Sacred Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 4573 9180

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 43475

- Saintmaha Well

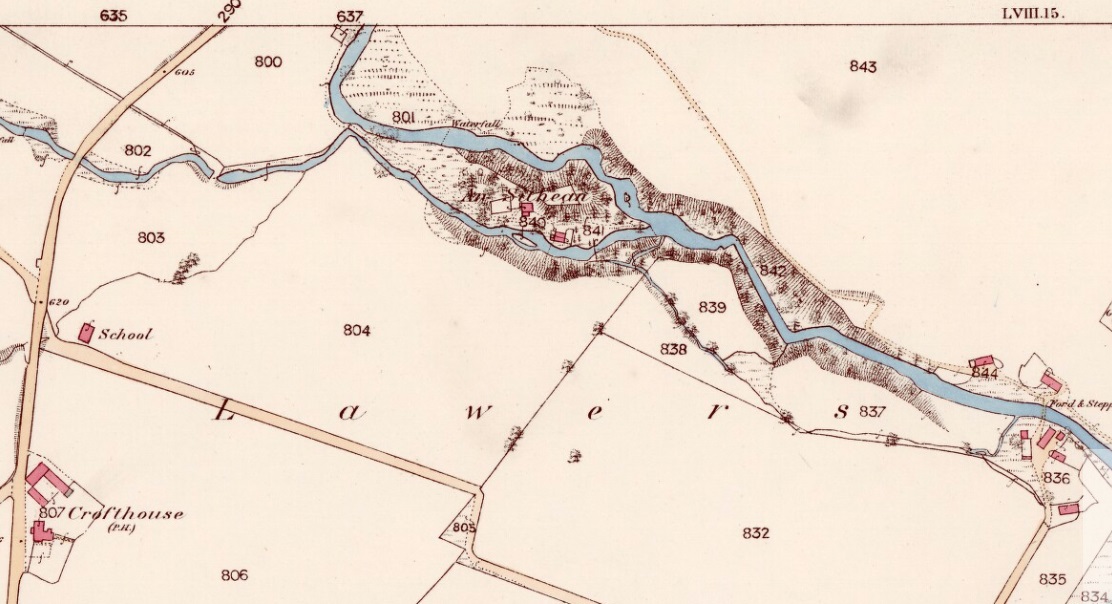

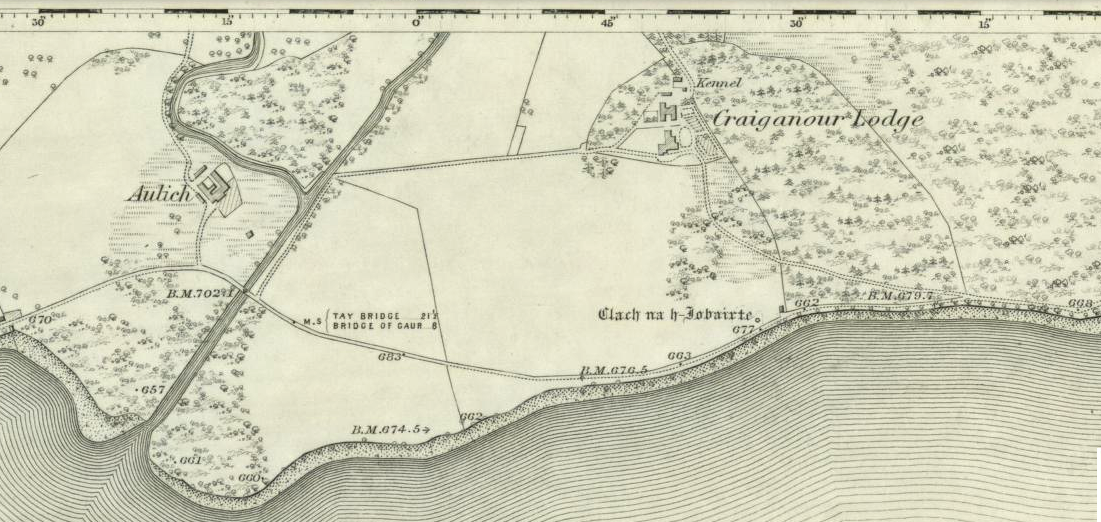

Bittova walk to reach this one. From The Square in Drymen village, take the long Old Gartmore Road north for 1.4 miles (2.25km) until you reach the West Highland Way track. Turn left and walk along the track for 1.75 miles (2.8km), making sure that you note crossing the large burn as a guide before your next turn, right, uphill and further north. About 400 yards up, you emerge from the forestry plantation and onto the open moorland. Walk about 200 yards (185m) up the track then walk left, right into the boggy moorland. Keep your eyes peeled for a small standing stone on the heath about 130 yards along, and just below this is a stone-lined spring of water.

Archaeology & History

This little-known healing spring of water, high upon the moors overlooking the southern isles of Loch Lomond and the mountains beyond, is in a beautiful (if boggy) setting. We visited here on a somewhat wet day, amidst a wealth of Nature’s downpours in previous days giving us the masks of grey overcast skies and soaking grounds. Despite this, the setting is gorgeous and, if we’d have visited on a sunny day, the feel and views would be outstanding. This mighthave been one of the reasons that this particular spring of water was chosen to be sanctified. Certainly it has an ancient history, if christian tales are anything to go by…

Although listed in the parish of Buchanan, the well resides on the hills above the village of Balmaha more than 2 miles to the west, on the shores of Loch Lomond; and Balmaha is thought to have its origins enwrapped with an early christian characters of some prominence. The element maha derives, said Watson (1926) from the Scottish Gaelic ‘Mo-Thatha’, from the earlier Irish name Tua, meaning “the silent one.” The character known as St. Maha gives his name to the village and according to H.G. Smith (1896),

“Bal maha may most probably retain the memory of St Mochai or Macai; Latin, Maccaeus, also known as St Mahew, a companion to St Patrick, to whom the church of Kilmahew in Cardross was dedicated. Mahew lived at Kingarth in Bute, and Buchanan formed part of the district superintended by Kingarth. He was a poet, physician, and noted in his day for his mathematical learning… (St Mahew’s day was 11 April).”

It seems therefore probable that this poet-healer character underlies the old name at this well. St. Maha’s attributes as a poet and healer would suggest he was trained in archaic techniques before declaring himself as ‘christian.’ In the landscape nearby are other early Irish christian traditions, pasted onto much earlier heathen ingredients.

When Mr Smith (1896) wrote about the well, the remains of an old tree still grew above the waters onto which local people left memaws and offerings for the resident spirit, maintaining the animistic traditions of popular culture that still endure. He wrote:

“St Maha’s Well is in an upper field of the farm of Crietihall. It was of old a healing well, and in the memory of man pieces of cloth used to be fastened to a tree which overshadowed it, votive offerings by the pilgrims who sought the saint’s favour.”

…Although in truth, “the saint’s favour” is mere window dressing for the more archaic and natural feel of the site: what John Michell (1975) would have termed the “resident Earth spirit.”

The well is surrounded by a small arc of stone masonry, which the ever-reliable Royal Commission (1963) lads tell us, “measures 2ft by 3ft internally and stands about 1ft above the surface of the water.” Just above the well itself is a small rise with a standing stone at its edge—probably medieval in origin. Barely three feet tall, it sits upon an overgrown arc of stones that curves around the hillock reaching down towards the well and was obviously a small building of some sort in previous centuries. Its precise nature is unknown, but it has been suggested to have either been an earlier well-house or surround, or perhaps the remains of a hermit’s cell—even St. Maha himself—that has fallen away over time. Without an excavation, we may never know what it was!

Whatever the origin behind the small standing stone and the overgrown scatter of rocks, one of our adventurers on the day we visited—little Leo—was fascinated by it, almost attaching himself to it and stroking his way round and round the old stone with playful endurance. And then, when he got to see the sacred spring below, became so taken by it that he simply sat down in the waters without as much as making a gasp, despite the cold! Aisha (his mum) would pick him up, only for him to walk right back over and sit himself right back into it again! It was both comical and fascinating to watch and he seemed quite at home in the pool, despite being drenched and cold. Indeed, he took exception to being lifted out of the water—and simply plonked himself back in it again!

Folklore

The Canmore website tells some intriguing folklore about the place, saying:

“The well is still a focus of local cult, and is visited by people who leave offerings in the water. A man dying recently in a local hospital refused to drink any water except water taken from this well.”

References:

- Edlin, Herbert L. (ed.), Queen Elizabeth Forest Park, HMSO: Edinburgh 1973.

- Johnston, James B., The Place-Names of Stirlingshire, R.S. Shearer 1904.

- Michell, John, The Earth Spirit: Its Ways, Shrines and Sanctuaries, Thames & Hudson: London 1975.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Nicholson, A. & Beaton, J.M., “Gaelic Place-Names and their Derivations,” in Edlin’s Queen Elizabeth Forest Park, HMSO: Edinburgh 1973.

- Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments Scotland, Stirling – volume 1, HMSO: Edinburgh 1963.

- Smith, H. Guthrie, Strathendrick and its Inhabitants from Early Times, James Maclehose: Glasgow 1896.

- Watson, W.J., The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland, Edinburgh 1926.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Aisha Domleo, Lara Domleo, Leo (the stone-hugger) Domleo, Unabel Gordon, Nina Harris, Paul Hornby and Naomi Ross for their help and attendance in finding and falling about this ancient sacred well. A damn good wet day all round!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian