it off, but the harness all fell to pieces immediately! As my informant evidently thought very seriously of this, and considered it the work of enchantment, I found it was not a matter for trifling to his honest but superstitious mind; and he remained perfectly unconvinced by all the arguments with which I tried to shake his credulity.”

References:

- Burl, Aubrey, Prehistoric Avebury, Yale University Press 2002.

- Goddard, E., “The Devil’s Den, Manton, Wiltshire,” in The Antiquaries Journal, volume 2, no.1, January 1922.

- Gomme, Alice B., ‘Folklore Scraps from Several Localities’, in Folklore, 20:1, 1909.

- Grinsell, Leslie V., Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain, David & Charles: London 1976.

- Kempson, E.G.H., “The Devil’s Den,” in Wiltshire Archaeology & Natural History Magazine, 55, 1953.

- Massingham, H.J., Downland Man, Jonathan Cape: London 1926.

- Meaden, Terence, The Secrets of the Avebury Stones, Souvenir Press: London 1999.

- Smith, A.C., A Guide to the British and Roman Antiquities of the North Wiltshire Downs, Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society 1885.

- Thomas, Nicholas, Guide to Prehistoric England, Batsford: London 1976.

- Underwood, Guy, The Pattern of the Past, Abacus: London 1977.

- Wright, Joseph, English Dialect Dictionary – volume 2, Henry Frowde: London 1898.

* Those people who allege they can dowse will always find water in their first few months, if not years, of sensitivity. There is a pattern nowadays of people using dowsing tools and, when the rods cross (or whichever accessory they get their reactions from), they allege they are connecting with unknown energies, ley lines and other such items; but this is simply incorrect. The primary dowsing response is water (life-blood) and it takes much practice over long periods of time to even begin isolating leys or other occult phenomena.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian