Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 13265 45943

Also Known as:

- Carving no.322 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Carving no.157 (Hedges)

Take the directions to reach the Haystack Rock, then head onto the moor following the southeast footpath for a few hundred yards, towards where the moor slopes uphill. 20-30 yards before the uphill slope, a yard to the right of the path. It accompanies the Young Idol Stone with its two small cups, just a few yards away. Keep your eyes peeled and y’ can’t really miss it! If you hit the large slightly-pyramidal-shaped boulder with its well-worn lines running from its top (the Idol Rock), you’ve gone past it.

Archaeology & History

An intriguing carving this, and one which has always had me edging towards a manifest linear or logical myth underscoring its form. It’s the almost binary or primal numeric system in the lay-out of the cups which seems to do it. Few other carvings in the region exhibit this tendency.* If you aint seen it ‘in the flesh,’ check it out.

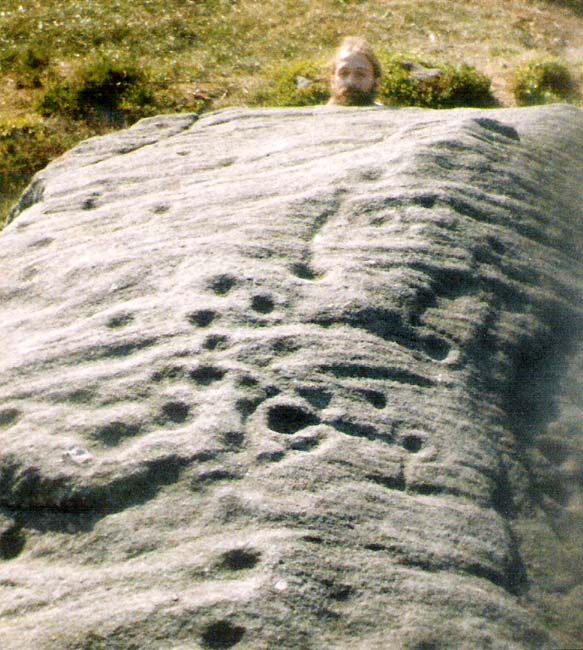

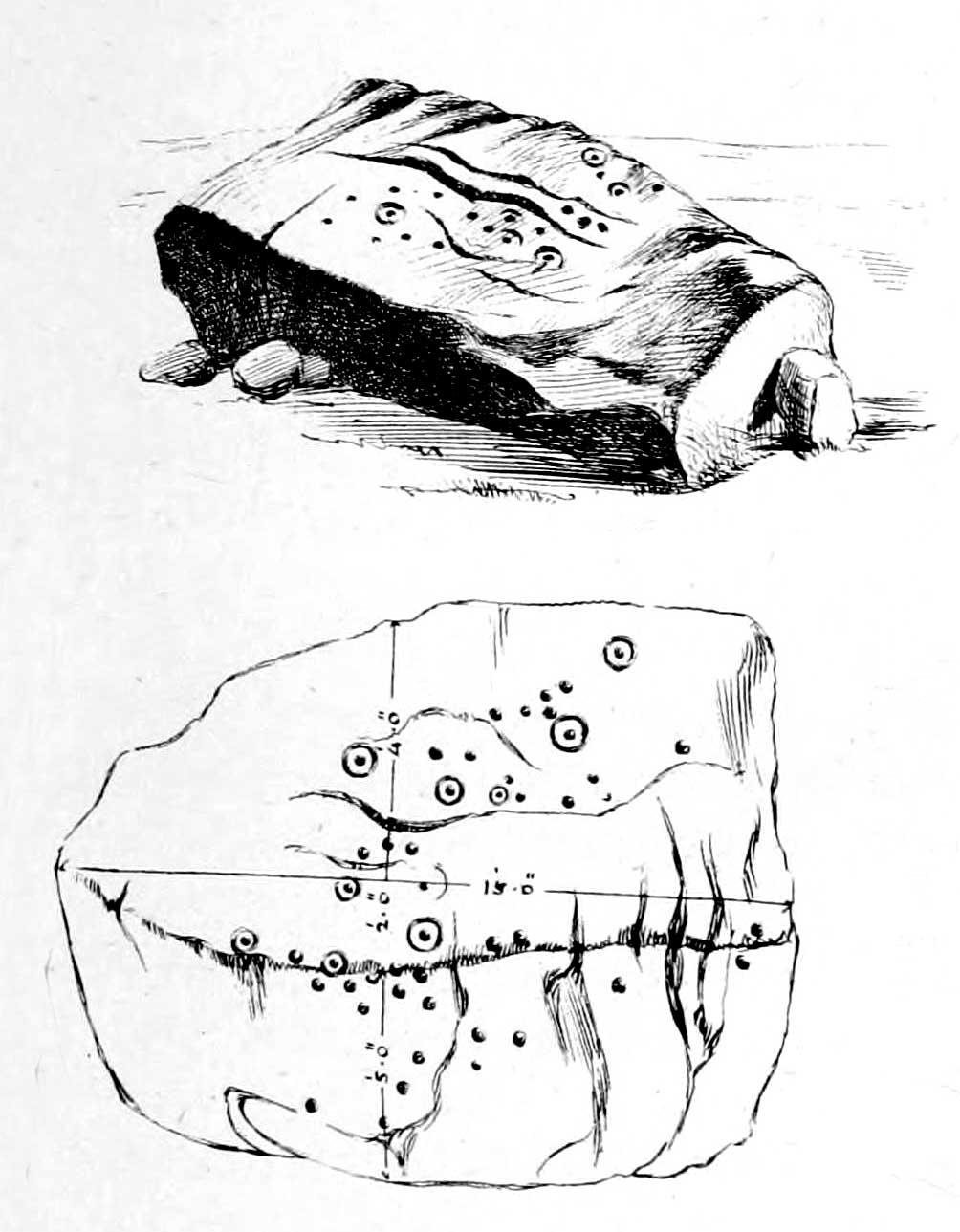

First described by that old Victorian J. Romilly Allen (1882), he seemed equally impressed by it, calling it “the most beautiful specimen of prehistoric sculpture,” continuing:

“The stone is of grit, and measure 3ft 2ins, by 2ft 6ins. Its upper surface is nearly horizontal, and has carved upon it cups varying in diameter from 2ins to 3ins. A row of cups in the middle of the stone are entirely surrounded by a groove. There is also a channel running round the outside. Single cups are often found encircled by one or more concentric rings; but it is very exceptional indeed to find several cups surrounded by a single groove, or to find the cups so symmetrically arranged as in the present instance.”

Prehistoric walling runs very close to this and the adjacent rock carvings, with the well-known ‘enclosure’ just a short distance to the east on the same moorland plain. This carving is very much on the edge of, or within, Green Crag Plain’s ‘Land of the Dead.’

This carving was one of several that Alan Davis (1983) measured in his exploratory survey on the validity of Alexander Thom’s ‘megalithic inch’ unit. This issue absolutely fascinated me as a boy, as it brought the attention of these curious non-linear images into the domain of mathematics and the higher sciences, instead of the lowly social sciences within whose domain archaeology is embedded, with its many inaccuracies and falsehoods. A number of astronomers and other academics did a great number of papers exploring potential units-of-length, surveying the carvings (and megalithic rings) in much greater detail than any previous archaeologist. Much of it was excellent work. However, the mythos of our ancient ancestors possessing great technical knowledge and mathematical ability was unfounded. In Davis’ (1983) paper — edited and expanded a few years later (1988) — he found no evidence of mathematical units of measurement here; though left the option ‘open’ for further discussion and analysis on several others, where multiple units of megalithic inches were measured. These findings however, are more likely the result of mere chance.

In 2011 some unnamed people visited the Idol Stone carving and vandalized it (this sadly happens more and more up here); but this form of vandalism is now being termed “twenty-first century informal unauthorised carvings” and is actually sanctioned by Ilkley Parish Council members, local businessman Tom Lonsdale and his affiliates as artistic “tradition”! Indeed, the damage done here and vandalism done on some other ancient carved stones that have been redesignated by Tom Lonsdale and friends as “twenty-first century informal unauthorised carvings”, legitimizes and encourages others to follow in their shallow-minded ignorance, enabling others to add their own form of ‘art’ on these supposedly protected monuments, on a region with an alleged SSSI status. They even encourage supposedly ‘nice’ people — y’ know the sort — to etch poems and such things onto the stones on the moors, in violation of regulations that apply to the general public. As a result, expect more vandalism — sorry…arty “twenty-first century informal unauthorised carvings” both here and elsewhere. This same appalling debacle — sorry, “tradition” — has been encouraged on the Haystack Rock, Hanging Stones and other prehistoric carvings on the moor.

Folklore

The name ‘Idol Stone’ was an invention of one of the Victorian romanticists, who saw heathen idolatry and perversion all over these moors (you’ve gotta ask y’self, what the hell were these people up to!?). Our old friend Nicholas Size (1934) told there to have been ghostly figures and druidic activities occurring at this site.

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, ‘Notice of Sculptured Rocks near Ilkley, with some Remarks on Rocking Stones,’ in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 38, 1882.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, West Yorkshire Archaeology Service 2003.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Davis, Alan, ‘The Metrology of Cup and Ring Carvings near Ilkley in Yorkshire,’ in Science and Archaeology, 25, 1983.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Hotham, John Paul, Halos and Horizons, Hotham Publishing: Leeds 2021.

- Jennings, Hargrave, Archaic Rock Inscriptions, A. Reader: London 1891.

- Size, Nicholas, The Haunted Moor, William Walker: Otley 1934.

- Speight, Harry, Upper Wharfedale, Elliott Stock: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian