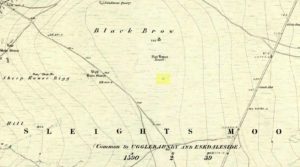

Legendary Rock: OS Grid Reference – TF 3127 6901

Also Known as:

-

Big Stone of Slash Lane

Archaeology & History

There is no specific archaeological information about this stone. However, we must take note of the so-called “devil’s footprint” that was on the boulder. In some parts of the UK, some devilish and other mythic footprints on stone are prehistoric cup-markings; but we have no idea whether this impression was such a carving or—more probably in this case—Nature’s handiwork. The field in which the stone existed was said to be the place where the so-called Battle of Winceby occurred.

Folklore

The stone was mentioned in several old tomes, with each one generally repeating the same familiar story, and with motifs that will be familiar to antiquarians and folklorists alike. In an early edition of Notes & Queries we were told of,

“the large stone in Winceby field, where soldiers had sharpened their swords before the battle. This was a stone of fearful interest, for much treasure was supposed to have been buried under it. Numerous attempts have been made to get at this treasure, but they were always defeated by some accident or piece of bad luck. On the last occasion, by ‘yokkin’ several horses to chains fastened round the stone, they nearly succeeded in pulling it over, when, in his excitement, one of the men uttered an oath, and the devil instantly appeared, and stamped on it with his foot. “Tha cheans all brok, tha osses fell, an’ tha stoan went back t’ its owd place solidder nur ivver; an’ if ya doan’t believe ya ma goa an’ look fur yer sen, an’ ya’ll see tha divvill’s fut mark like three kraws’ claws, a-top o’ tha stoan.’ It was firmly believed the lane was haunted, and that loud groans were often heard there.”

The tale was retold in Grange & Hudson’s (1891) essay on regional folklore. In Mr Walter’s (1904) excellent local history survey, there was an additional shape-shifting element to the story which, in more northern climes, is usually attributed to hare; but this was slightly different. The stone, as we’ve heard,

“was supposed to cover hidden treasure, and various attempts were made at different times to remove it, sometimes with six or even eight horses. At one of these attempts, his Satanic Majesty, having been invoked by the local title of ‘Old Lad’ appeared, it is said, in person, where upon the stone fell back, upsetting the horses. On another occasion a black mouse, probably the same Being incarnate in another form…ran over the gearing of the horses, with a similar result. Eventually, as a last resort, to break the spell, the boulder was buried, and now no trace of the boulder, black mouse, or Satan’s foot-print remains.”

Sadly we have no sketches of the devil’s ‘footprint’; and if local lore is right, we’ll never know. For tis said that a local farmer in the 1970s dug down and removed the stone completely. All that he found were numerous broken ploughshares around the rock, indicating that many tools had been used to shift the stone. In much more recent times however, a fellow antiquarian has said that it can still be found: so, if you can get a good photo of it, stick it on our Facebook group.

References:

- Grange, Ernest L. & Hudson, J.C. (eds.), Lincolnshire Notes and Queries – volume 2, W.K. Morton: Horncastle 1891.

- Gutch, Mrs & Peacock, Mabel, Examples of Printed Folklore Concerning Lincolnshire, David Nutt: London 1908.

- Walter, J. Conway, Records, Historical and Antiquarian of Parishes around Horncastle, W.K. Morton: Horncastle 1904.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks for use of the Ordnance Survey map in this site profile, reproduced with the kind permission of the National Library of Scotland.