Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – NN 89532 30595

Also Known as:

- Cairn Ossian

- Canmore ID 25554

- Clach-na-Ossian

- Clach Ossian

- Giant’s Grave

- Ossian’s Grave

- Soldier’s Grave

There are two ways into this glen by road. Whichever route you take (from Crieff side, or via the long Dunkeld route), when you hit the flat bottom of it, where the green fields are right by the roadside, walk along till you find the road meets the river’s edge. On the south-side of this small roadside section of the river, you’ll see a single large boulder 10-20 yards away. That’s the spot!

Archaeology & History

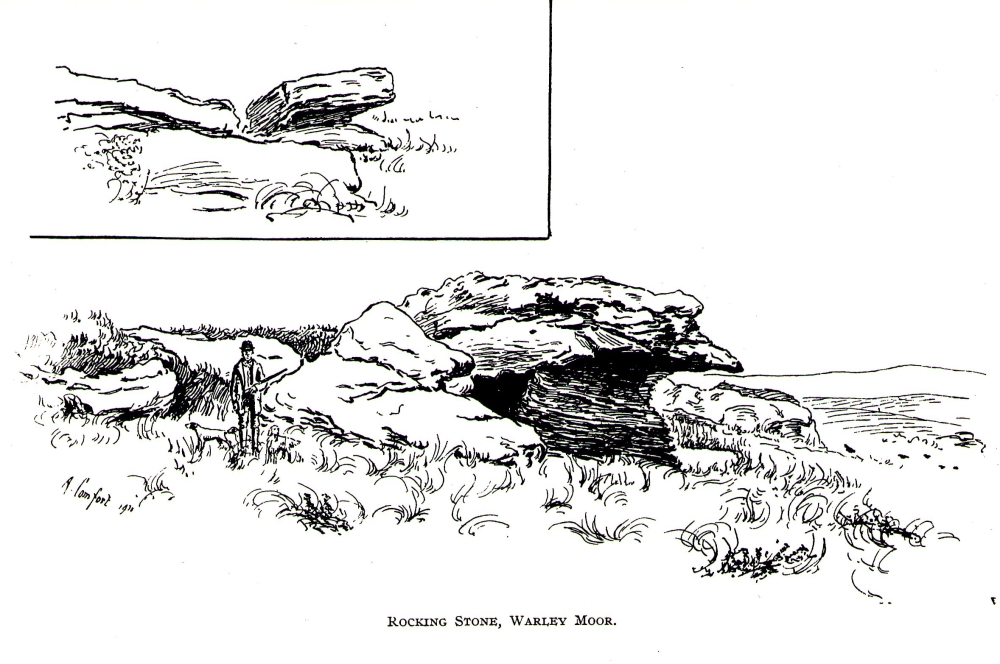

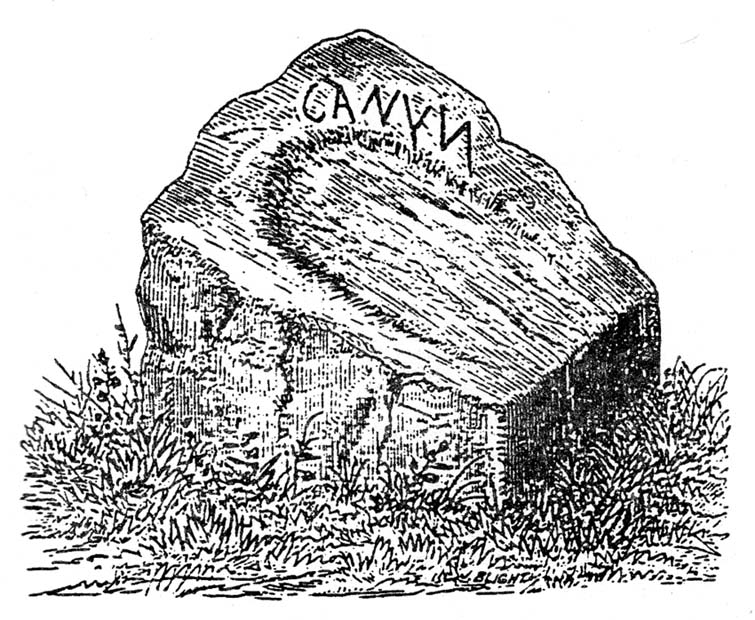

Described in some of the archaeology texts as just a ‘cist’, this giant stone is obviously the remains of much more. For a start, as the 1834 drawing illustrates here (coupled with several other early descriptions of the place), other visible antiquarian remains were very much apparent at Ossian’s Stone before a destructive 18th century road-laying operation tore up much of this ancient site. A marauding General Wade of the English establishment was cutting through the Scottish landscape a “military road”, to enable the English to do the usual “civilize the savages”, as they liked to put it. This curious “Giant’s Grave” was very lucky to survive.

The earliest description of events surrounding the site, as well as the attitude of the Highlanders when they saw the disrespectful English impose their usual disregard, is most insightful. In a series of letters written by a Captain Edward Burt (1759) in the first-half of the 18th century to the english monarch of the period, we read a quite fascinating account which must have been very intriguing to witness first-hand.

General Wade and his band of marauders had reached the Sma’ Glen at the end of Glen Almond and were about to continue the construction of their road. Burt (1759) wrote:

“A small part of the way through this glen having been marked out by two rows of camp colours, placed at a good distance one from another, whereby to describe the line of the intended breadth and regularity of the road by the eye, there happened to lie directly in the way an exceedingly large stone; and, as it had been made a rule from the beginning, to carry on the roads in straight lines as far as the way would permit, not only to give them a better air, but to shorten the passenger’s journey, it was resolved the stone should be removed, if possible, though otherwise the work might have been carried along on either side of it.

“The soldiers, by vast labour, with their levers and jacks, or hand-screws, tumbled it over and over till they got it quite out of the way, although it was of such an enormous size that it might be matter of great wonder how it could ever be removed by human strength and art, especially to such who had never seen an operation of that kind: and, upon their digging a little way into that part of the ground where the centre of the base had stood, there was found a small cavity, about two feet square, which was guarded from the outward earth at the bottom, top, and sides, by square flat stones.

“This hollow contained some ashes, scraps of bones, and half-burnt ends of stalks of heath; which last we concluded to be a small remnant of a funeral pile. Upon the whole, I think there is no room to doubt but it was the urn of some considerable Roman officer, and the best of the kind that could be provided in their military circumstances; and that it was so seems plainly to appear from its vicinity to the Roman camp, the engines that must have been employed to remove that vast piece of a rock, and the unlikeliness it should, or could, have ever been done by the natives of the country. But certainly the design was, to preserve those remains from the injuries of rains and melting snows, and to prevent their being profaned by the sacrilegious hands of those they call Barbarians, for that reproachful name, you know, they gave to the people of almost all nations but their own.

“…As I returned the same way from the Lowlands, I found the officer, with his party of working soldiers, not far from the stone, and asked him what was become of the urn? To this he answered, that he had intended to preserve it in the condition I left it, till the commander-in-chief had seen it, as a curiosity, but that it was not in his power so to do; for soon after the discovery was known to the Highlanders, they assembled from distant parts, and having formed themselves into a body, they carefully gathered up the relics, and marched with them, in solemn procession, to a new place of burial, and there discharged their fire-arms over the grave, as supposing the deceased had been a military officer.

“You will believe the recital of all this ceremony led me to ask the reason of such homage done to the ashes of a person supposed to have been dead almost two thousand years. It did so; and the officer, who was himself a native of the Hills, told me that they (the Highlanders) firmly believe that if a dead body should be known to lie above ground, or be disinterred by malice, or the accidents of torrents of water, &c. and care was not immediately taken to perform to it the proper rites, then there would arise such storms and tempests as would destroy their corn, blow away their huts, and all sorts of other mis-fortunes would follow till that duty was performed. You may here recollect what I told you so long ago, of the great regard the Highlanders have for the remains of their dead…”

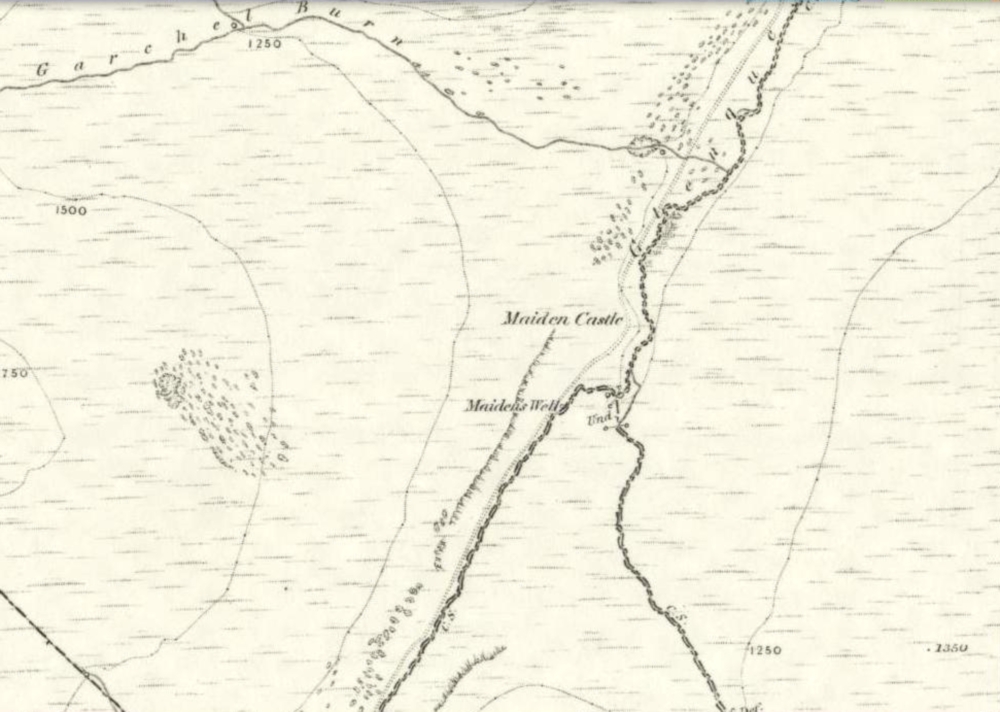

We can rest assured that the ‘Roman officer’ idea proclaimed by our early narrator is most probably wrong and that the nature of this site, when seen at ground-level even today and moreso by referencing Skene’s 1834 drawing of the place, above (which shows a more complete low surrounding ring of stones) indicate this to be of prehistoric provenance. Of intrigue to me, is the ritual of the incoming Highlanders, who took the relics onto another place and re-interred them in their own customary manner. We do not know where the Highlanders moved these (probable) prehistoric relics and I can find no supporting folklore to show precisely where they went—but a likely site would be the prehistoric cairn on the mountaintop southwest of here (at NN 8899 3018), or a site that has sometimes been confused with Ossian’s Stone a short distance to the south in the Sma’ Glen, known as the Giant’s Grave (at NN 9050 2956). This latter site would seem more probable.

Anyway…. many years after Edward Burt’s initial Letters defined the site for outsiders, one Thomas Newte (1791) came a-wandering hereby. He found that the account of General Wade’s intrusion was still on the tongues of local people, along with additions of further giant-lore and Fingalian tales, typical of the Creation myths of our early ancestors. In typically depreciative English manner Newte told:

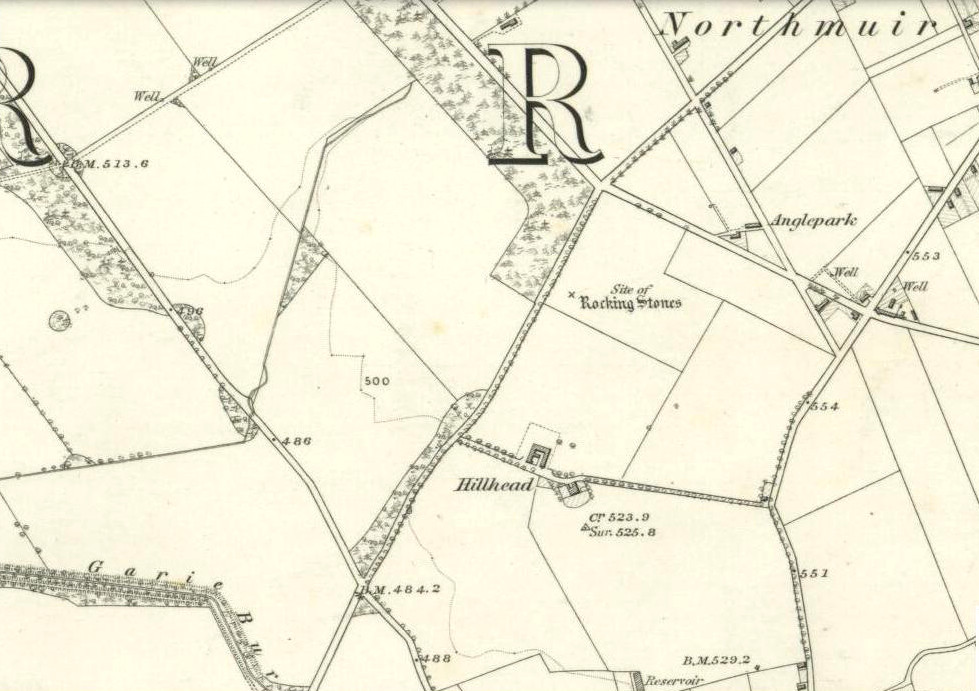

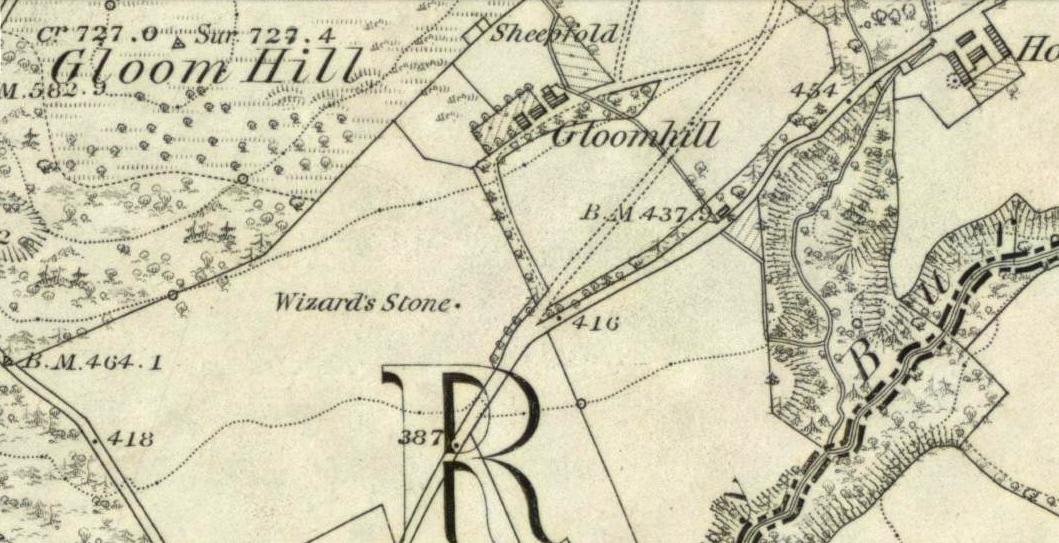

“In that awful part of Glen Almon, already mentioned, where lofty and impending cliffs on either hand make a solemn and almost perpetual gloom, is found Clachan-Of-Fian, or monumental Stone of Ossian. It is of uncommon size, measuring seven feet and an half in length, and five feet in breadth. About fifty years ago, certain soldiers, employed under General Wade in making the Military Road from Stirling to Inverness, through the Highlands, raised the stone by large engines, and discovered under it a coffin full of . This coffin consisted of four gray stones, which still remain, such as are mentioned in Ossian’s Poems. Ossian’s Stone, with the four gray stones in which his are said to have been deposited, are surrounded by a circular dyke, two hundred feet in circumference, and three feet in height. The Military Road passes through its centre.”

From hereon, many other writers and travellers came to see this great legendary stone within the depleted remains of its embanked circle—and thankfully it hasn’t been disturbed any further, still being visible to this day. The greatest ‘archaeological’ attention the site has received was from the early pen of great antiquarian Fred Coles (1911). On his journey here, after travelling past a large white stone which was mistakenly named as Ossian’s Stone by the usual contenders, he and his friend reached the right place:

“close to a strip of ground where the river and road almost touch each other, and immediately below the steepest of the crags of Dun More on the eastern side and the debris slopes of Meall Tarsuinn on the west, a most impressive environment, be the stone a prehistoric monument or not! The spot is interesting for itself, apart from all legend; and the remains consist of a mighty monolith…and a narrow grassy mound…to its east, with a few earthfast blocks set edgewise near its eastern extremity. Close to the roadside, but at the same level of 690 feet above the sea, there is a slab-like stone set up, measuring 3 feet in width, 1 foot 3 inches in thickness, and about 2 feet 6 inches in height. A space of 63 feet separates this block…from the huge rhomboidal mass called Ossian’s Stone. Five feet east of the latter is the base of the grassy mound which measures about 12 feet in length, 4 feet in greatest breadth, and 3 feet 10 inches in height. To the north and the south in a slightly curving line are set the six small slabs shown. There seems also to be a vague continuation of this strange alignment in both directions. All over the ground between A and B, are many strangle low parallel ridges of smallish stones having a general direction of nearly north and south. The rest of the ground is grassy, and here and there a little stony. In the plan all the stones are drawn larger than exactly to scale.

“The great stone is 8 feet high and has a basal girth of 27 feet. Several small stones lie near it. Such are the facts as at present to be observed on the ground.”

There are two small conjoined cup-marks on top of the stone, but these seem to be geological in nature. The precise nature of the site is difficult to ascertain without excavation; but the Royal Commission lads reckon it to be a prehistoric ‘cist’ or grave in their own analysis, based mainly on the quoted literary texts. The surrounding ‘ring’ of small stones doesn’t seem to have captured their attention too much; but the site needs contextualizing within this damaged circular enclosure, which appears to have been a cairn circle initially, of some sort, with Ossian’s huge stone resting over the grave of one late great ancestral character, probably placed here thousands of years back in the Bronze Age… A truly fascinating place in truly gorgeous landscape.

Folklore

The glen itself has a scattering of giant lore associated with Finn and/or Ossian. A nearby cave was one of the places where this legendary character, and subsequent bards, were said to have spent time.

There are a small number of heavy rocks presently placed on top of Ossian’s Stone. These may be due to the site being used as a “lifting stone”: a sort of rite of passage found at a number of sites in the Perthshire mountains and across the Highlands to indicate a boy’s strength before entering manhood. Not until they have lifted and deposited a very heavy rock onto the boulder can they rightly become chief or leader, etc.

The poet William Wordsworth wrote about Ossian’s Stone, calling it “Glen Almein, or The Narrow Glen”:

In this still place, remote from men,

Sleeps Ossian, in the Narrow Glen;

In this still place, where murmurs on

But one meek streamlet, only one:

He sang of battles, and the breath

Of stormy war, and violent death;

And should, methinks, when all was past,

Have rightfully been laid at last

Where rocks were rudely heaped, and rent

As by a spirit turbulent;

Where sights were rough, and sounds were wild,

And everything unreconciled;

In some complaining, dim retreat,

For fear and melancholy meet;

But this is calm; there cannot be

A more entire tranquillity.

Does then the Bard sleep here indeed?

Or is it but a groundless creed?

What matters it? I blame them not

Whose Fancy in this lonely Spot

Was moved; and in such way expressed

Their notion of its perfect rest.

A convent, even a hermit’s cell,

Would break the silence of this Dell:

It is not quiet, is not ease;

But something deeper far than these:

The separation that is here

Is of the grave; and of austere

Yet happy feelings of the dead:

And, therefore, was it rightly said

That Ossian, last of all his race!

Lies buried in this lonely place.

References:

- Anonymous, Tourists Guide to Crieff, Comrie and the Vale of Strathearn, Crieff

1874. - Burt, Edward, Letters from a Gentleman in the North of Scotland – volume 2, L.Pottinger: London 1759.

- Coles, F.R., “Report on stone circles in Perthshire principally Strathearn,” in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 45, 1911.

- Finlayson, Andrew, The Stones of Strathearn, One Tree Island: Comrie 2010.

- Gordon, Seton, Highways and Byways in the Central Highlands, MacMillan Press 1948.

- Holder, Geoff, The Guide to Mysterious Perthshire, History Press 2006.

- Hunter, John, Chronicles of Strathearn, David Philips: Crieff 1896.

- Macara, Duncan, Guide to Crieff, Comrie, St Fillans and Upper Strathearn, Edinburgh 1890.

- Macculloch, James, The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland, London 1824.

- Marshall, William, Historic Scenes in Perthshire, Edinburgh 1881.

- McKerracher, Archie, Perthshire in History and Legend, John Donald: Edinburgh 1988.

- Newte, Thomas, Prospects and Observations on a Tour in England and Scotland: Natural, Oenomical and Literary, G.G.J. Robinson: London 1791.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks again to Paul Hornby for his assistance with site inspection, and additional use of his photos.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian