Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 54125 35388

Also Known as:

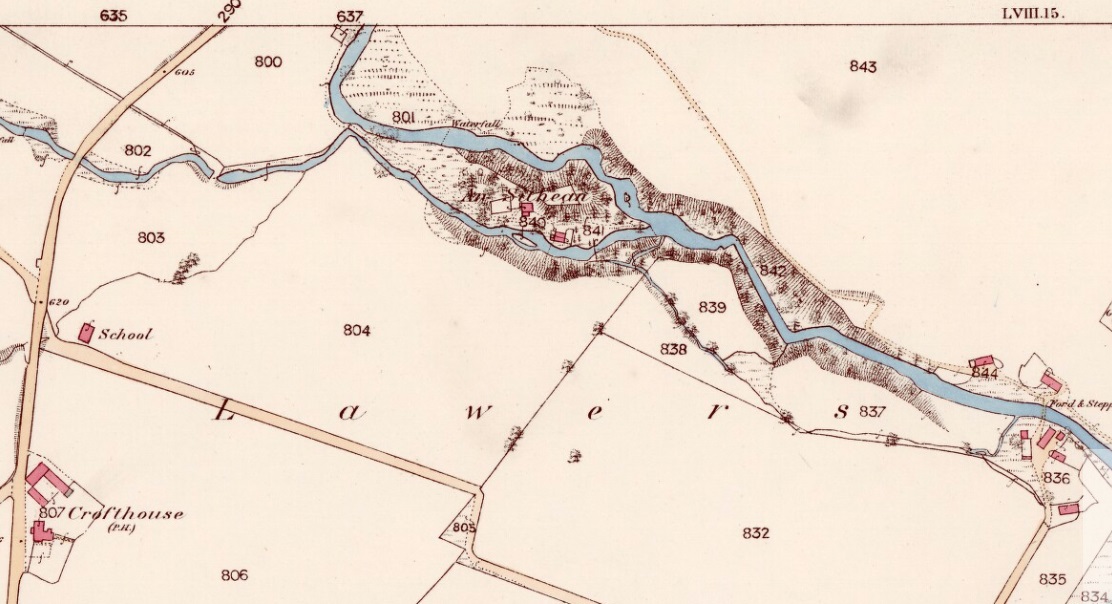

Going out of Killin towards Kenmore on the A827 road, immediately past the Bridge of Lochay Hotel, turn left. Go down here for just over 2 miles and park-up where a small track turns up to the right, close to the riverside and opposite a flat green piece of land—right by The Green cup-marked rock-face. Walk up the small bendy track for about ⅔-mile (1km) and eventually, high above the tree-line, the road splits. Right here, go through the gate and walk downhill, over the boggy land, cross the burn, then the overgrown wall, and a second overgrown wall. Very close hereby is a small rise in the land amidst the mass of bracken, upon which is the stone in question!

Archaeology & History

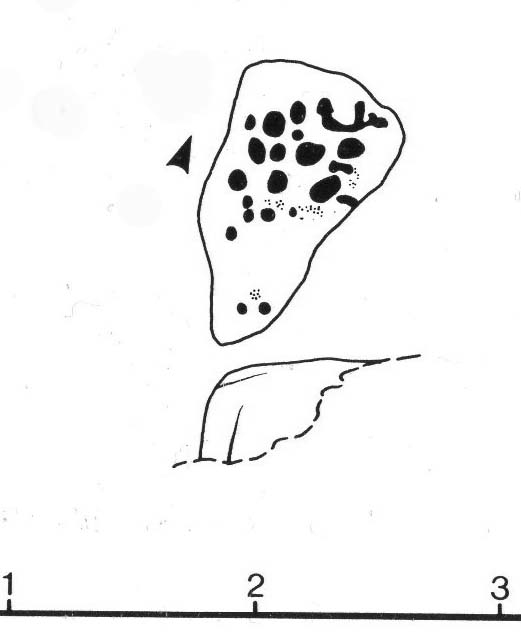

This large long, undulating, quartz-rich stretch of rock has two main petroglyphic sections to it, with curious visual sections of natural geological forms accompanying the cup-markings, found either side of the stone on its north and south sides. Its northern face has at least 20 cup-marks, of differing sizes, measuring between one and two inches across and up to half-an-inch deep. Their visual nature is markedly different to those on the more southern side of the stone, where they are generally smaller and much more shallow, perhaps meaning they were carved much earlier than their northern counterparts. One of the cups on this section has a very faint incomplete ring around it.

Running near the middle of the rock is a large long line of quartz and a deep cleft in which I found a curious worked piece of quartz shaped like a large spear-head, and another that looks like it’s been deliberately smoothed all round the edges. Both these pieces fit nicely in my hand. All around the edges of the stone, many tiny pieces of quartz were scattered, as if they had been struck onto the stone—either to try carving the cups (damn problematic!), or for some visual/magickal reason.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian